If an angry gay anarchist reimagined Badlands for the 80s, what might we expect of its impressionable yet fiercely loyal protagonist? Would her family move to Orange County to start a Christian ministry? Could her relationship with her bad-to-the-bone boytoy be complicated by the release of his prison bunkmate? Might the musical refrain of Carl Orff's "Gassenhauer" be replaced by The Angry Samoans' "My Old Man's a Fatso"? And what if the whole thing was shot on video for $2,000?

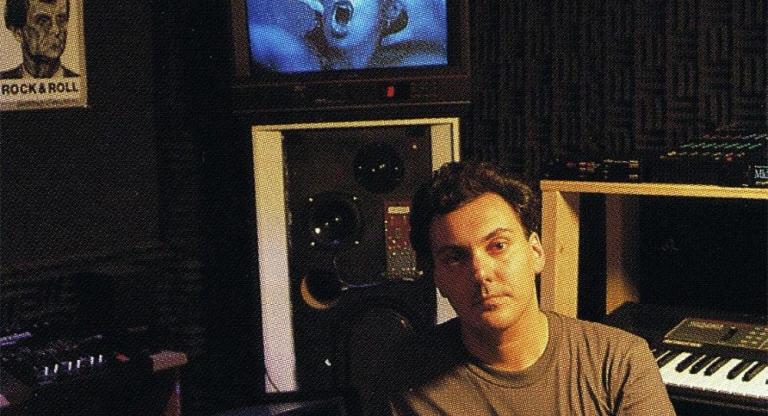

These questions are answered in Blonde Death (1984), which deserves a place alongside Bill Gunn's Personal Problems as a recently revived shot-on-video feature worthy of serious consideration within the cinematic canon. Its director, James Robert Baker – credited here as "James Dillinger" – is best known for his transgressive gay fiction like Boy Wonder (1985) and Tim and Pete (1993), the latter about rekindled former lovers on a death trip to assassinate the American New Right. Around the time of Blonde Death's production, Baker was an award-winning yet unproduced UCLA screenwriting grad, and this, his only feature, was realized under the auspices of Hollywood-based media arts center and video gallery EZTV.

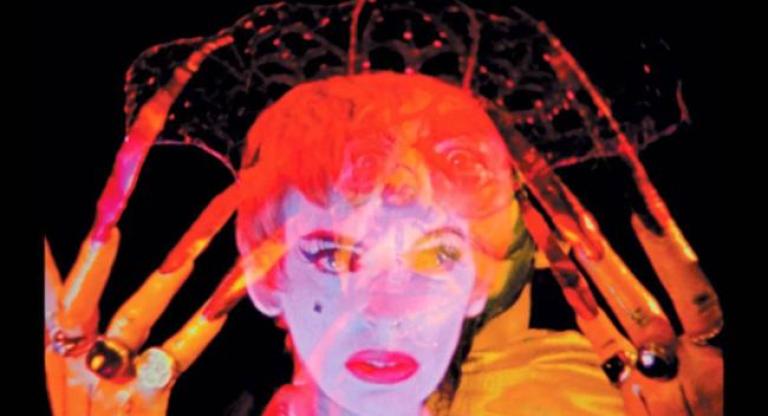

The result is a tightly structured, character-driven satire buoyed by pitch-perfect casting of unknown actors, including Sara Lee Wade as Tammy "the teenage timebomb," who narrates in an earnest voiceover with a singsong southern drawl. Tammy's parents espouse strict Christian values, but her potentially closeted father has a spanking fetish, and her stepmother, we learn, is scheming to murder him with poison Tang to inherit money to open a new church with her lover. When both are out of town, Tammy is aggressively courted by a one-eyed lesbian, but she instead falls into the thralls of a hunky home invader, with whom she plots to rob Disneyland to start a new life. (The eventual heist is shot guerrilla style within the Magic Kingdom.) But their plans receive a mixed blessing with the arrival of Tammy's new squeeze's prison lover, who is embraced as a third partner—but may be a homicidal maniac.

Blonde Death is rich with cultural clutter: doomsday churches, singing televangelists, pill-popping, Mickey Mouse, and knotty sexual confusion. But Baker is uniquely talented at tying satire back to his characters, weaving a consistently engaging tapestry of transgressive societal commentary. And alongside the affinities with John Waters's oeuvre, Mudhoney, and Baby Doll, Blonde Death feels equally of a piece with the Abject Art of fellow Angelenos Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, or Bruce & Norman Yonemoto's videographic deconstructions of Hollywood mythmaking and melodrama. The result resists easy placement within the continuum of independent 80s cinema or video art; and while it seems like a tragic and unfair twist of fate that Baker's feature filmmaking career never took flight, such an outsider position seems to befit this perverse, uncompromising, and deeply felt work.