Batman needs an enema! One only has to take a cursory look through police department Facebook pages to see Batmanphilia in full effect, with particular emphasis on the Christopher Nolan and Zack Snyder interpretations. The former’s trilogy, starting with Batman Begins (2005), “rehabilitated” the Dark Knight—restoring his credibility as a hypermasculine menace after the gelding of Joel Schumacher’s Batman and Robin (1997). The Batman of the 1990s (Batman Returns [1992], Batman Forever [1995], and the unjustly maligned Batman and Robin), is part of a legacy of queerness and camp.

Film critic Richard Dyer describes camp as an opportunity for taste and performance to be used as social markers, enabling those at the margins, often queer folks, opportunities to assimilate into larger communities. Camp and its intersections with queerness have long been affiliated with the Batman brand. So prominent were the themes of queerness and BDSM in the early Batman comics that psychiatrist Fredric Wertham “outed” Batman’s kinks in his infamous comic-shaming book, Seduction of the Innocent (1954) (for more see Sasha Torres). Batman has long occupied space in queer culture, from Adam West in spandex to Andy Warhol’s Batman Dracula (1964), starring underground queer filmmaker/performance artist Jack Smith. In the 1990s, Batman may have reached its camp apex.

The character’s libidinous quirks are evident in the nocturne Batman Returns. The unlikely sequel to Batman (1989) gave more creative control to director Tim Burton, whose insistence on a darker tone cost the franchise its Happy Meal toy promotional tie-in. Although broodsome in tone, Batman Returns does not sacrifice the theater of the night as evident with the set design. Characters like the perverted, black-tongued Penguin (Danny DeVito), cartoonish CEO Max Shreck (Christopher Walken), and the latex-clad, dominatrix-adjacent, Catwoman (Michelle Pfeiffer) seem to materialize Wertham’s psychoanalytic panic. Catwoman’s whip is at once a metaphor, a sex object, and a weapon. The film pries open Batman’s sex life into spaces beyond normative hetero-masculinity. As the late scholar Lauren Berlant argues, heterosexual sex limits the possibility of pleasure-driven sex because it often enacts and reiterates patriarchal values through specific sex acts. Batman Returns offers a rare cinematic glimpse of a superhero prioritizing pleasure over performativity.

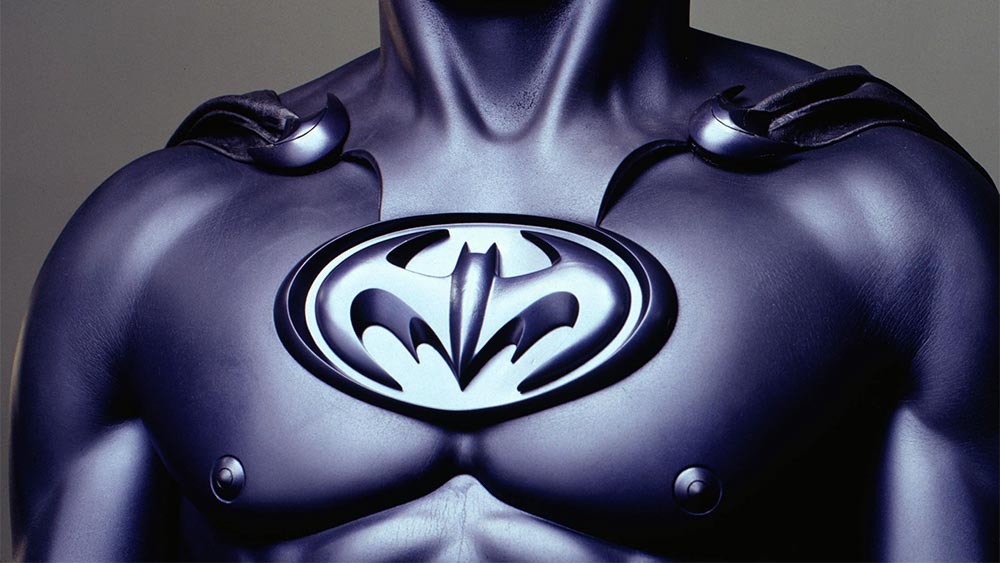

Batman Forever (1995), firmly steered the Dark Night into the realm of queer excess, both in terms of narrative coherence and visual aesthetics (as evident in the infamous implementation of nipples on the Batsuit). The chaotic tone of the film is partly due to the script having been doctored by multiple writers, including Akiva Goldsman. Joel Schumacher took over directorial duties from Tim Burton, who retains a production credit. Michael Keaton left the cowl for the dashing Val Kilmer to step into the eroticized suit. The production shake-up was part of an effort to appease the corporate overloads that sought merchandising opportunities from the film. That directive breeds creative excess that led to wardrobe changes, a redesign of the Batmobile, and a more dramatic Gotham, now teeming with Michelangelo-esque nude statues, over which the camera lingers.

The introduction of Bruce Wayne’s ward, Dick Greyson (aka Robin), only enhances the distinctly queer space of the film. Rather than cast a young teenager, as the character is typically portrayed, the studio went with Chris O’Donnell, then 25, passing over the original, ambitious casting of Marlon Wayans. While the move was no doubt a way to avoid any allegations of an intergenerational romance between Bruce and Dick, it intensifies those queer rumors by having two young single men living in close quarters with nipple costumes.

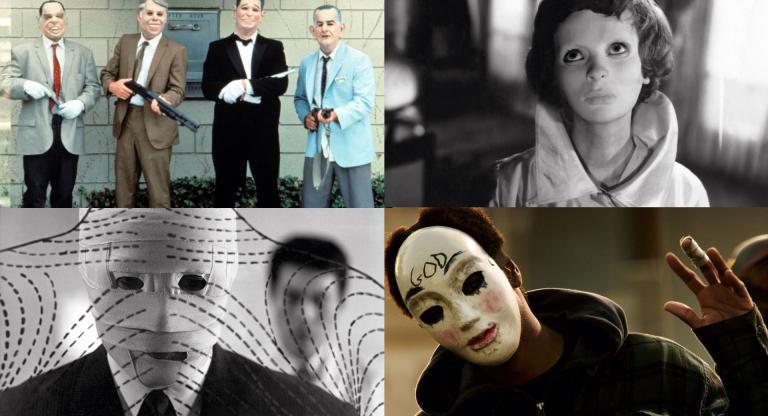

The scholars Kara Keeling and Steven Shaviro both describe rumormongering around same-gender characters as a queer labor built from a film’s aesthetic and narrative excess. Of course, they argue, films financially benefit from this queer labor for it is a critical labor for "bad" films to exploit and generate engagement, an argument more fully fleshed out in Matthew Tinkcom’s Working Like a Homosexual: Camp, Capital, Cinema. The resulting multimedia documents (fan art, videos, and fan fiction) generate, in a circuitous way, profits for the studios. Taking their cue from Gilles Deleuze, Keeling and Shaviro situate cinema as a mobile affective register. Since the mid–twentieth century, the “cinematic” has bled through the theater screen to include the ephemera associated with a film. Directing our gaze toward the cinematic objects affiliated with Batman in the 1990s, we collide with key queer icons as seen in the Herb Ritts’s promotional photography that further exploits Batman’s eroticization evoked in the films. Ritts’s lush platinum-like B&W prints re-orient the viewer’s relationship with the costumed body of Batman that emphasizes his nape and clavicle, while the villains deliver expressive face contortions in tight close ups.

The franchise reached a frenzy in Batman and Robin, a film that is best understood as a mainstream contribution to queer film history rather than a serious comic-book outing. George Clooney replaced Val Kilmer for a sequel in which the homoeroticism between Batman and Robin is so central to the plot that Poison Ivy act as a third wheel between them. Perhaps the only actor acutely aware of what kind of film they were in, Uma Thurman brings villainess camp excess that rivals even Pfeiffer’s Catwoman. Poison Ivy goes full drag, creating a glamourous object for audiences to latch onto, not unlike the characters played by Marlene Dietrich. And the Dietrich reference is not accidental, for the film’s standout scene—Ivy’s introduction—is a direct homage to Dietrich’s performance in Blonde Venus (1932), in which she emerges from a gorilla suit. The nearly shot-for-shot recreation of a classic piece of Hollywood camp is deflated by the introduction of the Batman credit card, used to bid on a date with the femme fatale for the Gotham City Charity Ball (hosted by Batman no less).

Batman and Robin is stuffed with visual gags and acts as a pop-culture grab-bag featuring cameos from Vivica A. Fox, Coolio, and Elle Macpherson, whose character is essentially a beard for Clooney’s Bruce Wayne. Ultimately, the queerest and campiest sequence in the Batman films of the 1990s is Batman and Robin’s ninety-second opening, in which the title characters suit up for battle, featuring tight shots of their nipples and a prominent butt jiggle as they pull up their pants.

The Batman of the 1990s is more in line with the character’s comic-book origins than the recent cinematic portrayals of a hypermasculine, militarized vigilante. In these three films, we are provided with the substance of brilliant camp: a costumed man prancing around rooftops at night.