Like its central character, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) abhors and reveres its own nature. At heart it’s a gothic horror film preoccupied with a famous pedigree. This stuffy adaptation comes alive only in deep shadows and violent outbursts and feels inert when mulling the philosophical implications of its source material or attempting to replicate Oscar Wilde’s famous quips. In fact, the film stops dead whenever Wilde’s mouthpiece, Lord Harry, a dandy of leisure played by George Sanders, embarks on a sassy promulgation concerning human nature. Such pontification served as the meat of the novel, but here it’s strained into a tedious warble. (This despite the ever-droll Sanders being perhaps the ideal movie actor [Charles Laughton also comes to mind] for Wilde’s quotable quotes.) Ironic that a work known for the brilliance of its language would inspire a film that only succeeds visually. The moral rot embodied in Gray’s portrait seeps out to create an atmosphere of dread in which violence is the foregone conclusion. As with a great horror film, we feel hurtled toward death from the opening minutes. The film ultimately fails as literary prestige picture but very nearly succeeds as portrait of a tortured murderer.

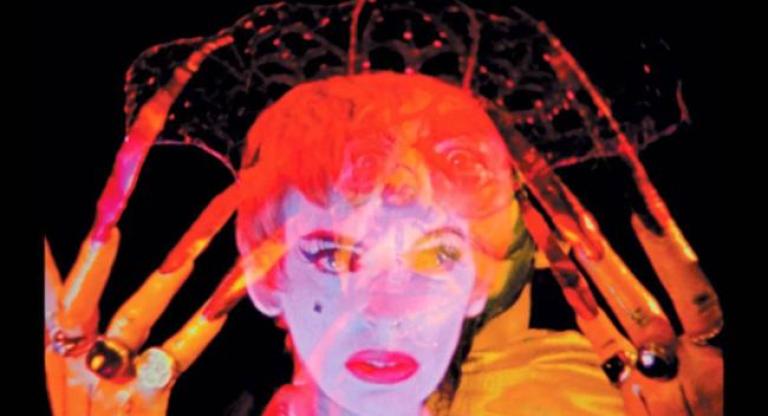

Those immune to the charms of Wildean zingers can instead enjoy in this adaptation — the seventh overall and first with sound — the unsettling pleasure of Hurd Hatfield’s cadaverous face. As the title character, Hatfield rigidly stalks the frame with an immobile expression and glassy line deliveries. He is a pathetic monster from his first moments onscreen, a presence as lacking in visible humanity as Nosferatu or Peter Lorre’s child murderer. To paraphrase Robert Downey Jr., Hatfield goes “full creep.” While an intrusive narration provides updates on Gray’s decaying state of mind, his emptiness is more efficiently written on Hatfield’s lifeless gaze. The blunt-force intensity of his expression belies the subtlety of Wilde’s “philosophical novel,” but provides the film’s true center. When the filmmakers tune into Hatfield’s frequency with noir-ish, Oscar-winning lighting schemes, a powerful film threatens to emerge from the foppish muddle. Though it can’t redeem the film’s misbegotten literary varnish, Hatfield’s spooky performance provides enough thrills to justify the experience.