Albert Pyun, hot off of three consecutive films for The Cannon Group, was hired to direct the sequel to their Masters of the Universe (1987) adaptation, which would bring back Dolph Lundgren as He-Man and be released in 1989. Not content with the idea that millions of dollars would be spent on just one film, Cannon’s fearless leaders, Yoram Globus and Menahem Golan, also engaged Pyun to simultaneously direct a live-action adaptation of Marvel’s Spider-Man. Then they ran out of money and both films were canceled. In true Cannon spirit, nothing could be wasted and Pyun was given the task of reworking the existing sets and costumes into a new script. Thus, Cyborg (1989) was born.

In a plot that feels, in our current climate, closer to reality than it likely did two-and-a-half decades ago, Pyun’s film concerns a plague coined “The Living Death” that has nearly eradicated human life on the planet. The remaining members of the CDC, in Atlanta, are working on a cure but need data that is housed in a facility in New York City. To retrieve the data, they enlist a willing participant and augment him into a cyborg so that he can survive the quest. Naturally, things don’t go according to plan and she ends up being rescued by a mercenary, played by marquee attraction (and Dolph Lundgren replacement) Jean-Claude Van Damme. They spend the rest of the film journeying back to Atlanta and fighting for their lives.

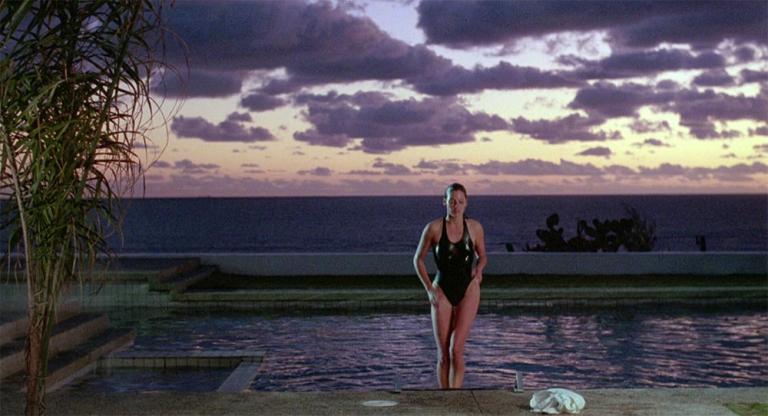

Pyun was no stranger to the post-apocalyptic aesthetic, having directed the post-atomic detective comedy Radioactive Dreams (1984) and two center of the earth films: Alien from L.A. (1987) and Journey to the Center of the Earth (1988). In Cyborg, he fully leans into the barren wasteland and decrepit steel urbanity of a decimated United States, pushing his meager budget as far as possible. As per usual with Pyun, his imagination and ambition outsize any dollar amount he could have ever accessed, but the film never feels handicapped by it. The borderline couture costumes hint at what was to come in 1992’s sunglasses and leather coat adorned Nemesis, offering a vision of the future that meshes environmental tragedy with elegant fashion.

Cyborg has now become legendary for being the final Cannon Group film to get a theatrical release, relegating Goram and Globus’s contributions to cinema to the burgeoning direct-to-video market of the ‘90s. It was also notoriously compromised by Cannon, Van Damme, and the MPAA on its journey to the big screen. Pyun’s original vision for Cyborg was devoid of much dialogue and more akin to a violent drama than the fight-fueled action films Cannon and JCVD were looking to make in the late ‘80s. But the marquee star ultimately got his way and Pyun’s more operatic film was recut to be more action forward. When Van Damme’s recut version was submitted for rating, it was repeatedly given an “X” by the MPAA, causing multiple instances of gory violence to be excised so that it could get the R-rating it needed for wide theatrical play. Decades later, Pyun discovered a VHS of his original cut and released it on European home video. This resulted in a film re-titled Slinger, which is notably different from Cyborg in just about every aspect. Slinger is Pyun’s film, through and through. It’s pervasively grim, more quiet and artful, and has less of an interest in the choreography of violence as it does in its gruesome aftermath. Cyborg, on the other hand, is a classic JCVD vehicle. It is kinetic, by comparison, and edited with one mission in mind: to make its star look incredible. And, it does.

Cyborg screens tonight, September 25, at Nitehawk Prospect Park on 35mm as part of the series “Ridiculous Sublime.”