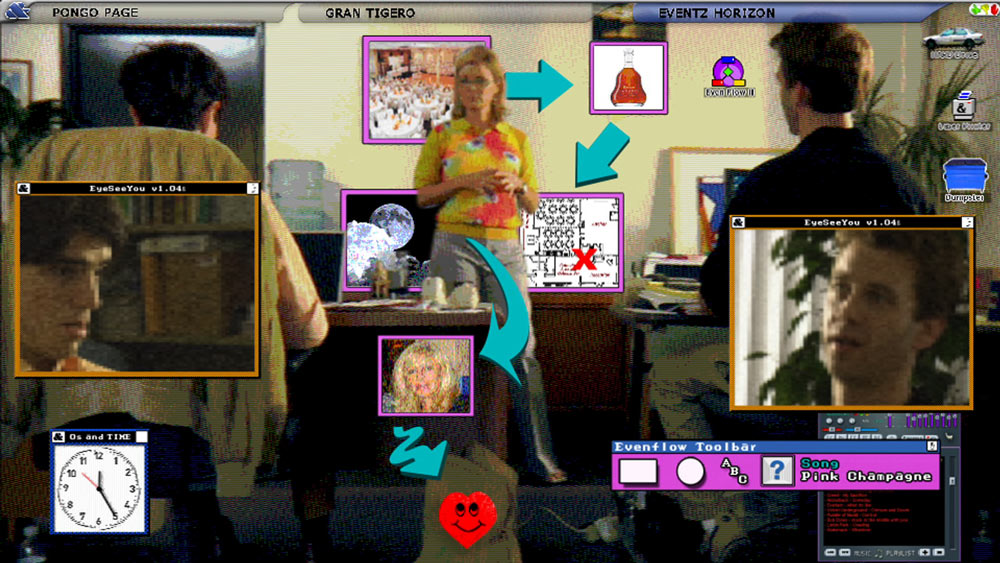

Filmmaker Eugene Kotlyarenko’s work has taken up the challenge of incorporating into cinematic storytelling the textures and rhythms of lives lived online. From his debut feature, 0s and 1s (2011), a desktop kaleidoscope of aimless hipsterdom, to Spree (2020), a satirical slasher formatted as an unbroken livestream, Kotlyarenko has combined psychologically rich character studies with the absurd deluge of text and graphics we forcefeed ourselves as pleasure and punishment. The films are refreshingly earnest, taking seriously the pain that animates the production and consumption of content without shifting attention from the comedic absurdity of the attention economy. Largely unheralded, he’s been doing his part to knock cinema off its current trajectory toward an ugly afterlife as a ghettoized legacy medium.

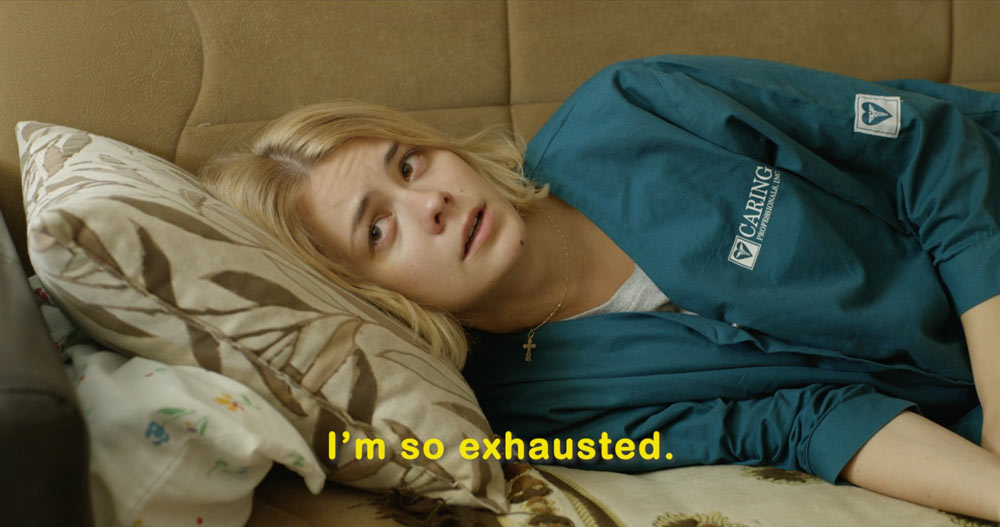

Wednesday evening, Kotlyarenko appears in person for the IRL premiere of his most recent jaunt through the digital frontier, We Are (2020, pictured above), a dreamy, metaphysical takedown of tech startup culture. The screening kicks off a spring series presented by the Rockaway Film Festival.

Kotlyarenko spoke with Screen Slate recently about cinephilia, Nicolas Cage, serial killers, directing himself, and TikTok.

Patrick Dahl: When I saw 0s and 1s a few months ago it felt like something I had been waiting for but hadn’t seen yet, which is funny because it’s almost ten years old at this point.

Eugene Kotlyarenko: We shot it in 2008, so it’s even older than that. And the idea goes back to 2004, and we had a short called 0s and 1s in 2005.

PD: I’m always looking at how new films incorporate screens, because it’s how most of us spend most of our time. And if you take a sample of film from most countries set in the present day you’d think that phones and screens play a much less important role in our lives than they actually do. There’s almost this anxiety about how best to incorporate this stuff and often the solution is just to downplay it or ignore it because that’s not why people go to the movies.

EK: Totally. I’ve been thinking about this for a decade now. I definitely was very combative in early interviews [about my work] saying “Look, the good directors for the past few years have only been making period pieces. Look at Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson. They’re making movies set in the 1860s or the 1970s.” They’re very good directors but they don’t know how to make this feel cinematic. In fact, the only director I’ve seen kinda tackle this in a way I think is interesting is Brian De Palma. When you look at Passion, it’s very aware of emails and Skype and surveillance. He’s always been aware of technology and has found ways to incorporate technology into his work and I admire that about him. Obviously, I’m happy people are finding Spree and Wobble Palace, which have drawn more people to my work and they’re then finding 0s and 1s and Skydiver [a desktop webseries from 2010]. With those two I was really aiming to be the next Godard, like “I want to change cinematic language. I want to bring to the forefront this way that screens colonize our consciousness now.” They’ve transformed us from passive viewers kind of looking through a window into another world through our screens, into active, immersive viewers who now have agency through the screens. And that has a whole new set of effects on a “viewer” or “observer,” because now you are the observed as well, and screens are not things that wash over you with their content, but something that becomes a part of you and your consciousness in a different sort of way.

PD: It’s funny you mention Godard, because I kept thinking of a Jonathan Rosenbaum quote, something along the lines of “most people who are compared to Godard are really just imitating stuff Godard was doing in the 1960s.” [the actual quote, from JR’s 1994 joint review of Ed Wood and Pulp Fiction: “...‘the new Godard’ mainly means the old Godard three decades later.”] We have a nostalgic sense of what the next blank is going to be, when really the next Godard will be pushing things in ways that will be easy to reject and difficult to sit through.

EK: People definitely rejected 0s and 1s, that’s for sure. It didn’t get into any film festivals. After a few years it had a weeklong run in New York, but it didn’t make any of the waves that I wanted it to. There was no critical attention. 0s and 1s almost has some sort of metaphysical or metaphorical approach to screens, where the justification for the desktop-izing of the narrative is just philosophical. We’re all kind of disconnected by these technologies so I’m going to visualize the different ways in which these technologies disconnect us and influence our view of one another.

PD: I imagine you head down a lot of rabbit holes when you’re researching and writing.

EK: I’m a filmmaker and an artist and I’m just observing the world around me and there are certain things I’m naturally drawn to. And internet culture has clearly consumed and taken over our reality and consciousness and self-worth. So I’d be remiss to not be interested in it. I’m very familiar with certain streamers, certain celebrity streamers as well as mass murderers. That’s fascinating because they’re the dark side of our attention-seeking consciousness. Mass murder since Columbine, and probably before, has a lot to do with attention. And our existence on social media has a lot to do with attention. So Spree is where the venn diagram of those two things intersects.

PD: Something I think about almost weekly is the video diary of Ricardo López, who was a stalker of Bjork and eventually killed himself in front of his video camera. It’s a straight-to-the-vein confrontation with an actual, violent attention-seeker who’s mentally ill, and there’s also the ethics of consumption to consider every moment.

EK: I’ve seen Elliot Rogers or the Parkland shooter or Virginia Tech, or this guy Randy Stare, who worked at a supermarket and killed one person there but tried to kill others. You can see in all of their videos a very transparent delusional performativity at work. But they’re not very good actors so you can see through to the sadness and vulnerability and all the desperation that they’re trying to hide as they play villain and mastermind. I thought there was something there in that type of performance. Much as reality TV has aged and gone through iterations, social media has gone through its own iterations. What we used to call “authenticity” in social media is now a super-studied pose. There are signifiers that suggest authenticity which at this point also feel artificial but in the early 2010s people could study and replicate them and convince many viewers that they were being real, when in fact it was a performance. So when I was watching these horrifying videos of these murderers, I saw a performativity that wasn’t that different from that of a wannabe influencer. And I thought it was important to expose that and make fun of this behavior.

PD: I don’t know if you’re interested in TikTok at all…

EK: Yeah, I am, of course.

PD: The opportunity for people, especially marginalized people, to directly share their experience, is really incredible, but the way each clip is packaged as a bit, even the more serious ones, makes it an ambivalent experience for me because you always have to question what you’re seeing and consider how people turn their experience into content and what kind of look you’re getting into people’s lives.

EK: The medium is the message, right? Every media has its own limitations and linguistics. And whenever the linguistics become codified, you just find people exploiting the form. And the things that feel really fresh are the things that subvert the form whether consciously or not. The things that stand out exploit the form beautifully or are so bold that they demand attention outside of the parameters of the formula. I think that’s true of every medium. And TikTok is distinct from Instagram and all apps have their parameters and their own language. Not many people can figure out how to do more than one of them correctly. Peter Watkins talked about something called the monoform. We get used to a very limited use of language and it’s used to tell very limited types of narratives and explanations and it’s very hard for anything that subverts it to break through using that language.

PD: Now you have a century-old medium and you’re finding ways to incorporate ways we’ve shifted away from the medium back into the medium. Did you ever consider along the way making video art or web art instead of feature films?

EK: When I was making 0s and 1s I was curious: “Was anybody using the internet and using computer aesthetics to make something?” And I found a lot of people who are basically my age doing digital art, artists like Jon Rafman and Petra Cortright and Daniel Keller, and I became friends with them. These were people who were interested in internet culture and wanted to make stuff concerned with it. And I was like “I’m the filmmaker one.” Along the way, in the last 15 years I’ve had installation pieces shown at galleries as well as diary films, pre-Instagram stories. That’s all interesting to me. I’ve also done social media experiments that are secrets, that are basically stunts that no one knows are fake. I won’t get it into what those are, but those things kind of went viral.

PD: Are you retired from acting?

EK: I don’t know. I acted in my own films out of necessity, because I would be the easiest resource. No one’s life would be easier to access than mine. If we’re shooting something in seven days and a location falls through, we always have my house. I’m not retired; I’ll do it again if I have to, but I’m hoping to upgrade to the next level in terms of production logistics. But if there’s something that’s so personal that I can’t raise money for it and I can’t trust other actors to be as shitty and vulnerable as I need the character to be … that’s another thing about casting myself: I can ask myself to behave in ways that are cringey and easy to make fun of. That might be harder for someone who has their own image to maintain. That’s another rationale for it.

PD: It’s very disarming watching a narrative film where the filmmaker is as exposed as you are. I remember as a teenager seeing Fassbinder in Fox and His Friends with his dick out and thinking “whoa, that’s him, the director of the film.” You make a lot of sport out of your body in Wobble Palace and I think it’s really effective.

EK: The fact that he played the shittiest characters in his movies is one thing I admire about Cassavetes. There’s also the comedic tradition of Woody Allen and Jerry Lewis. And Spike Lee, too. There’s a lot of themselves in their films, making fun of their image. I also really like Adaptation for that reason. Thinking about technology and communication and the way that screens are constantly evolving and colonizing our minds, I’m fascinated with how to make a narrative out of that process. I feel like I’ll always want to return to those personal projects.

I also think you have to tease something out about your behavior in the real world. Probably my favorite Cassavetes performance is in Minnie and Moskowitz. He’s almost a tertiary character in the film, this married guy who’s loving and abusive toward the Gena Rowlands character, and I’m sure at some level he must have felt guilty about his behavior toward his wife. He made that shitty character in this loving movie and then became that shitty character. Very real. I think the diaristic quality in cinema is really important, in the face of all this fake authenticity and “reality” television. I’ve watched a lot of Makhmalbaf recently and Iranian filmmakers like Kiarostami and Panahi and Makhmalbaf invented a new form of cinema. Metatextual commentary on power and performance and cinema in ways that are very sophisticated and very funny. I definitely feel like I aspire to do something like that. There’s a lot of things I want to do: an adaptation of Jun'ichirō Tanizaki’s The Key, an epistolary book about a relationship that I’d like to update and tell the story through text messages, etc. I also want to win Nicolas Cage another Oscar. I think he deserves an Oscar for every performance.

PD: Cultural sensitivities aside, when he said what he was doing was “kabuki” it instantly clicked for me and I started to really appreciate how he violates the construct of naturalistic performances.

EK: Movie stars are basically auteurs, and Nic Cage is the most postmodern star of all time. He’s completely aware of what his appeal is as a star and he’s recalibrating that appeal constantly. He has a postmodern approach and kabuki is just one element. You could say you like the “natural” Nic Cage of Leaving Las Vegas, and it’s very hard to reconcile that with the mastery of a movie like Adaptation or Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call: New Orleans. Those are all different types of performance and they’re all amazing. He’s someone I want to work with as soon as possible. I want to access things that he hasn’t accessed yet. Maybe I can find some sort of vulnerability he has been hiding under all the layers of performativity.

PD: I think that’s one of the pleasures of movie stars, that discovery when they do something new. But what’s crazy about him is he’s already done so much and there’s still the sense that there’s so much more. You can’t say that about most movie stars. There is the sense that they have so much more, but mostly because they haven’t shown very much.

EK: Exactly. How many have stretched as far as he has? I would kill to see like five more variations on Tom Cruise.

PD: I’m obsessed with Tom Cruise. He’s left so many breadcrumbs throughout the years: The Color of Money —

EK: He’s great, but he’s also a great producer and the responsible producer in him limits his ability to be a balls-to-the-wall performer.

PD: I’ve always looked forward to him aging, greying and putting on weight until he’s like a William Holden-type. But he won’t allow it. The hair dye has gotten ridiculous.

EK: Slowly he’s becoming an aged Danzig, with the muscles and the hair. Maybe when he conquers space, he’ll be open —

PD: He’ll look down at the pale blue dot below and things will become clearer. He’ll return a new man.

EK: Yeah, he’ll come back as a second-act Brando, the pinnacle of acting.

PD: Another film I kept thinking about when I was reviewing your work was Speed Racer. Most films now are cut like they’re still joining strips of celluloid together, but to me it’s a no-brainer that we update editing schemas. There’s something to be said for grammatical continuity and legacy styles, but all that potential is just sitting there.

EK: During 0s and 1st I saw a Béla Tarr retrospective and in general I don’t think a slow-cinema style accomplishes the psychological impact that film is supposed to accomplish. But then the grammar of 0s and 1s was based on how I could make a maximalist film that was also influenced by slow cinema. I’m a maximalist: I like De Palma, I like Tony Scott, Fassbinder, Ophuls. I like Speed Racer. Here’s a frame, let’s put a bunch of shit in there. In Spree, we didn’t have wide shots, we didn’t have inserts, we didn’t have closeups. All the grammar that people were used to, that were in a conventional horror film or a conventional any sort of film, went out the window. We basically have medium shots the whole way through. You’re moving because the car is moving but the frame is static. I was trying to come up with a grammar that was exciting and spatially logical but rhythmically feels like a movie.

PD: There’s so much information in your films and always a new place to look. And upon reflection I thought of Tarr, who’s probably my favorite filmmaker, whose space takes on such a fullness when you have all this time to absorb it. Both approaches drown your eyes in information and ensnare you in a way that more efficient films don’t.

EK: When Bazin wrote about Renoir, he talked about the integrity of long takes, which allow the viewer to choose where to look. My favorite directors do that. Edward Yang and Robert Altman. But they both guide you. Altman has the illusion of these big open worlds, but he’s always guiding you.

PD: There is the sense in your work that the viewer won’t get all of this. As a viewer, you can’t read everything or absorb every detail.

EK: Overwhelming.

PD: Yeah, and there’s a paradoxical relaxation that sets in when I realize that it’s impossible to catch all of it, so I settle in and feel free to let my eyes roam across the frame.

EK: I think a lot of people feel the opposite. They find it overwhelming and they’re stressed out over what they’re missing. Definitely the idea of overwhelming was crucial to what I’ve been doing. I wanted to overwhelm people. We are all overwhelmed by the potentiality of all the information that’s coming at us. I want to look at the endless potential of cinema instead of rescratching the same surface. The visionaries of narrative did a lot of the work in the 1910s and 1920s and the results were codified and we’re kind of stuck in that. Why not try to work with it and update it and try new things?