“Masterpieces have many possible ports of entry” writes Jonathan Rosenbaum of Pere Portabella’s Vampir Cuadecuc (1970), in the liner notes for a 2019 re-release of the film’s soundtrack. He recalls the rapturous experience of seeing it at Cannes in 1971, despite being ignorant of the significance of Carlos Santes’ musique concrète score. For Rosenbaum, with his “rampant cinephilia,” the port was the film’s daring conceit: an avant-garde documentary of the making of Jesús Franco’s Count Dracula (1970) that, crucially, could “shift his narrative focus within single shots from the Dracula story itself to the filming of it.”

Widely accepted as a political allegory for the Franco regime and a layered work of metacinema, Vampir — which follows the same sequence of Jesús Franco’s film — is its own Bram Stoker adaptation. And within those ranks, it’s a truly original take on what may be the most well-worn source novel in film history.

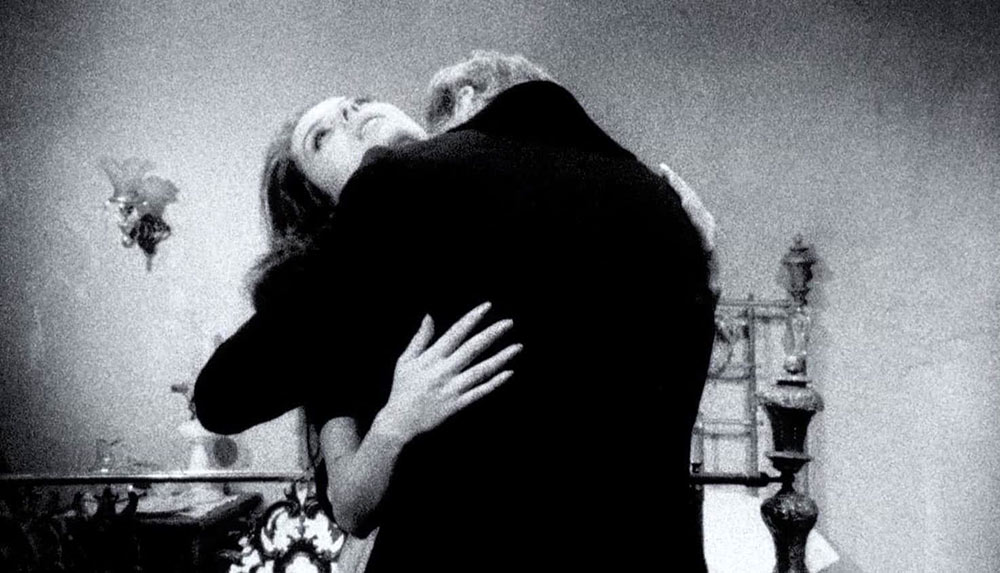

In Portabella’s film, Dracula (Christopher Lee, no less) breaks the fourth wall to blow raspberries or to take a playful swipe before climbing into a coffin to be covered by polyester cobwebs. Lucy Westenra smokes in bed; Mina Harker wears a leopard-print coat and seductively winks. All is set to alternating tunes of proto-industrial noise and lackadaisical lounge music.

Looked at alongside other titles in the Dracula canon, Vampir’s ingenuity remains intact but not without precedent; Portabella seemed interested in more than one filmmaker’s interpretation. Its erratic speed, grainy, black and white cinematography, and (near) silence recall early genre (and cinema)-fomenting work like Nosferatu and Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr. The scrappy circumstances of its making, on the other hand, parallel those of George Melford’s 1931 Spanish-language Dracula, shot simultaneously with Tod Browning’s version on the same sets at night.

Vampir also portended evolutionary shifts in the genre. Portabella’s focus on artifice, in particular, preceded a profusion of spoofs that — unlike Abbott and Costello fare — poked fun at cardboard castles rather than the goofballs thrown into them. Vampir isn’t without humor, often at the expense of Jesús Franco’s unimaginative set dressings. In one of the film’s funniest moments, Dracula in bat-form — ostensibly Lee, seen seconds before 6’4” and hissing — escapes Lucy Westenra’s room through an open window. Portabella takes a sidecar view from the plastic creature’s wing as it zooms on a clothesline out to safety. The shot wouldn’t be out of place in 1995’s Dracula, Dead and Loving It.

Professor of Spanish film Steven Marsh has likened Vampir to a “photo negative” of Jesús Franco’s film, “in that it interrogates, in its avant-garde engagement with genre film, apparent oppositions and questions of discordant representation.” It also often simply looks like a photo-negative, such as in a lengthy scene of Dracula and Jonathan Harker conversing by a fire. Portabella positions his cameras to face bright stage lights, flattening actors’ features and impressing an after-image of himself: an iconoclast breaking the 180-degree rule to stare at the sun.

Its entry ports are indeed arterial, but Vampir’s most navigable one demands nothing more than familiarity with a classic tale. Inside its oneiric atmosphere, there’s space for deep thinking and passive awe.

Vampir Cuadecuc is streaming on Mubi and Kanopy, available to digitally rent/buy through Projectr, and on region-free Blu-ray from Second Run.