In the 1959 L'An V de la Révolution Algérienne (A Dying Colonialism), Frantz Fanon writes about radio as a revolutionary technology. The use of various forms of communication and media in the context of liberation struggles is ongoing and transformative. It was displayed with renewed emphasis during Israel’s latest assault on Gaza, where the destruction of news offices and the longer history of suppressed journalistic coverage was overcome only by the self-documentation, across social media, of Palestinians living under occupation. A few years after the beginning of the Algerian War of Independence in 1954, Fanon described something similar: the role of the radio as a form of anti-colonial resistance. He wrote about the cultural imperialism of Radio-Alger, a French station which worked as an anchor for domination, part of the colonial power’s overwhelming monopoly of radio stations and virulent censorship of Algerians. The radio functioning as only a device of oppression shifted in 1956 when the nationalist Algerian political party, the Front de libération nationale (National Liberation Front), created their own radio station as a counter-voice. Capable of travelling more easily than print media, and not bound to the barrier of literacy, the radio enabled social transformation and political possibility, spreading anti-colonial militancy across the airwaves. As Fanon wrote, “In making of the radio a primary means of resisting the increasingly overwhelming psychological and military pressures of the occupant, Algerian society made an autonomous decision to embrace the new technique and thus tune itself in on the new signaling systems brought into being by the Revolution.”

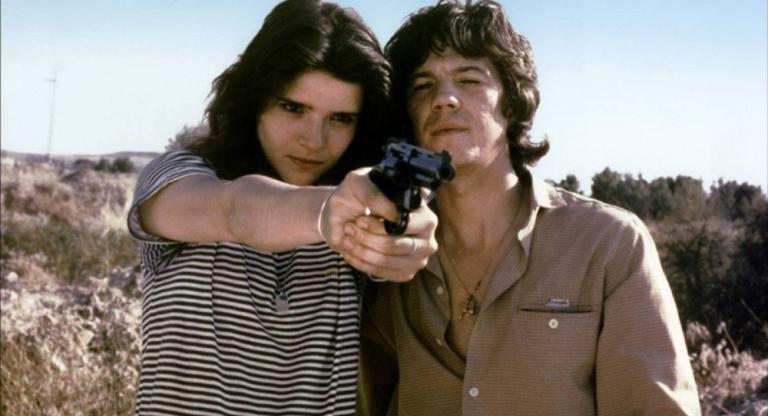

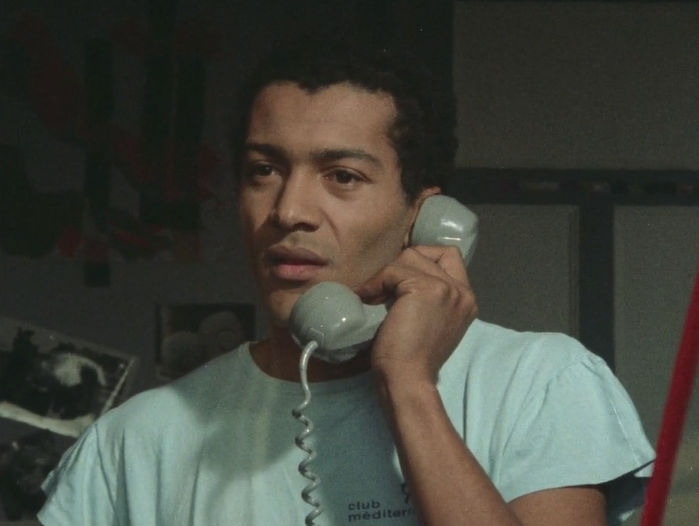

Set in Paris two decades later, Fanon’s fellow Martinican Julius-Amédée Laou’s 1983 short film Solitaire à micro ouvert (Open Mic Solitaire) also invites a meditation on the function of the radio for formerly and continuously colonized peoples. Born in Paris, Laou is also a playwright, and his theatrical credentials inform the particular construction of space in the film. This concentrated cinematic exercise follows Mathieu Sainte-Lucie (Serge Ubrette), who takes a black radio station hostage after his brother is murdered off-screen in a racist attack by a far-right group. Accompanied by his white girlfriend Karine (Marilyn Canto), Mathieu rushes out of their apartment when someone calls with the news, with the image ominously shifting from its initial bruised color palette to black-and-white. The shots of them speeding through Paris on a motorcycle on their way to the morgue recalls a similar image in Afrique-sur-Seine, the 1955 short by Beninese-Senegalese film director, historian, and theorist Paulin Soumanou Vieyra. Cited as the first film by a Black African and concerned with the experience of Africans living in Paris, it features what was sometimes referred to as “couple domino” (black/white couple) zipping along on a moped. Intentionally or not, this creates a lovely sense of a Black cinematic tradition citing itself.

Black internationalism, displacement, diasporic communities, political apathy, performances of militancy, the condition of being Black and French are all operative in the compressed 18 minutes of Laou’s film. His work is also framed by its position within Caribbean Cinema. The APDCC (Association for the Promotion and Development of Caribbean Cinema), which was founded in 1985 by two Martinican women, Suzy Landau and Viviane Duvigneau, showed this film and two others by Laou in a program called “Regards sur l’Emigration.” For Third World filmmakers living and working in First World metropolises, the tensions of emigration and exile were and remain critical.Similar to the works of Med Hondo, the Mauritanian filmmaker exiled in France, Laou’s Solitaire à micro ouvert (Open Mic Solitaire) presents a complex re-consideration of the classifications of Black Cinema, the porous boundaries between national and diasporic cultural production and how media can be mobilised towards recuperating relationality. Taking up the majority of the short is a stunning formal flourish which presents a series of shots of people listening to Mathieu’s radio address: a man sitting alone on his couch with a newspaper and drink; a couple smoking in their car; a crowded café; a group of young people hanging out outside, sitting on the hood of a car and lounging on the sidewalk. Laou deftly yokes these spaces through the sonic continuity of Mathieu’s words. His voice is de-corporealized and made mobile and transmissible, refuting the colonial enclosures that form an obstacle to the potential for Black solidarity. The radio is activated as a technology for generating interconnection and new forms of belonging for the displaced, the exiled, and those forced into currents of migration dictated by the predatory exigencies of former colonial powers and the Global North.

Solitaire à micro ouvert is currently playing as part of the Media City Film Festival’s THOUSANDSUNS CINEMA program, free online until June 24. Its selection was curated by Steve Macfarlane.

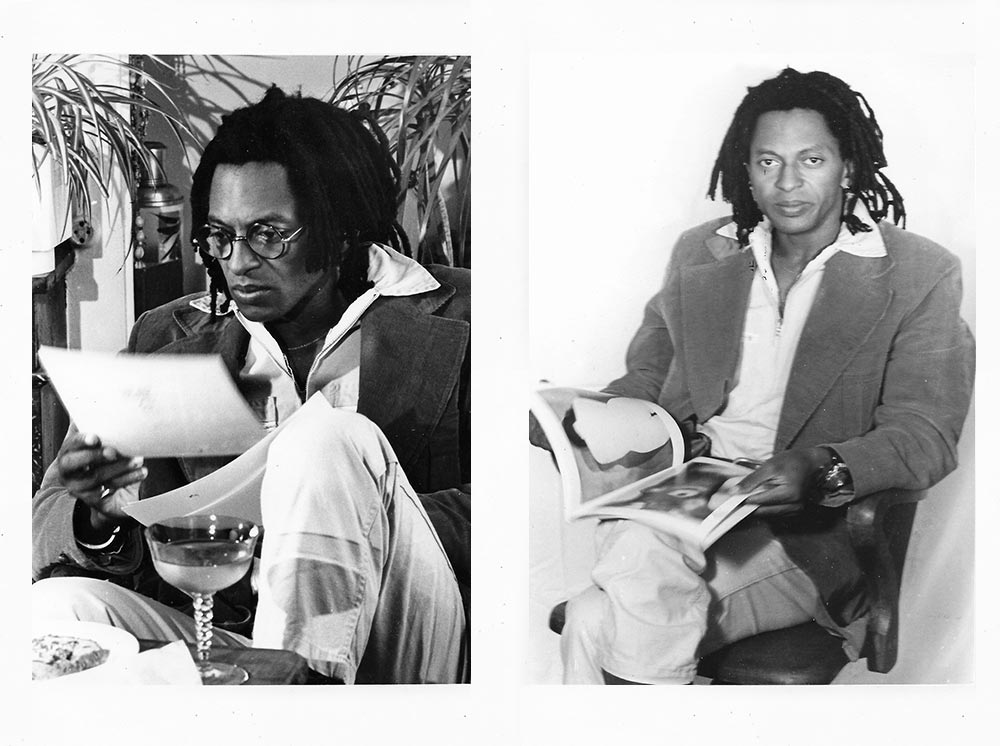

Laou currently lives in Montpellier, France. In late February I had the pleasure of having a long phone conversation with him, in which we spoke about the political convictions of his film, drawing on long histories of anti-colonialism, and his work across film and theatre. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Yasmina Price: I’ve been looking forward to speaking with you ever since Steve sent me the link to your film. It’s a fascinating, heterogenous piece and I immediately thought: why have I never heard of this filmmaker?

Julius-Amédée Laou: There are far too many very good films and excellent black filmmakers who are unknown because we are very widely and deliberately marginalized by the system.

Regrettably common for Black filmmakers. So I would like to start with how you came to cinema. I know that your primary sphere is theater.

Well, I would have liked it to be cinema, but when you are Black and come from the working class, the path is blocked, because the film industry has such a financial barrier to entry. At the beginning I did theatre, I wrote plays. I also have a company. I came to cinema completely by accident. What you saw is my first film, a short. The starting point was the desire for a particular actor to be in one of my plays. He had approached me by saying, “Hey, Julius, there’s this competition organized by the Centre National [CNC, Centre National du Cinéma et de l'Image Animée].” And I thought well, let’s do it, and I wrote a screenplay. I’ll gloss over the details or else we’ll be here for too long.

These details are the most interesting parts of history.

All right, I’ll paint a little picture: the last day for the screenplay submissions for the year was a Friday at 4:00 pm, and I don’t know what happened but I arrived at the address at 4:20 pm. The administrative aide who oversaw receiving the documents was closing the door and about to leave. I apologized and explained I have been struck in traffic. And she said, “No, no. It’s over.” And I then spoke to her for a quarter of an hour and managed to convince her.

Well, that’s certainly a bit theatrical. Sounds like you chatted her up and it worked.

Yes, it worked. She re-opened the door, went back to her office, and submitted my screenplay. There were hundreds of entries, between 700 and 800. I was the last admission and yet ended up being one of the 3 chosen, which meant you received financing to make a short film.

Was the subject of the screenplay something you’d had in mind before?

I had a friend whose little cousin was murdered by a racist group, skinheads. They had kidnapped and killed him and what had shocked me is that the parents didn’t report it.

They would have little reason to trust the police.

Black people in France couldn’t trust French police. They have always been racist murderers of young Black men in France. Around that time there was also a young black man, a Martinican, who had been killed in the street by the police. There was a protest and they fired into the crowd. And what shocked me here was that there was no protest, no reaction afterwards. Nothing at all because he was Black. And this passivity outraged me. Which is why it brings me such joy to see all these protests and rebellions now. And of course, we have to make the connection to [Adama] Traoré [a 24-year-old Malian French citizen who died in police custody in 2016 in Beaumont-sur-Oise. His sister, Assa Traoré, has since relentlessly organized against police violence in France].

Absolutely, it’s the same ongoing structure of violence.

We must defend the memory of Adama Traoré. A majority of white French people accuse us of being divisive. But at least now there are reactions. It brings warmth to my heart. People used to say nothing, especially if the perpetrators were cops. One remarkable example was in 1967. There was a series of protests in Guadeloupe. [Sometimes referred to as May ’67, a strike by construction workers in Pointe-à-Pitre, which led to further protests that were met with a massacre by the police. The episode is a horrific entanglement of Guadeloupe’s status as a French colony, bound up with a suppression of racialized labor and state control.] The police murdered a few hundred people. Even today families are scared to talk about what happened to their loved ones killed during this massacre in 1967. It was terror. They assassinated people in the streets like they did in Algeria. There are witnesses. This is the context that pushed me to write this story.

The film is a cry of protest, of revolt, of refusal towards the State. I see this as part of a longer lineage of African, anti-colonial, revolutionary cinema.

There are the things which give it a shape. It is because one is anti-colonial and pan-Africanist that one makes films. Our sensibilities, our visions, of course exist in all expressive forms. In writing as well as in cinema.

And theater.

In my plays I talk essentially of the small and also the great history of the Black people.

Neither is most of what we call history.

I knew my great grandmother and when I was little, she would tell me stories that her parents had told her about slavery. So I have a personal, direct connection to slavery, with a people who are part of tragedy that is ongoing.

It’s elastic, it keeps extending. And the particular crisis of this film, the foundational violence of policing towards Black people, it’s constant — in Paris, in New York, in Lagos.

A difficult reality, always.

A point of curiosity: you’ve worked with Jean Rouch? I always think of what Ousmane Sembène said in that conversation between them, that white Africanists and ethnographers look at Africans like insects.

Well, Jean Rouch was on the jury, and he was the one who was decisive in choosing my screenplay. He was a man overflowing with enthusiasm, extraordinarily energetic. Out of gratitude to him, I will not allow myself to say bad things about him.

Right, in Folie Ordinaire d’une Fille de Cham, you drew on your theatrical training for a work of cinema. Returning to the source.

The director of my play Folie Ordinaire d’une Fille de Cham, Daniel Mesguich, did a beautiful job. It’s my play which had the most success. It was translated in multiple languages and toured in England, Germany, Sweden. It travelled around with the same company from 1984 to 1999.

Did you often work with this same troupe? Theater seems to activate certain possibilities for collaboration that are perhaps more difficult in certain hierarchal habits of filmmaking.

Yes, more or less the same group. But I stopped a few years ago, and now with COVID…

I asked the question thinking about Sarah Maldoror and Med Hondo, who both started in theater.

There’s the obvious point that film is prohibitively expensive, and you barely need anything to put on a play.

Another ongoing problem.

Problems from the start. There were so few black actors, filmmakers in the 1980s. And my film is polemical. I thought to myself “you’re going to get in trouble.”

I was looking at the list of actors you’ve worked with. I recognized a few of the names, like Jean-Michel Martial and Alex Descas.

Yes, they both started out with me in theater with my play Ne M’Appelez Jamais Nègre! There are quite a few actors that people now know who started out with my troupe, La Compagnie des Griots d'Aujourd'hui.

A lovely testament to the importance of having alternative cultural structures.

Yes, when I started writing my first play I was in Senegal, where I stayed for two years.

Diasporic stories. Incredible how so much hasn’t changed both on the continent and in the diaspora.

It’s true, the rulers of the world refuse change at all costs.

Absolutely, the empire endures. But there have been and there are now forms of international solidarity.

Yes, and it warms by heart. I remember being young in the 1960s and 1970s, and the work of the Black Panther Party. I used to meet a lot of friends through similar work, up through the end of the 1970s. There were also white hippies and leftists. But I would be shocked when they said [referring to Black militants] “If they want to take up arms then they deserve to be stopped.” Young people were afraid of real solidarity! This was a fight for justice, and they took it as a personal offence.

Conditional solidarity also continues. If it’s alright, I’ll turn back to a question about the film. The soundtrack is stunning!

Yes, it is beautiful music. It was made especially for the film. It’s funny, the person who did it, I knew him in elementary school. We’d lost track of each and then I was looking at this whole list of musicians for the film and happened to pick him, without even realizing.

And you made a few more films afterwards?

Yes, three. Mélodies de Brumes à Paris (1985) is about an Antillean man living in Paris. He goes to war in Algeria and returns traumatized. He’s badly off, he has hallucinations, he can’t reintegrate into society. My grandfathers came to France from Martinique to fight for France in the war of 1914-1918. And I also wanted to talk about my uncles who fought in the Indochina War and the Algerian War for France, so I told the story of my family in an artistic adaptation. La Vieille Quimboiseuse et le Majordome (1987), I really like this film, about an old Martinican couple and through the entire film they just tell their story. They both do housework, and the woman wants to stop doing that to become a dancer, like Josephine Baker. And her husband is fine staying a butler. She reproaches him for his servility. Then she admits she had an affair with their boss when they were servants in the same house. Anyway, it’s about their story as they take a long walk through Paris.

Well, I certainly hope the rest of your films are screened soon.

I very much hope so too. Thank you!