A Body To Live In (2025) is a film in tension with itself. Angelo Madsen’s refracted portrait of the performance artist Fakir Musafar is as opaque as the man himself, compiling graphic glimpses of his lifelong practice in body modification with photographs, writing, and audio interviews. The film provides an overview of the man’s life, yet keeps the viewer at a distance from the controversial figurehead of the modern primitive movement. Where Madsen finds himself most at ease is collaging his archival material into a broader meditation on communities that privilege the human body as a vessel for spiritual transcendence and sexual transgression.

Madsen’s narrative structure largely adheres to a conventional chronology, charting the spiritual and artistic development of Musafar, whose given name was Roland Loomis. His Lutheran upbringing in Aberdeen, South Dakota, intensified his interest in exoticized depictions of indigenous cultures gleaned from National Geographic issues, as well as inspired him to conduct clandestine experiments in body piercing and bondage as a teenager. Following a stint in the U.S. Military stationed in Korea, Musafar emigrated to California. It was there that he found his tribe, so to speak, and became a figurehead in San Francisco's kink community. In the 1980s, he became one of the founders of the modern primitive movement, which practiced traditional rituals like scarification and flesh hook suspension.

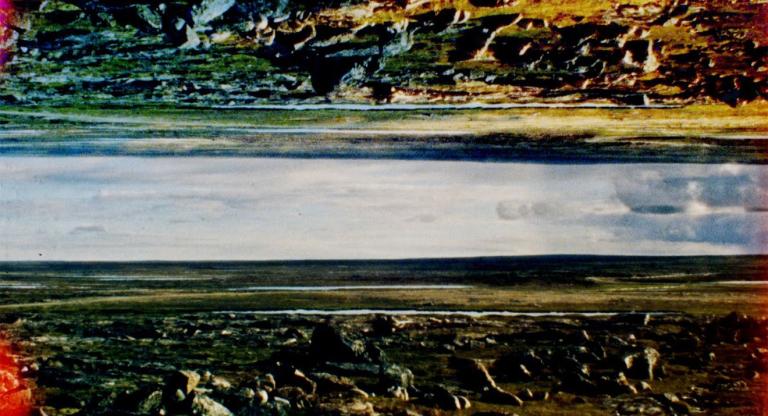

Accounts of Musafar’s professional accomplishments and personal relationships are punctuated by formal flourishes in Madsen’s film, including haptic emulsions and archival interpolations. This mise-en-abyme evinces the punk alterity that dominates Musafar’s mythos, even as it sometimes threatens overfamiliarity with the avant-garde stylings of queer pioneers like Kenneth Anger. Musafar’s carefully curated public image also doesn’t, by Madsen’s admission, leave much room for contending with his contradictions. While the film acknowledges the degree of cultural appropriation that enervated Musafar’s utopian pursuit of spiritual, sexual, and artistic self-expression, it curiously elides any modern offshoots that serve as a corrective for these flaws.

Both a virtue and a limitation, the film privileges those closest to Fakir, particularly his professional and life partner Cléo Dubois. Furthermore, Madsen strives to exhume the ghosts of those who found spiritual and erotic communion in the queer Radical Faerie community, many of whom died from AIDS-related complications. By relegating the interviewees, including Annie Sprinkles and Ron Athey, to audio-only excerpts, the film’s depersonalization of its most famous figures gestures toward an egalitarianism that gives it an empathetic fecundity. When not overwhelmed by the legacy of its protagonist, A Body To Live In’s veneration of its subcultures movingly foregrounds kink as an impetus for communally nurturing shared humanity through vulnerability.

A Body To Live In screens this evening, May 4, at Metrograph as part of Prismatic Ground 2025.