To mark the centenary of Amos Vogel’s birth, a citywide tribute is being held for the influential film programmer and connoisseur of the avant-garde at multiple repertory venues. Screenings that have recently or are soon to take place at Light Industry, Metrograph, MoMA, Roxy Cinema, Anthology Film Archives, Film Forum, Film at Lincoln Center, and the Museum of the Moving Image focus on various aspects of Vogel’s career, among them his seminal book, Film as a Subversive Art (1974), newly revised and reprinted by Film Desk Books.

A guiding encyclopedia for film programmers and enthusiasts alike, Film as a Subversive Art illustratively catalogues more than 500 films Vogel came across as a programmer, principally through his and Marcia Vogel’s film club, Cinema 16 (1947-1963), and also as a co-founder of the New York FIlm Festival. The book also serves as a treatise on the revolutionary potential of cinema: its ability to change consciousness, reflect the human condition, and subvert the status quo. In Paul Cronin’s 2004 documentary, Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16, Vogel states his definition of the word subversive as “anything that changes or undermines previous ways of thinking and feeling. Subversive art makes you look at things in a new and very different way. It disrupts. It destroys, and thereby builds up new realities and new truths."

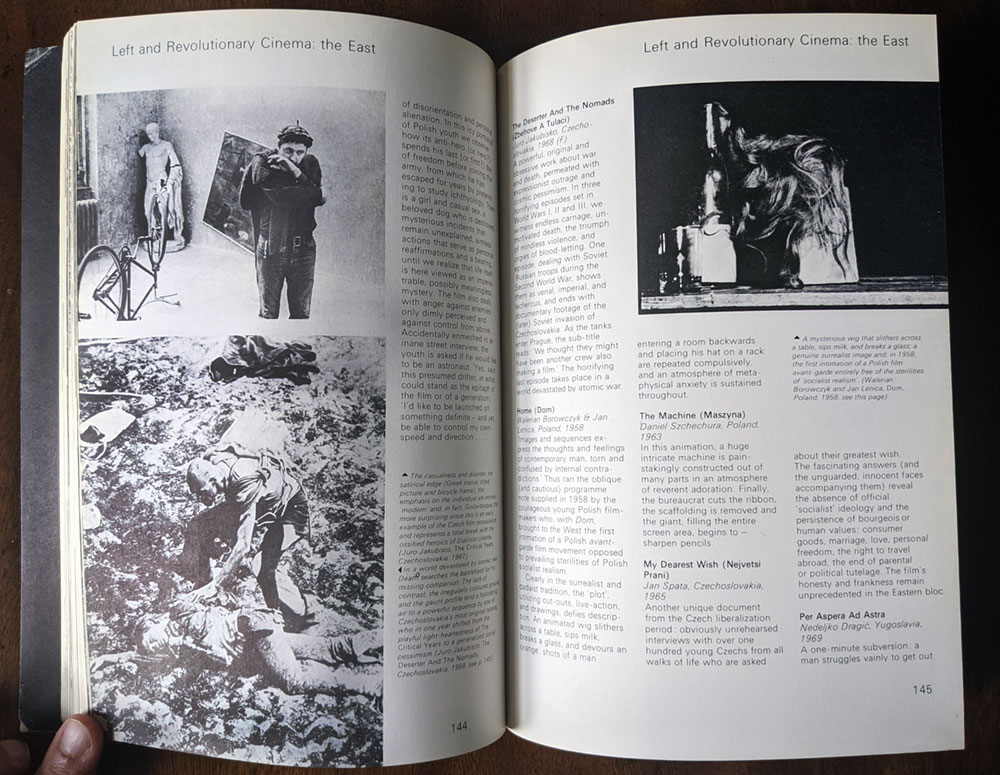

Each section begins with a different kind of “Weapon of Subversion”— Subversion of Form, Subversion of Content, and the Forbidden Subjects of the Cinema, and Towards a New Consciousness—broken into chapters such as “The Triumph and Death of the Moving Camera” and “The Power of the Visual Taboo.” Each contains short analyses of dozens of films, ranging from established quantities like Godard and Welles to anonymously made sponsored and medical films. Aside from the films themselves, Vogel is particularly concerned with the cinema-going experience as a mode of liberating the consciousness. In the theater, viewers sink into the “womb-like” darkness of the space, between waking and dream states, free to reject “rational faculties” and “customary constraints.”

The contemporary reader is compelled to consider the fragmented viewing experience of today’s cinema, mediated by algorithmic judgement and dictated by authoritarian doctrines. Vogel predicted this evolution of cinema. At the time of his writing, film was already a weapon of capital, used to insulate “the masses” from the subversive message. The plight of our film culture makes the resurfacing of Vogel’s book especially timely.

Out of print since 1987, Film as a Subversive Art was republished in 2005 in a facsimile edition that also quickly went out of print. As the centenary approached, Jim Colvill and Jake Perlin of Film Desk Books worked to make the book available again. They didn’t start out with grand ambitions to update the text, but the original negatives from the first printing were no longer usable. They ended up re-typesetting the entire book and re-scanning almost all of the hundreds of images from the Amos Vogel archives at Columbia University. Colvill and Perlin also didn’t anticipate the number of inaccuracies that would eventually lead them to undertake a major revision. They contacted film programmer Herb Shellenberger, who became a detective of sorts, assiduously tracking down correct details of the films referenced in the book. The inaccuracies weren’t necessarily the fault of Vogel: “He was seeing these films for potential festival inclusion because he juried for Oberhausen and Cannes, Berlin, and obviously New York Film Festival,” Shellenberger told me. “Any information that he was given that was incorrect would have been repeated in the book.”

For instance, English titles were listed for films never screened for English-language audiences. Shellenberger brought up the quest to verify an obscure student film about funeral services cited by Vogel, Poslední věci člověka by Jovan Kubicek (Czechoslovakia, 1967). The Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU), where the film is archived, had never heard of the title given in the book: Meditation on the End of Human Life. It was most likely never shown outside of Czechoslovakia. Other edits include discrepancies between premiere dates and production dates, diacritical marks, and shooting locations. Colvill and Shellenberger made careful editorial decisions to correct the record, but also to preserve Vogel’s essence. In the epigraph, Vogel misattributes a quote to Goethe: “Only the perverse fantasy can still save us.” Colvill decided to leave it as is.

For some, these types of inaccuracies may seem minor. But considering that the book has become an important tool for programmers over the years, it has also disseminated misinformation. “A big part of this is just making it more useful now,” Colvill said. “Its usefulness is continued into the present moment.”

The extensive collaboration to bring these films to New York audiences reinforces our need for collective film-viewing experiences, particularly in a period of uncertainty for cinematic spaces. “I've never seen this level of cooperation between all of the venues. It's pretty unprecedented.” Colvill said. “I think it speaks to the place that Amos holds for everyone.”

The reissuing of this book almost fifty years after its first publication squares perfectly with Vogel’s view that the text is a perpetual rough draft. He intended for the resource to endure through all modes of society, from the repressive to the post-revolutionary. For as long as power structures remain, so will the need for subversion.

Film as a Subversive Art is available to pre-order from Film Desk Books.