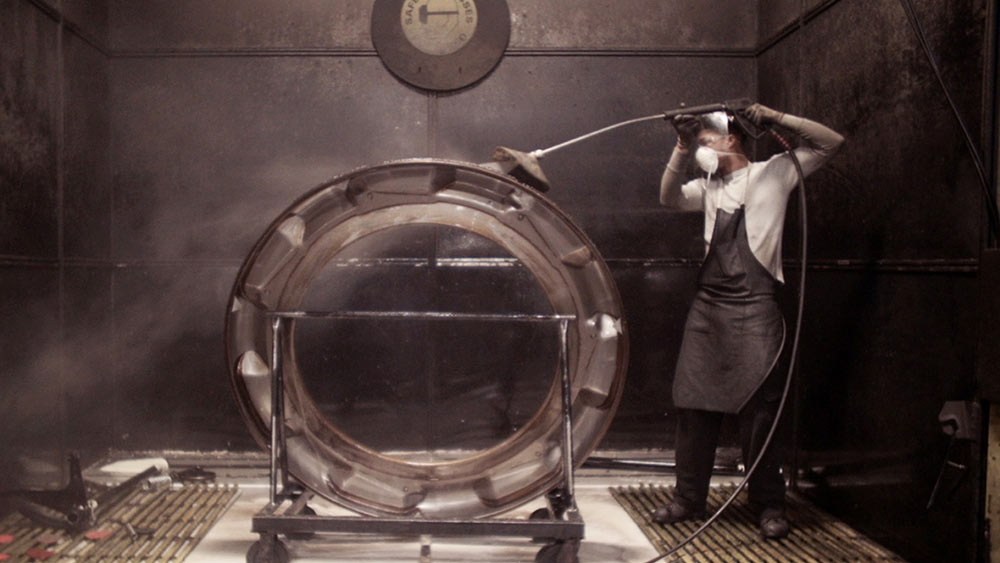

For eight hours, the subjects of Kevin Jerome Everson’s mammoth documentary Park Lanes bend, join, and paint lengths of metal until their contributions coalesce into state-of-the-art bowling alley equipment sold by their employer, QubicaAMF Worldwide. Before Everson’s sedate camera, dozens of mostly POC employees perform dozens of tasks during dozens of lengthy vignettes, in which repetition offers a pleasant clarity with regards to the work’s purpose. We familiarize ourselves with the work, perhaps imagining ourselves doing it. We recall pieces of equipment last seen in hour two as they reemerge in hour six for a new paint job. The film offers a surplus of visual pleasure and space for contemplation of one’s own role in the workforce. The experience is profound, often beautiful and never tedious.

There is no shortage of infotainment concerned with manufacturing, the most well-known example being the Canadian series How It’s Made, a creepily dehumanized menagerie of gizmos and widgets originally broadcast in the States on the Science Channel but currently available in microdoses on YouTube alongside countless other slick paeans to industrial engineering. But the intimidating accumulation of Everson’s footage and his refusal to interrupt the workday’s relentless passage foreground the relationship between these toilers and their machines, and more crucially, the obscured connections between spectator and subject. The film offers many of the same pleasures as various genres of internet video (“oddly satisfying” clips, livestreams, slow TV) but emphasizes the role of human hands and backs at work in exchange for pay.

These are the “good jobs” on perpetual offer during campaign visits at tile-floored diners in swing districts. Meanwhile, union membership in manufacturing has been halved since 2000 and automation continues to devour these positions with no end in sight. Without interviews or editorial intervention, Everson’s approach has no place for this context, and thus captures a nearly utopian vision of a dignified workforce toiling in the construction of useful, recognizable products. These workers only acknowledge the camera when sheepishly asking Everson to move out of the way or teasing coworkers about their “big break,” so we’re left contemplating their wages, benefits, job security, and relationship to management. But these jobs do indeed appear to the untrained eye as “good” ones, the type that engage the body and the mind toward legible ends without degrading either too devastatingly. The type of jobs that good liberals want for their “community” but not for their own children. There’s no sign of hurry or surveillance or curtailed breaks or mandatory overtime, though we can’t be sure these men and women are free from such hazards. One of the horrible pleasures of the film is imagining Jeff Bezos as one’s seatmate, writhing in audible discomfort at the inefficiencies of the factory’s process. These workers are of course alienated from their labor, but such is the barbarism of the advancing state of American work that we consider them infinitely better off than the Uber driver, Tyson meat packer, or Amazon fulfilment associate.

Park Lanes is streaming on the Criterion Channel

Still: Park Lanes, Kevin Jerome Everson, 2015; © Kevin Jerome Everson: courtesy the artist; trilobite-arts DAC; Picture Palace Pictures