In 1923, just 24 hours before its debut at the notorious Paris Dada soirée, Man Ray improvised his first film, Le Retour à la raison. Given the impossibly fast production timeline, the American-born visual artist mostly relied on an experimental method that had recently preoccupied his still photography: photograms, or camera-less compositions made by placing objects onto photographic paper and exposing them to light. This technique became so commonly associated with the artist that they are also known as “rayographs.” This year, Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan's atmospheric rock band, SQÜRL, semi-improvised an original score to accompany a 4K restoration of Man Ray’s four films from the 1920s, undertaken in celebration of the centenary of the artist’s cinematic practice.

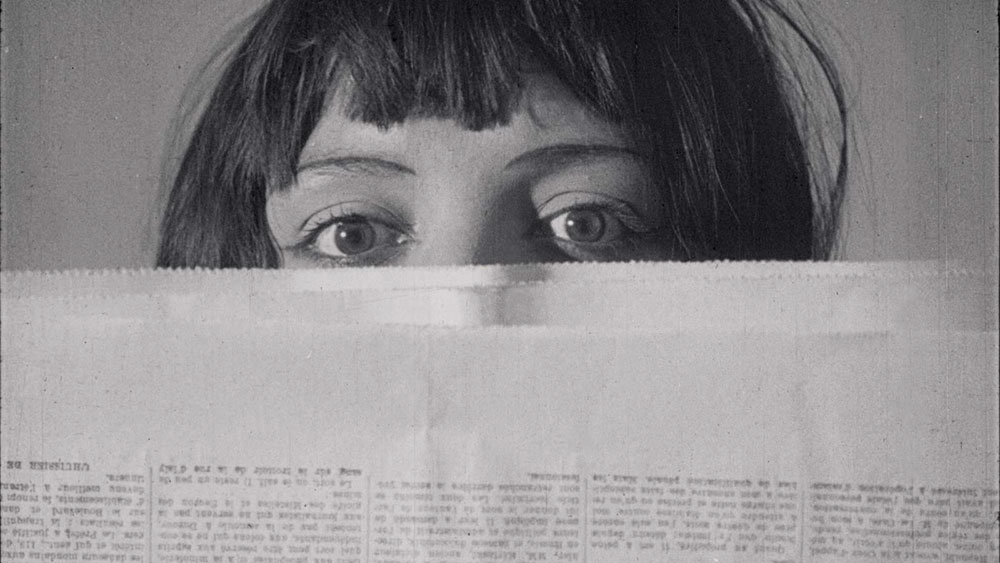

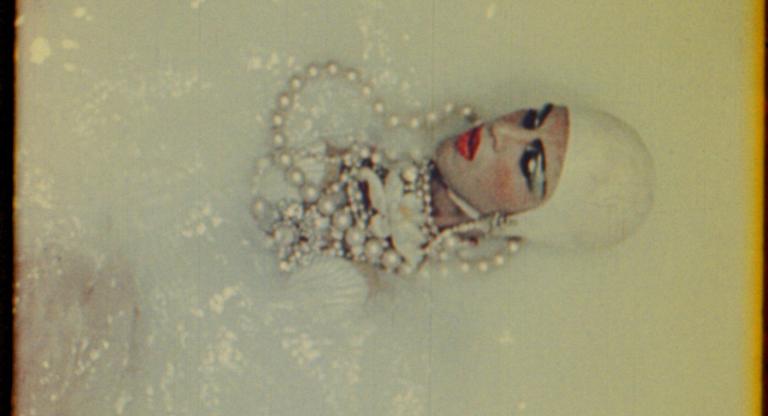

Collectively presented under the title Return to Reason, these silent pictures—Le Retour à la raison (1923, 3 minutes), Emak Bakia (1926, 19 minutes), L‘Étoile de mer (1928, 17 minutes) and Les Mystères du château de dé (1929, 27 minutes)—were dubbed “cinépoèmes” for their fragmentary and experimental essence that delved into the subconscious mind. Man Ray’s friends, also notable personalities in the Parisian avant-garde—Jacques-André Boiffard, Robert Desnos, Alice Prin (Kiki de Montparnasse), and Jacques Rigaut—enter the films as mysteriously as they exit them. Behind diffused glass or in soft focus, they drive cars to abandoned villas while a looming bass drum crescendos, dance to electric guitar riffs, and throw dice during hypnotic synth loops. Though Man Ray did sketch loose yet enigmatic narratives for the later three films, they are governed by an uninhibited dream logic that is mirrored by the psychedelic automatism of SQÜRL’s score.

For those of us who have watched these fuzzy, flickering films before, the restoration work is astonishing. The assiduous conservation process, which involved sourcing original prints from La Cinémathèque française, the Centre Pompidou, the Library of Congress, the French CNC, and Cineteca di Bologna, has reinstated Man Ray’s vision with extraordinary clarity. It serves as a reminder that his imagery was not a product of after effects, but instead required him to experiment in camera. And experiment he did: making rayograph sequences with pins; cleverly reversing a shot of a woman diving into a pool in Les Mystères du château de dé; oscillating between negatives and positives; playing with stop motion and double exposures; even sprinkling salt and pepper directly onto the film of Le Retour à la raison.

Pedantic purists might be bothered by how dramatically SQÜRL’s often angsty accompaniment differs from what Man Ray originally suggested for the films. For Emak Bakia, “any collection of old jazz will do,” and he preferred “French popular music” for L‘Étoile de mer. Le Retour à la raison is typically screened in silence, as he produced the film so quickly that he was not able to arrange a soundtrack. But SQÜRL’s intention was not to historicize these films or preserve their original viewing experiences as much as it was to extend their current sphere of reference. The duo’s interpretation highlights Dada and Surrealism’s relevance 100 years later as enduring touchpoints for the avant-garde, namely post-psychedelic rock and contemporary independent cinema.

Return to Reason: Short Films by Man Ray starts Friday, June 7, at the Roxie.

Previously:

“Return to Reason: Short Films by Man Ray” screens this evening, October 8, and on October 10, at the New York Film Festival, the North American premiere of new digital restorations. The screenings will be followed by conversations with score composers Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan.