Writer director Adoor Gopalakrishnan is a pioneer of the new wave of Malayalam cinema and has gone on to become one of the most well known and celebrated filmmakers associated with “Parallel Cinema” outside of India. His feature film debut, Swayamvarm (1972), made after a series of documentaries in the mid to late 1960s, heralded the arrival of an important voice in Indian cinema speaking in the Malayalam language (one of the country’s classical languages). With films such as Elippathayam (The Rat Trap) (1981), Mukhamukham (Face to Face) (1984), Mathilukal (The Walls) (1990), Vidheyan (The Servile) (1994), and Nizhalkuthu (Shadow Kill) (2002), Gopalakrishnan created a complex and mature body of work, one that was unafraid to show the endemic forces facing a changing society and the darker, more squalid side of life in his native Kerala province. His is a vision of personal, familial, political, and social struggle often informed by communism (the Communist party is one of two major parties in Kerala), and its place in the region’s history, that highlights the tensions and affinities between tradition and radicalism. Gopalakrishnan masterfully presents these sometimes disjunctive, sometimes complementary poles with austere elegance—thematically, formally, and structurally—in his 1995 film Kathapurushan (The Man of the Story).

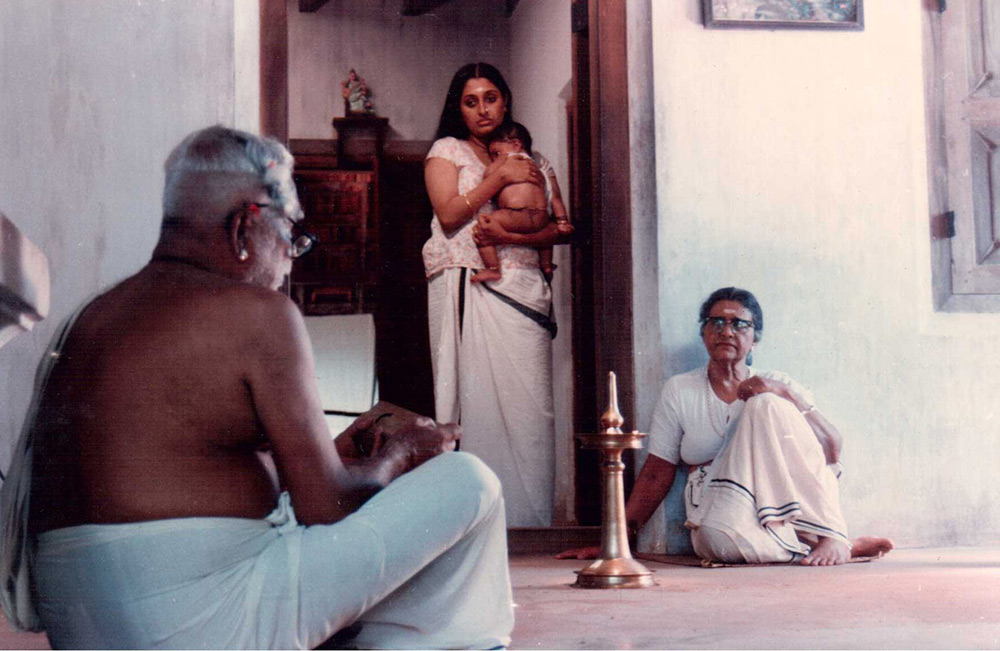

The film begins with a folk tale being told in direct address to the camera. The speaker’s framed in close up against a black backdrop as he recounts the meeting of a prince, his wife, and their young son with a hungry demon. From here, we move to the birth of the film’s protagonist, Kunjunni. His father leaves when he is born and the boy grows up on an estate with his mother and grandmother and Meenakshi, the daughter of a servant. The portion of the film devoted to Kunjunni’s boyhood comes to an end soon after the assasination of Gandhi. From here we see Kunjunni in college. He is now a communist, and after an attack on a police station, he is arrested and sent to jail. Years later, Kunjunni is released from prison. He finds Meenakshi and they marry and have a son. Eventually, he is approached by a former classmate for an interview about his earlier years of communist organizing. The journalist then helps Kunjunni publish his novel, but after its release it is quickly banned. Kunjunni, his wife, and his son read about the book’s fate and his impending arrest and, in much the same way the prince reacts to the demon in the folktale, they laugh.

Gopalakrishnan’s film is primarily concerned with tracing Kunjunni’s personal and political evolution with clarity, a choice emphasised and given shape by the allegorical folktale frame. While there are strong emotions signaled by the film’s dramatic developments, the overall effect of the film is similar to the later work of Robert Bresson. Its power is in its economy of staging, images, sounds, and narrative. Kathapurushan jumps forward in time when meaning calls for it—everything unessential left implied by the cut. The near abstract strain of the Bressonian approach is perhaps most clear when the police raid the printing press where Kunjunni is working in order to arrest him. The scene is a collection of fragments that are somehow, almost magically, united by understated sound design and our cumulative understanding of what’s happening. When the handcuffs are placed on Kunjunni’s wrists it’s difficult not to recall a similar feeling while watching L’Argent (1983).

The film was a co-production between Gopalakrishnan himself and the Japanese company NHK. The director’s longtime cinematographer, Mankada Ravi Varma, brings a subtly unnatural visual incisiveness (similar to their collaboration Nizahlkuthu seven years later) reminiscent of Nagisa Oshima to the film. Gopalakrishnan’s film is more gentle (the warmth radiating from Kunjunni’s guildless, smiling face) than the work of Oshima or Bresson, but his film is a likeminded testament to the restraint and precision of what Bresson called “cinematography” : a delicate balance between narrative action, meaning, sound, visual beauty, and formal radicality that’s able to achieve something simultaneously alien and human.

Kathapurushan shows in 35mm at Asia Society 2:15pm this afternoon in the series Parallel Days/Bollywood Nights.