Most of Nathan Silver's films involve his mother, Cindy Silver, who is both a central performer in his films and a consistent muse across decades of semi-improvised fiction and nonfiction projects. Many of his works circle around the broader idea of mothering—between unlikely cohabitants and ad-hoc communities, in addition to biological families—and many of his films are intertwined, with offshoot projects picking up stray threads from prior works and letting them pull him and his band of collaborators into intimate, highly-uncertain situations where life, barely reined-in, can unfold.

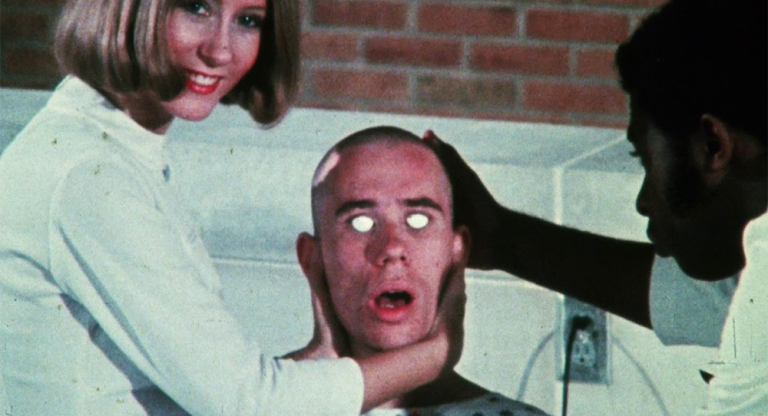

Take his latest, the short documentary Carol & Joy (2025), about national treasure Carol Kane and her 98-year-old mother Joy. In 2016, while editing Actor Martinez, Nathan decided to cut his mother’s scene from the film, much to Cindy’s anger and disappointment. He explored her feelings about that omission, and her larger unsettled relationship to being an artist (Cindy Silver got pregnant at 16, a story Nathan pursued in 2014’s Uncertain Terms, forcing her to give up hopes for a dance career), in his documentary series Cutting My Mother (2019). While filming, he was surprised to find out, on-camera at a synagogue, that his mother had decided to become a bat mitzvah in her 60s. (“I heard you say B’nei… I don’t know these things!” Nathan confessed to his mom.) That became part of the impetus for 2024’s Between the Temples, in which Carol Kane plays an adult bat mitzvah student receiving instruction from Jason Schwartzman, a young cantor in mourning. Carol Kane has described recognizing her own mother, piano and voice teacher Joy Kane, in Nathan’s description of her character while they developed the film.

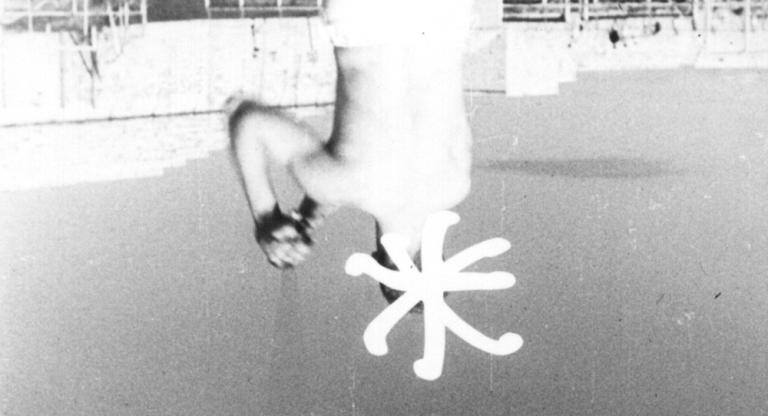

After they wrapped Between the Temples, Silver decamped to Carol and Joy’s shared apartment on the Upper West Side to film the pair’s relationship, and Joy’s own telling of her life story. Carol & Joy takes place over a single afternoon in their sunny and cramped quarters, where Joy meanderingly tells stories both difficult and triumphant from her childhood as a second-generation Jewish immigrant in Ohio, her young adulthood as a thwarted dancer, a stifling marriage that resulted in two children, an abortion, divorce, and at age 55, at last, a thrilling escape to live on her own in Paris. Throughout, Joy’s music students come in and out to rehearse, and visitors join the conversation on the couch. Joy is frank and open about the violence that domesticity and motherhood imposes, and how close to the brink she was. Carol prompts her mother through some of the more difficult recollections. When the film intercuts a black-and-white photograph of a grinning Joy seated with a drink at a bar in France, it is a triumph.

Nathan’s method is to create chaos on set and then task cast and crew with conducting it all together. Joy’s ferocious insistence that being an artist is the central component of her life is reflected in the equal priority Carol & Joy accords to the fullness of its artistic collaborators. Between the Temples’ hair and makeup artist Emily Schubert (who also sang “Wish I Was a Single Girl Again” on the soundtrack) is one of the regular voice students we observe mid-lesson in the Kanes’ living room. Joy directs her question about Maurice Ravel’s composition “Pour une infante défunte” to cinematographer Sean Price Williams. We also watch second cinematographer Hunter Zimny gently instruct Carol how to use his camera to film her mother (reminiscent of one of the the most moving scenes in Cutting My Mother, shot six years earlier, where Cindy asks Zimny, out of earshot of her son, for reassurance in her first outing as a director). The life Joy has arrived at, through nearly a century of resilience contending with the brutalizing expectations imposed upon women, is reinforced and echoed in every aspect of the film’s form; least of all, in the tremendous work Carol Kane has done over her long and remarkable career.

Using 16mm film to record an unstructured sit-down interview is a race against time, and Carol & Joy builds unexpected tension through the inevitable, often darkly funny ill-timed roll-out of the film. The first, as Joy is describing childhood abuse—“I don’t know what happened to me. I know that my father…”—is interrupted by a shouted chorus of “roll out!” and a cut to black. I found myself holding my breath as I intuited the approach of a 10-minute mark, pleading with the universe for a completed story, a desire that I recognized, with heartbreaking familiarity, as innate to the experience of life and all of the inevitable loss that accompanies it. The rhythm of the roll-outs gives the film the necessary sense that everything might be about to end before we’re ready for it. Trying to catch what we can, while we can, is a rare gift.

Carol & Joy is streaming on the Criterion Channel