Feedback Loop is a new column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City.

Over the last two months, New York City has hosted two film series centered around criticism written in the 1970s: Film at Lincoln Center’s “Never Look Away: Serge Daney’s Radical 1970s” and Anthology Film Archives’ “Afterimage: Counter Cinema, Radical Cinema.” These series’ titles notably both feature the word radical, identifying the films in them and the criticism they stem from as both inventive and politically direct. After all, these were films and this was criticism made in the aftermath of ‘68; it was filmmaking and writing determined to take both cultural forms in new directions.

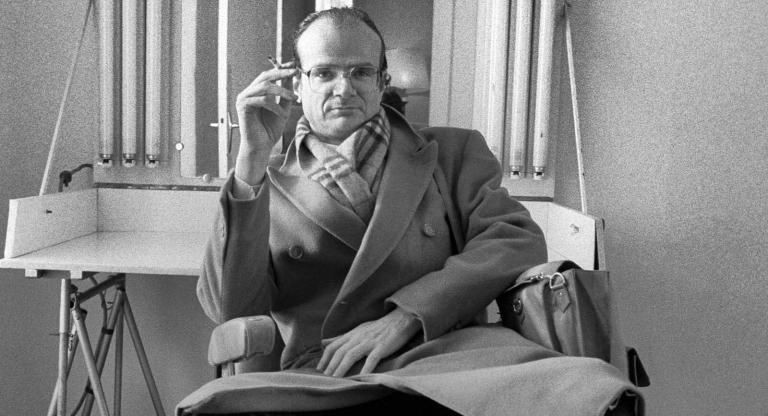

The series were occasioned by the release of two new books: Footlights, a collection of the French film critic Serge Daney’s essays throughout the ‘70s recently translated by Nicholas Elliott and released by Semiotext(e), and The Afterimage Reader, a comprehensive anthology of the eponymous independent British film journal published by The Visible Press. It is not atypical for the release of a new book to be accompanied by a film series, but it puzzled me that both of these series were taking place with such proximity to one another. There was an argument embedded in the title “Never Look Away,” and I had the feeling that these series were asking audiences to look back in order to think about what the future of film and criticism could be.

Looking back on the films I watched as part of these series—Blood of the Condor (1969), Milestones (1975), Numéro Deux (1975, pictured at top), Nationality: Immigrant (1976), Hitler: A Film from Germany (1977), The Devil, Probably (1977), The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (1978), Dog’s Dialogue (1979), From the Clouds to the Resistance (1979), and The Angel (1982)—it is obvious their assemblage represents a political argument. These films’ subjects—leftist (dis)organization, the aftereffects of World War II, the abuse of mass media—and styles—a mix of vérité and fiction, narrative proliferation, formal experimentation—embody a type of cinema committed to understanding its history, advocating for new modes of political organization, and pursuing new forms of artistic expression.

“The films that they showed and the political reasons behind them remind you of the reason for criticism in the first place—the reasons that critics like Daney were doing this at all,” said Michael Koresky, co-editor and co-founder of the publication Reverse Shot, in a conversation we shared over Zoom. “I think that the resurgent ideas around criticism and politics, especially in the last few years, have crystallized for a lot of young people—people who have grown up in a 21st century during which film criticism has been marginalized and pushed to the sides of the culture.”

As a writer who grew up during a period that the film critic Kent Jones characterized for its “marginalization of cinema,” it is clear to me that my contemporaries are dissatisfied with the diminishment of cinema’s role in culture. This is why they favor watching old movies instead of new ones. The sentiment does not arise from nostalgia, but from the feeling that films are not grappling with the difficulty of our moment with the same commitment filmmakers have demonstrated in the past. Looking back presents us with examples of films that believed in alternative visions for society, and remind us that there once were artists—and there still could be—who use the medium to challenge the status quo.

“We’re living in desperate times, and young people are looking for profound art, not in an escapist mode, but to cope with this challenging time,” surmised Elliott, who co-programmed “Never Look Away,” when I asked him about New York City’s repertory audience and their increased appetite for intellectually stimulating and politically direct cinema. Desperate times call for desperate measures, not for palliatives but solutions. “The intellectual or political valence of going to see a film has become more important because the gesture of going to the theater needs to find ways to move beyond the film itself,” said Maddie Whittle, Assistant Programmer at Film at Lincoln Center, who organized “Never Look Away” with Elliott.

Perhaps these sentiments, combined with the attention Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Hitler: A Film from Germany received from press outlets like The New York Times and Hell Gate, explain why Film at Lincoln Center was able to sell out their seven-hour screening of this challenging cinematic investigation into the despot’s image and legacy. This sold-out screening—which counted many young filmgoers in its audience—posits that challenging is in vogue, at least in New York City. It’s a strange phenomenon, especially in the context of a culture characterized by short attention spans, an addiction to bit audio-visual content, and a tendency to pass knee-jerk reactions off as criticism.

In the introduction to the latest issue of his film journal, Bombast, the film critic Nick Pinkerton writes, “After spending so much of my adult life attempting to make a living as a film professional of some kind, it began to seem like it would be more fun—for myself and for others—as well as more useful to be a film unprofessional. This didn’t mean slackening standards, but instead keeping standards up when so many of the extant outlets that paid for writing about cinema were encouraging a type of shallow, shirking, received-wisdom criticism that was inimical to a healthy film culture.” Demanding and perceptive thinkers have always existed outside institutional environments, but rumination in criticism has more countercultural weight to it now than ever before. When I asked film critics what type of criticism they’d like to read while conducting research for this piece, the word they kept using to describe their ideal was rigorous. “Rigorous feels like a forbidding word, but I feel like it’s tied to this belief about criticism meaning something more than, ‘I want to be the pull-quote on the poster,”’ said Chloe Lizotte, Deputy Editor of MUBI’s online publication Notebook. These days, rigor is radical.

I will not pretend Footlights and The Afterimage Reader are popular books, but I do think it is worth noting copies of each title sold rather well at Film at Lincoln Center and Anthology Film Archives respectively. “You know, we don't always make a lot of sales here on site because we're not really a bookstore, but this time… Yeah, it sold, for sure,” said Jed Rapfogel, Film Programmer at Anthology Film Archives. Meanwhile, Whittle reported that Footlights “sold out again and again.” These purchases bode well for film culture, not because they gesture at writing that will be influenced by the books’ contents, but because they are evidence of an audience willing to engage with rigorous criticism and films.

Thanks to Richard Brody, Nicholas Elliott, Michael Koresky, Chloe Lizotte, Jed Rapfogel, and Maddie Whittle.