Andrew Castillo, translator, writer, teacher, and now programmer of “Cinema Blues” at the Maysles Documentary Center, also once had a show on WKCR, Jazz Alternatives, that, among other impressively exhaustive programs, dedicated a handful of episodes to jazz soundtracks and film scores. This multifaceted experience is manifest in Castillo’s “Cinema Blues” series, a program of jazz documentaries that began in February of this year, and will continue on through early summer.

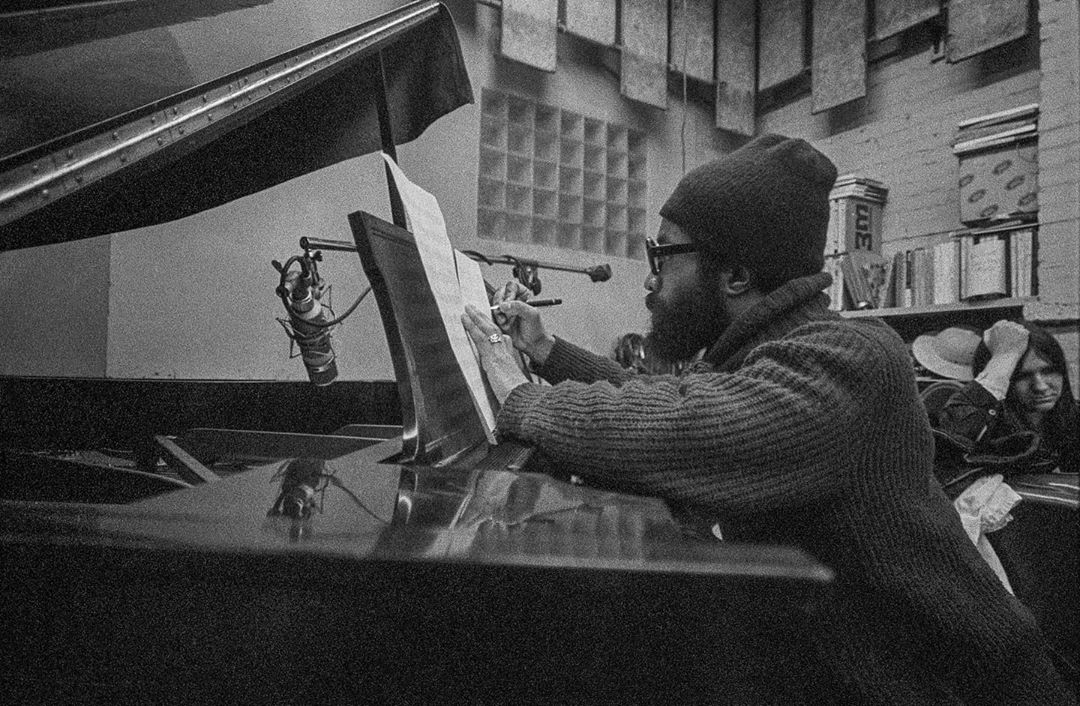

The series’s conceit positions itself within a hazy set of parameters: many of these films run at lengths that fall between “short” and “feature”; some feature performances by musicians, others might eschew said musicians’ choice of instrument completely. Such concerns, however, are liberating for Castillo. The projected length of the series finds him mixing and matching films on their thematic and aesthetic merits, rather than stressing the over representation of certain musicians and vaunted scenes. Thus far, we’ve seen Jackie McLean enter academia in the 1970s (Jackie McLean On Mars, 1980), Tony Williams communing with African drummers in Dakar (Tony Williams in Africa, 1973), and Blues Like Shower of Rain (1970), which as the title implies, centers blues music rather than jazz, and acted as an enriching supplement to series, broadening the musical history on display.

In keeping with the protean nature of the films themselves, many programs have also ended on solo instrumental performances, or far-reaching panel discussions. Imagine the Sound (1981) was followed by a Q&A with three musicians: Stephen Haynes, Santi Debriano, and Marc Edwards. (Edwards has now become a familiar face at these screenings, whipping out his iPhone to chronicle as much as he can, from quick profile shots of people such as the saxophone giant Ben Webster on-screen, to recordings of the intros and performances; his passion is infectious.)

Castillo and I spoke before John Jeremy’s Blues Like Shower of Rain and Jazz Is Our Religion (1972). Both films are spirited assemblages of still photographs and sound; the latter’s images were provided by Val Wilmer, photographer, and author of the free-jazz bible, As Serious As Your Life.

Patrick Preziosi: What has been your process in sequencing the programs, and then the films therein? You began in a relatively contemporary milieu with Rising Tones Cross [1985], and then jumped around. Even the trade-off between black-and-white and color these last few months has felt to be of a larger design.

Andrew Castillo: A lot of it is intentional. The first thing I thought of when approved for this series was getting the major films as far as features go, which was Rising Tones Cross, then Imagine the Sound, and tonight’s screening, Jazz Is Our Religion. At the time I didn’t realize it, but I didn’t want films that really focused on individual personalities, or big stars, not only because it’s been done, but because the emerging theme of this series has been that of the ensemble.

With the features decided, I thought I’d alternate those standalone films with the shorts programs. But none of the shorts programs themselves so far have looked how I thought they would, because of the availability of the films. Things fell through early on, things fell apart at the eleventh hour. It’s something I’ve learned about programming, that even when you know who has the film, and you’re ready to pay them and honor them in any way, it still doesn’t mean it’s going to happen.

The second program, “Survival Blues,” which was the Charles Mingus film and the Jackie McLean film, was supposed to have four films in total, the other two focusing on David S. Ware and Weldon Irvine. When the latter two didn’t work out is when I had the idea to add music as a counterbalance, speaking to those two films in ways that additional films wouldn’t. For a program like “Contemplation,” I was very conscious of going back and forth between color and black-and-white, and going back and forth between time periods in a way that wasn’t lopsided. There was also supposed to be a fourth film then and when that fell through, I brought in the trumpet player, which, to my mind, is as good as a color film. The trumpeter was like a contemporary color film. He had the same kind of dynamism. It’s like a playlist, it’s something I always consider. Fit the music in wherever you can.

PP: In rewatching these films, have you picked up on any unifying threads you hadn’t before?

AC: As much as I love these films––and as much as I love films in general, not just jazz documentaries––I’ve only ever seen them once. You’re almost afraid to watch them again, or you’re too busy trying to watch new things. Most of the connective tissue comes together in my head as I watch the films, and that goes hand-in-hand with rereading things. For instance, I’m rereading Francis Paudras’s Dance of the Infidels: A Portrait of Bud Powell, which I’d read years ago, and I hadn’t realized Bud Powell is mentioned in the Jackie McLean film. I knew Bud would come later in the series with StopforBud [1963], but now he’s even more of a connection.

PP: So far, these films generally have a strong pedagogical undergirding to them. Was that intentional, or is it more coincidental? Education seems such a constant––though underrepresented––element in jazz that the more casual listener might not key into had they not seen these films.

AC: That’s a theme that’s emerged. The more films I watch and the more programs we pull off, the more I understand how important and natural an extension education is of the jazz tradition. A lot of the musicians turned to education and academia in the 1970s because they didn’t have gigs, like McLean at University of Hartford in Jackie McLean on Mars. I did intend for the programs to be more issue-oriented than predicated on musical stars. I didn’t want to simply have a “Miles Davis Night” or a “Thelonious Monk Night.”

PP: During the panel discussion following Imagine the Sound there was a lot of talk of the intersection of the jazz teacher and the jazz musician, surrounding Bill Dixon especially.

AC: Along with Cecil Taylor, Dixon was one of the first to make that pivot in the mid ‘70s. The seventh program will actually be dedicated to just one person, but it will be a mixed media event about Bill Dixon and the October Revolution in jazz. There’ll be a gradual progression from where we are now––Bill Dixon grew up up the street––to the larger scene in New York, to education. Education is an essential facet of self-determination: it’s making your own infrastructure to teach, and to subsequently pass down your legacy and the culture of jazz down. I want people to be as inspired as I am.

PP: In Jackie McLean on Mars, you see McLean disrupting the formal rigor of the academic setting. There’s a scene where he’s reasonably combative with his students. I love when he says they always expect him to start with someone like John Coltrane, but he actually begins with the JFK assasination, acknowledging the larger world in which he creates and teaches. You have to be aware of everything that’s happened.

AC: McLean has a natural way of flattening these issues, of taking the perspective of someone born-and-raised in New York City, of someone who’s a musician, someone who’s had a fair amount of trouble with the law, of an artist who traveled the world, and to me, that’s politics— collapsing those distinctions.

In modern music, you see a lot of people capitalizing on the history and legacy of jazz, but you don’t always see the origins, the entertainment has been divorced from its tradition. The reason we go back so far with films over sixty years old is that the connection is still intact.

PP: I’m used to stumbling upon a lot of these documentaries on YouTube and whatnot, so what’s been the reaction from rights holders and filmmakers about screening these films?

AC: As far as the filmmakers go, they’re thrilled, as well as a little surprised. I’m used to the same jazz documentaries being trotted out when the music is temporarily in vogue, but you don’t get a series showing deep cuts, much less deep cuts back-to-back.

John Jeremy, who lives in England, told me he’s very happy this event is happening in Harlem because so many of the images used in Jazz Is Our Religion come from Harlem. I’d love to do an evening of recorded performances, beyond proper films, but unfortunately, that’s where the rights get tricky.

PP: How did you find some of these more obscure shorts in the first place?

AC: They came from listening to music, looking up musicians on YouTube, downloading .zip files from community sharing sites of rare albums ripped straight from vinyl. A lot of this is practical, too, seeing the musician you couldn’t see otherwise in a live setting. As someone who considers himself a cinephile, I did initially compartmentalize. I had the art films that I love on one side and the jazz films on the other, but with time I’ve realized there’s an overlap, which is also what this series is about.

PP: You mention seeing an artist you can’t see live. When it comes to jazz, when you discover an artist there is no guarantee that you will be able to find footage of them playing, or even hear their voice in any capacity. It’s the tragedy of jazz history, that there is so much missing.

AC: The best example of that is John Coltrane. There’s no footage of him speaking. You may hear him praying on record, or his voice in background studio chatter, and yet he’s one of the largest names in music.

That’s part of a larger problem, where the music is still not getting the respect it deserved in the ‘70s and before. If it’s not making money, or doesn’t pay service to a specific sector, it fades away with time.

PP: There’s also so many unfortunate instances of rare performances buried in some European television studio’s vault.

AC: One thing I’ve learned from programming here is that the listed television archives are more than enough to program an entire series, and enough for however many CD or vinyl box sets! They’re essentially rendered invisible because they’re behind that wall. I was shocked by all that I found in the French media archives. Sometimes rights issues relegate films in beautiful fidelity to excerpts shared on social media.

PP: Because of how ubiquitous some jazz names are, people may assume there was more historical preservation being enacted when there really wasn’t.

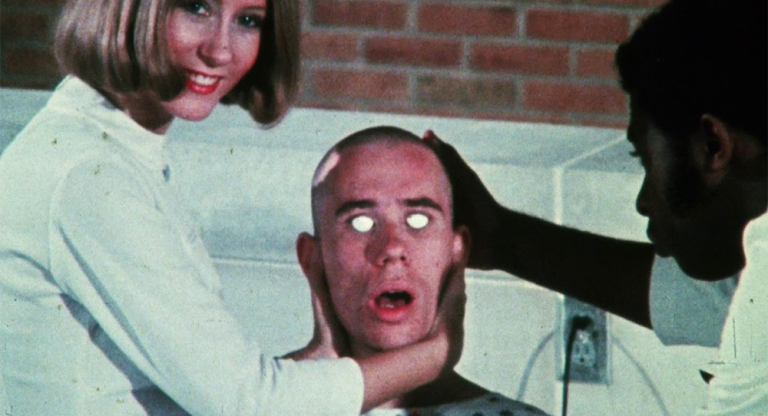

AC: It leads to desperation, in a sense. I remember when the Thelonious Monk film, Rewind and Play [2022], was released. It had a strange reception, where people saw him playing wonderfully, but they had to sit through this harrowing first third where he’s being humiliated by this TV host, and then not wanting to necessarily mention it, because this footage existing was almost too good to be true. Scarcity can lead to weird places, but exhibition is another tool to fight that. A conversation, a name on a marquee, an event to look forward to, that keeps it real in the age of streaming.

PP: Can you give a rundown of the program playing the night this interview runs, May 7?

AC: These shorts programs are named after compositions by pianist McCoy Tyner, because Tyner coined the phrase, “as serious as your life”, which became the title of Val Wilmer’s book, and I think the quote has been occasionally misattributed to Rashied Ali, as he’s on the cover of various editions. This one is called “Passion Dance,” my experimental slate, in the traditional sense: non-narrative films with an emphasis on sound, movement, color.

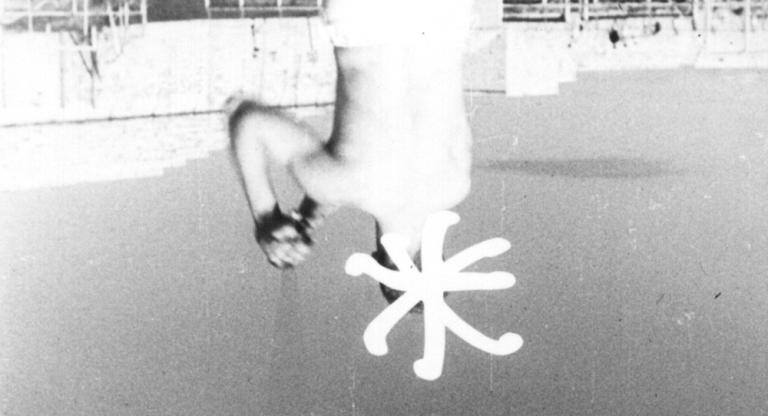

It’s a film that plays rarely, but we’re getting a 16mm print of Robert Fenz’s Vertical Air [1996] from the Harvard Film Archives. It’s the archetypal experimental jazz film, as it’s images and montage that react to the trumpeter Leo Wadada Smith’s music.

There’s a short that revolves around the poetry of Cecil Taylor. There’s a notorious Taylor album called Chinampas, where he doesn’t touch the piano, but instead uses percussion to accompany his poetry. Some of his poetry was featured in Imagine the Sound, and it’ll come back in this beautiful 10-minute short done on 8mm by Colectivo los ingrávidos, The Winged Stone [2023].

There will be a famous short on the music of Sun Ra, The Magic Sun [1966], which was the first thing I thought about for this program. There’s a moment in Mingus: Charlie Mingus [1968] where he’s playing bass, and the camera goes out of focus, shooting him from below, and the bass strings and his hands become so abstracted and beautiful. Something so beautiful that it rises to the level of accompaniment.

There’ll be a film having its premier: Eskis [2017]. Vincent Guilbert made a film in Japan about 10 years ago, where Jacques Coursil plays trumpet solo in the forest, and he’s so moved at one point that he dances. To me, it’s a perfect way to cap it.

The program will be followed by a performance by Brooklyn musician Rass Burnett, a third generation saxophonist. I asked him to bring his thumb piano and then switch to his tenor sax when he feels it appropriate. I’m going to encourage everyone to close their eyes, and to imagine their own film, to end the night.

After our conversation, I asked Andrew to throw together something of a “playlist” that he felt best encapsulated the program, taking into account the various musicians and songs. This is what he offered:

Bill Dixon - “Nightfall Pieces I”

Charles Mingus - “Freedom”

Langston Hughes - “Double G Train”

Bud Powell - “Blues for Bouffemont”

Charles Gayle - “Eternal Now”

Archie Shepp - “Scag”

Jackie McLean - “116th and Lenox”

Sun Ra - “Possession”

Ben Webster - “Blues for Mr. Broadway”

Cecil Taylor - “You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To”

“Made in Harlem: Cinema Blues” runs through June at Maysles Documentary Center.