Few writers have mapped the terrain of American film and culture with the same breadth and acuity as J. Hoberman. Over a career spanning more than four decades, the longtime Village Voice critic—on staff from the early 1970s, and senior film critic from 1988 to 2012—has brought his sharp eye and expansive knowledge to everything from underground cinema and Cold War pop culture to the outer edges of mass media.

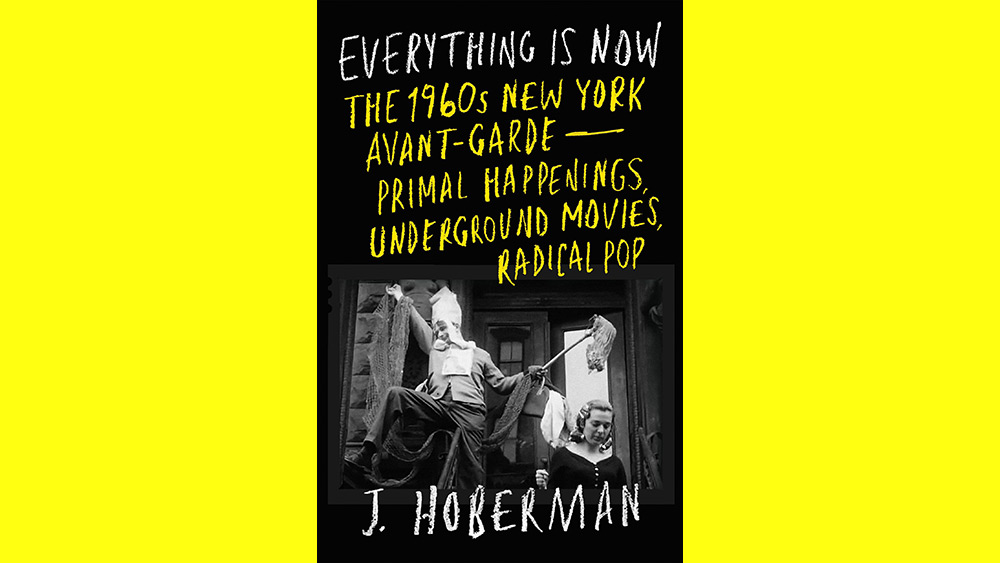

His latest book, Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde, draws on a lifetime of immersion in experimental film, performance, and art to trace the electric crosscurrents of a New York moment when cinema, music, visual art, and radical politics collided in unprecedented ways. Meticulous, yet deeply readable, Everything Is Now foregrounds iconic figures like Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, and Jack Smith, alongside the forgotten venues, marginal personalities, and ephemeral happenings that animated this vibrant scene.

I spoke with Hoberman about the making of the book, the films he selected for his accompanying series at the Anthology Film Archives, and what the 1960s avant-garde still has to teach us.

Paul Attard: At what point did you realize that all this material you’d been researching and caring about over the years needed to take the shape of a book?

J. Hoberman: After I finished the “found illusions” trilogy [The Dream Life, Make My Day, and An Army of Phantoms], I really didn’t want to do another book on Hollywood movies. I’d done what I wanted to do, and I didn’t particularly want to write another film book. This is material I had been thinking about for 50 years, and I had considered various ways of approaching it before.

At one point, I thought about doing a book with 12 chapters on 12 different artists. But I decided that I wanted to focus less on individuals—though, of course, they’re still in there—and more on the city itself as the scene. I felt very close to the project, though I didn’t get a tremendous amount of encouragement to write it.

PA: Really?

JH: No. I’m very gratified by the reviews it’s getting now, but at the time it seemed surprising to some people, or maybe I just didn’t do a good enough job explaining exactly what I wanted to do. In any case, it all worked out and I’m very happy with it.

PA: I’m curious about what the process looked like and what the general timeline was once you really started to focus on researching this book. You’re not just sticking to one discipline and there’s a lot of dense information presented, in very readable fashion, throughout the book. How did this all take shape?

JH: There were some things I knew very well. For example, even as far back as Midnight Movies, my first book, I wrote the chapter on the underground, so I was able to draw on that. And I’ve written fairly extensively on Jack Smith and other things that I was able to incorporate.

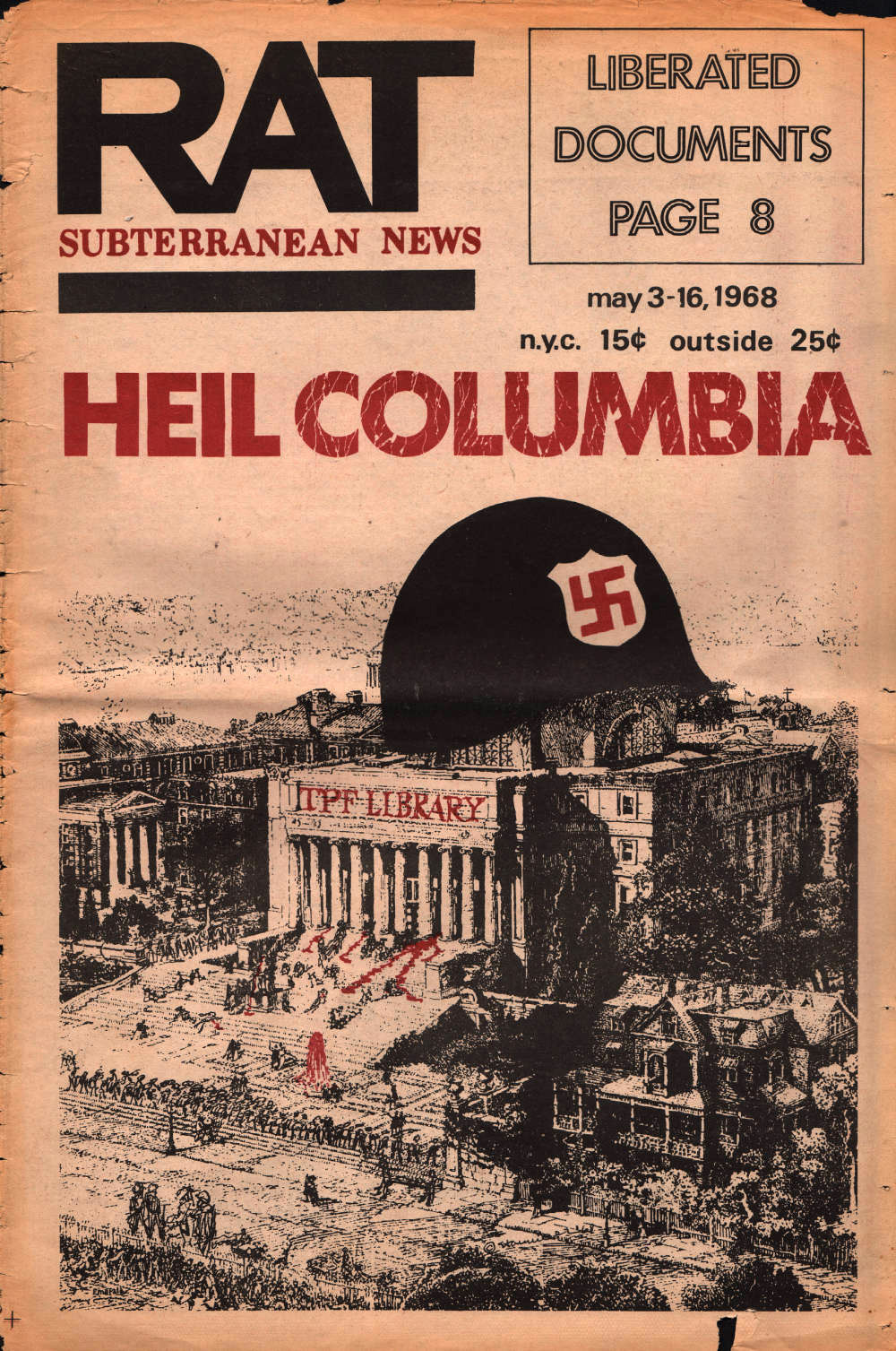

The first thing I did was to go through every issue of The Village Voice from late 1958 to 1972, and to take notes on what was in it to start work on a chronology. And there were other alternative newspapers that I looked at: The East Village Other in late ’65 and Rat in early ’68. I saw as many of those as I could, using the microfilm room at Butler [Library at Columbia University]. I was often the only person there using those microfilm readers. I was sort of surprised, but it was okay because when I wanted to use it, I could use it.

Then I began talking to people. There were maybe a dozen people I spoke with at length, and I did other interviews. And one thing would lead to another. I had a general idea of what I wanted to cover, but certain things would emerge from the research. There were a lot of things I had never heard of that I came across. I’m thinking of Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite. I was kind of aware of it, but I had no idea about its significance or how it happened. Similarly, I didn’t expect Amiri Baraka to be such a constant figure in this book. Robert Kramer’s films I had never thought about particularly before I started working on this. These things would present themselves as I was doing research. And, in effect, I would go down certain rabbit holes and learn about certain things.

Everything about the internet cuts two ways. I say I ended up doing this book paragraph by paragraph, because I would be curious about something and it’s so easy to start rummaging around online to see what you can find—although a lot of the material is not online. In terms of my personal process, it’s very important for me to make a chronology. I really have to work from that, to get a chronological sense of how things happened. That’s a way of mastering the material. But I don’t write chronologically at all, even within the chapter. So, it sort of came together—I don’t know, not to get all pretentious—like a painting.

PA: In Everything Is Now’s introduction you note that you consider the book to be many things, one of them being a “map.” You meticulously note the location of events throughout. Why was that important to you?

JH: I’m a lifelong New Yorker. Just walking around the city, downtown particularly, it’s always amazing to see what’s there and what’s not there—the things that disappear. At the same time, one of my daughters lives in Paris, so I’ve been there a lot. They are so aware of their landmarks. It’s not just naming streets after writers and poets, they’ll mark the buildings and so on. You couldn’t do that in New York. That will never happen here.

It was important for me to take note of that. When I submitted the manuscript to the publisher, I wasn’t sure if they would object to that or not, because it is kind of an eccentric thing to do. But it didn’t bother them. If there had been the resources, I would have put in a map, but they [the reader] can construct one mentally from the information provided.

PA: The way you’re able to hyperlink one person to another—sometimes from practically across the street—reminded me a bit of Robert Altman’s Nashville [1975].

JH: [Laughs] It’s funny to think of this now, but this goes back to the late ’90s when I was working on researching Jack Smith. When I first saw it [Flaming Creatures, 1963], I thought to myself, “Where did he shoot this?” I mean, it’s impossible to tell. I basically had to discover for myself that it had been shot on a rooftop—where it was, how it was shot—and then I was lucky enough to be given these on-site photographs that I later published in a monograph. And that’s just one rather extreme example of wanting to understand the physical location of something, but I would apply that to a lot of things. I was genuinely curious: where was Ron Rice’s loft? So I was grateful to be able to keep all of this in.

PA: We’ve already invoked two filmmakers you’re very familiar with—Jack Smith and Ron Rice—and I carry the mantra that you never watch an experimental film merely once. I imagine you rewatched a lot of other films close to you for this project. Did any of them change for you on rewatch this time around? Were there any films you saw for the first time or discovered?

JH: There were a couple of films that I discovered. Doomshow [1964] is one, by Ray Wisniewski.

PA: An anti-nuclear activist!

JH: Yes, an activist—not primarily a filmmaker—and it was about a group show put together by Boris Lurie and his friends. That was fascinating for a number of reasons. Then, Jonas Mekas’s version of The Brig [1964]. I came to realize that’s his most important film, which is not something I would have thought before I began working on the book. But I was very familiar with a lot of the films, so I didn’t revisit them all that much. Flower Thief [1960] and Senseless [1962], yes, but I hadn’t seen those in a while.

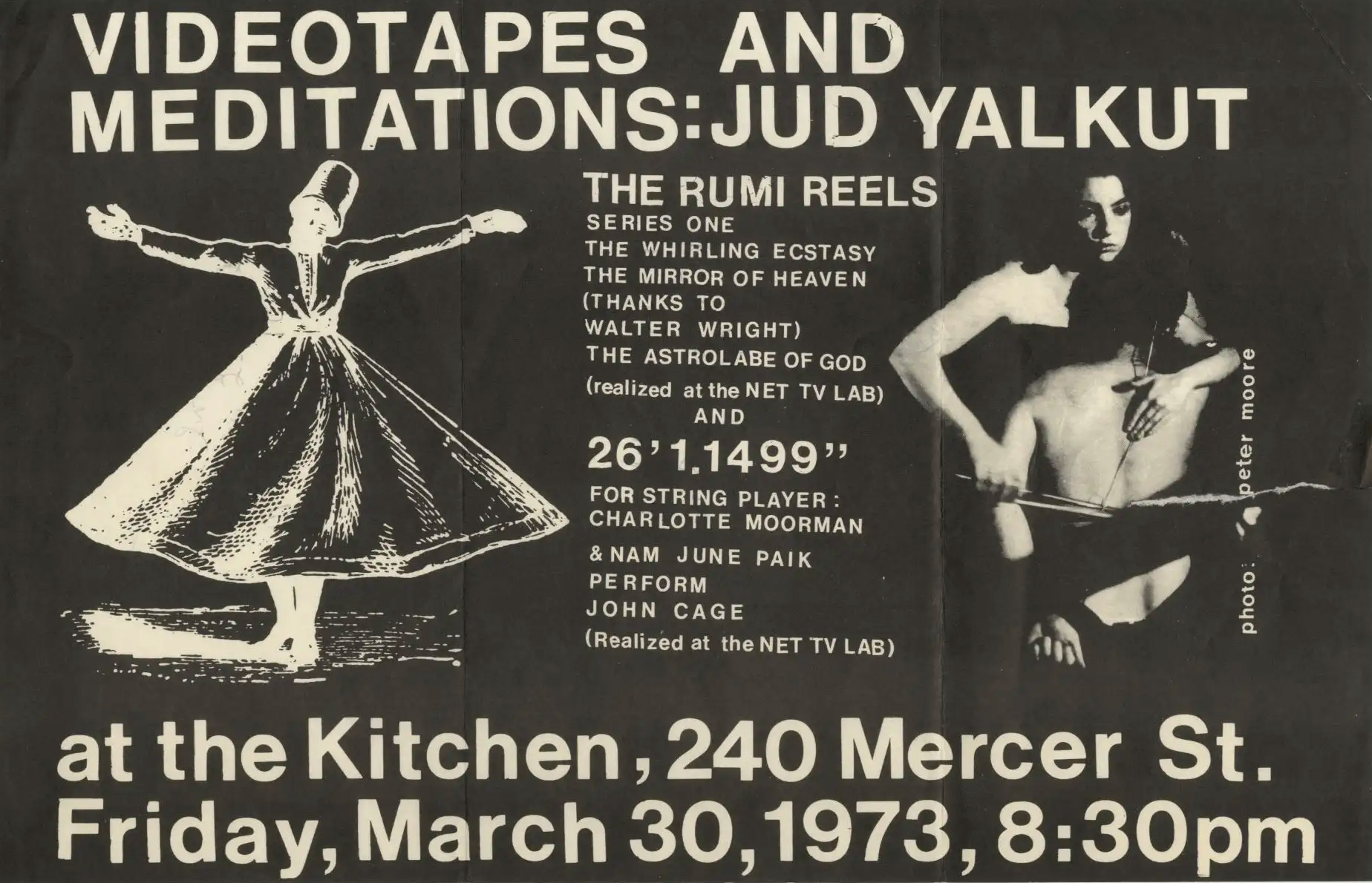

There were other things, like films by Jud Yalkut, who wasn’t really known as a filmmaker but was a significant documentarian of the scene. Videotape didn’t really come into use until the late ‘60s, and even then it was still kind of clunky. So 16mm was what there was for recording certain things. The one he’s probably best known for is the film he made about [Yayoi] Kusama [Self-Obliteration, 1968] which actually won some awards at the time and was fairly well-known. That’s not a film I would say I rediscovered, but its significance became more apparent to me as I was working on this.

There were also little films he made, like D.M.T. [1966], which draws on the work of an artist named Jackie Cassen, who is one of these kind of Zelig-like, unknown figures I became interested in while writing the book. Even in the mid-‘60s, the scene wasn’t that large—and geographically, it was somewhat compact. She was somebody who started as a gallery artist, working with Aldo Tambellini and that group, and then got really interested in light shows. She actually predates Warhol and lent him her slide projector for the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

Anyway, Yalkut made a little movie based on one of her pieces, which is named after an intense hallucinogenic drug—I think an LSD trip could last five or six hours, this was more like five or 10 minutes. That was a movie that had been sitting on the Film-Makers’ Co-op’s shelf for decades, I think, before I asked to take a look at it. It’s a great little film. That’s the kind of thing I just mention in passing in the book, but I was very keen on showing it in the Anthology series.

PA: You just observed that Yalkut wasn’t primarily known as a filmmaker, but you’ve programmed five of his films for the series. Was that intentional—to highlight more of his film work—or did it come about naturally as you started curating?

JH: The thing with the series is that I didn’t want to just show the canonical works of the period. I mean, Anthology already does that. What I did want to show, insofar as it was possible, was the degree to which these films were interstitial; in other words, how they manifested in and connected with other forms that were going on at the time.

And Yalkut—who, I should say again, I was aware of as a filmmaker, but just wasn’t that interested in since he didn’t seem to be working with film as film the way [Stan] Brakhage or Michael Snow or Ernie Gehr were—as I started researching, was there, documenting things, immersed in the scene, and doing it pretty well. The reason there are so many of his films in the series is because he was actually present. He was there, recording things and a lot of stuff from the ’60s was essentially ephemeral. The films are often the major documents. Performances weren’t regularly documented. Carolee Schneemann had a film made of Meat Joy [1964], which we’re also showing. Not because it’s such a significant film, but because it’s a significant documentation of a significant event. Once video became popular, it was no longer so surprising, since everything could be recorded one way or another. In the ‘60s, that wasn’t the case.

PA: Speaking of doing things a little differently, I was honestly surprised to see The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse, Part I: Huge Pupils [1968] included in the lineup. In your obituary for Andrew Noren, you mention that he issued a cease-and-desist against Anthology back in 2004 to prevent them from screening the film in their Essential Cinema series.

I’m curious about your perspective on showing works whose creators didn’t want seen, especially since you’re pairing this film with Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth [1964]. How do you approach including these kinds of films in the program?

JH: Well, I didn’t have to look hard to find them. Anthology had a print of the film. It’s perfect to show alongside Rubin’s film. She left her films to Jonas Mekas to do with as he wished, but out of respect for her, he didn’t show Christmas on Earth until after she died. So there’s a certain parallel there.

I’m very pleased with that program overall. I also think Noren hasn’t gotten the recognition he deserves. He destroyed many of his earlier films, which is frustrating. His later work is strong too, but to me this is the best of the diary films. I saw it when it was still called Kodak Ghost Poems. And the book is concerned with people breaking different laws and various taboos, so I think it’s really good to show his work.

PA: I completely agree with you on both fronts: that Noren’s work is underseen, and that this is easily one of the better diary films. But, to your point about these films breaking taboos, are you ever worried that, stripped of historical context, a work like this one won’t land as strongly?

JH: I don’t know. The only real response is through writing. I’ll be introducing all the screenings at Anthology, so there’s that. Beyond that, people will see what they see. I’ve had plenty of experience showing Flaming Creatures to both students and audiences, and some people get it and some people don’t.

One of the most memorable screenings I can think of was at the New York Film Festival, where it was paired with a film by John Greyson. His film—can’t remember the title—was very well-made, in conventional terms. And when Flaming Creatures was shown, even people who had known Jack Smith were outraged. They thought it was the worst thing ever. They didn’t get it at all. I’ve come to realize that the film’s great transgression is no longer the nudity, but how it was made. The “bad” filmmaking is what’s appalling.

PA: The poor-quality film stock, the lack of cohesion in the narrative, the refusal to follow any conventional filmmaking rules.

JH: Exactly. Some people pick up on that, and some don’t. A few years ago, I gave some talks on Jack Smith at CalArts, and it was really difficult for some students to understand how this guy could be so famous now, and yet have had such a—if not tragic, at least kind of miserable—career. I mean, he didn’t really make it in the art world. So I think the ambitions of someone like Andrew Noren, or Barbara Rubin, or even Ron Rice, might seem kind of alien to them. And maybe that’s the larger question: can people today grasp what these filmmakers wanted to do and what they accomplished? I’ll certainly try my best. And I do think the audience at Anthology will be the most receptive to this kind of work.

PA: Are there any films you wanted to show but for whatever reason couldn’t?

JH: There were certainly things I allude to in the book, like The Sky Socialist [1968] and Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man [1963], that would have made sense. But I recognized there was a finite number of films I could show, and I wanted to cram things in.

What I couldn’t get were the Warhol films, as they’re now very difficult to get. I would have wanted to show, for example, Poor Little Rich Girl [1965], but there was no way to show that. That would have been one. I don’t talk about Sins of the Fleshapoids [1965] that much in the book, but that could have been an option. I could have shown other early Ken Jacobs films, but I just wanted to show Blonde Cobra [1963], because to me that was such a radical use of found material, and I liked the way it worked with the other films on the bill. But a lot of Ken’s work could have worked.

PA: To return to something you said a little earlier: how is The Brig Mekas’s most important film?

JH: First of all, it’s his most successfully realized film. You have to put the diaries aside, but even there, he shaped them. So there’s that. I think that, conceptually, it was brilliant. One could also say that The Brig was the most significant of The Living Theatre’s productions, more so than The Connection [1961] because of how close to pure theatre it was.

Jonas filmed it like a documentary and then asked his brother to edit it—who had never seen the play—so he’s just dealing with what he’s got. It really is a documentary, in a way. The play is kind of related to a Happening, a very primal form of theatre. But the movie is something other than just a recording of the play. I like the fact that it’s an abrasive, confrontational work, which the play certainly was, and he [Mekas] conveys that well in the film. So I don’t think it gets the full respect that it’s due in his oeuvre.

PA: Since you mentioned The Connection, I feel inclined to bring up Shirley Clarke, who’s certainly another figure represented in the series who hasn’t really gotten her due.

JH: Not at all.

PA: She was one of the co-founders of the Film-Makers’ Co-op and isn’t featured in Essential Cinema, where the only other women included are Maya Deren, Marie Menken, Helen Levitt, and Leni Riefenstahl. Jonas later apologized for that omission.

JH: Well, it’s complicated. She had every reason to be upset on a personal level, because she was a generous person and very supportive of other filmmakers. And she made a different kind of movie. Jonas really went all out for The Connection, which I think had some strategy to it. There was always a certain amount of strategy in whatever Jonas chose to support. Brakhage and Sitney, and the more formally minded guys, would say, “We need to have Triumph of the Will [1935], but not this.” [Laughs]

I happen to think The Cool World [1963] is her best film, which is why I wanted to show it. And I think she got a raw deal from Frederick Wiseman too, who produced the film and then suddenly turned on her. He said, “Oh, I could direct better than that,” and really lost it. So I’m glad to have an opportunity to show it. She was one of the few downtown artists who really had a feel for this kind of material. She actually shot it on location in Harlem. She used non-actors. It’s a really gritty film. It has a good score. It has a lot of things I like. Portrait of Jason [1967] would have taken up too much space, but if it had been a more Warhol-heavy show, I would have shown it.

PA: You note that the alt-weeklies you read during your research are some of the only remaining documentation of a lot of performances and other Happenings. Speaking for myself, when I try to find information on certain experimental films, I’m lucky to even find a blurb in the Chicago Reader or elsewhere.

JH: The book really couldn’t have been written without the alternative press. You could say that if the subject of the book is New York at a particular moment, the medium is the press. It’s essentially how it was written about and processed by these writers, who were also breaking rules of decorum and so on.

I saw my strategy being, in large part, journalistic, less so than critical. I’m not doing a deep dive into the making of The Flower Thief, I’m talking about how it came into existence, how people saw it, and the impact that it had. Somebody else can do the qualitative analysis.

J. Hoberman Selects: Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde runs June 20-24 at Anthology Film Archives. Hoberman will be in attendance to introduce each program in the series. His new book is now available here.