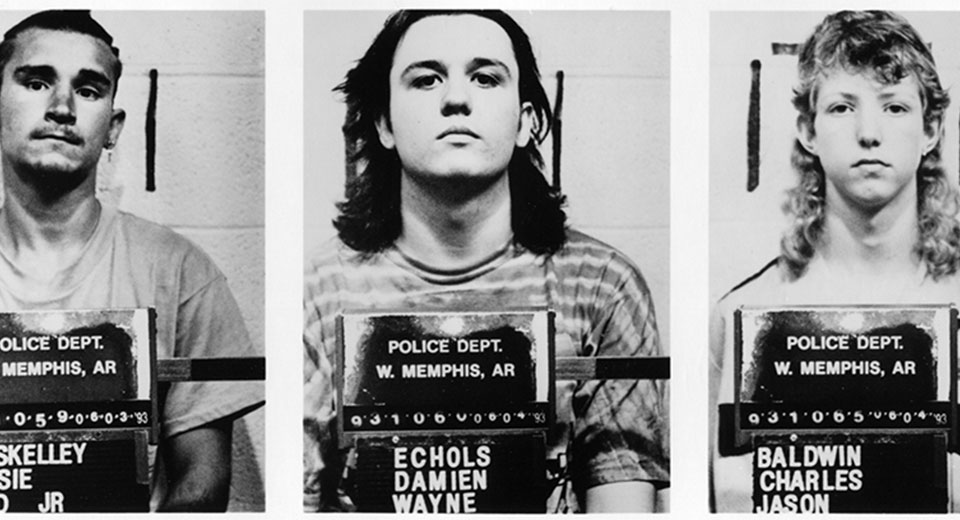

Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills , the 1996 HBO documentary, begins with footage of the police discovery of a particularly grisly scene: three young boys' mutilated bodies posed beside a stream not far from their small-town Arkansas homes. As the following news footage reveals, three local teenagers were almost immediately arrested for the murders. Jason Baldwin, Damien Echols, and Jessie Misskelly, the so-called "West Memphis Three," were high school students who liked listening to Metallica, reading about Aleister Crowley, and daydreaming about their girlfriends, interests which, despite what the prosecutors claim, are shown to be quite average to the white, working class community in which they and the three young victims lived. Stumped by the sophisticated, bizarre crime scene and its disturbingly sexual nature, the West Memphis police and prosecutors turn to an explanation which seems absurd today but was widely accepted by American institutions at the time: a cult ritual performed by satanists, the signs of whose presence (vague graffiti, black nail polish, teenage malaise) were rampant in the area.

The state's lack of direct, physical, or scientific evidence contrasts with the film's role as evidence—not only of the West Memphis Three's guilt or innocence, but of the prejudices and fears that defined this era with devastating consequences for the many accused, particularly in marginalized or poor communities. As in Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky's previous film, Brother's Keeper (1992), when representatives of the justice system find themselves confronted with something other, a crime with signs they are unable to interpret, they turn to the least empowered members of their society for a scapegoat. In the case of Paradise Lost, the film came to play a significant—though not uncomplicated—role in its subjects' fate. A running theme throughout the eventual documentary trilogy is a parallel focus on another popular villain of the 1990s: the stepfather, specifically the victims' stepfathers, whose filmed behavior is often inappropriate or eccentric. In pointing to the danger in allowing prejudice to define a prosecutor's case, the filmmakers demonstrate the indispensable role of the media in such a prosecution and its success.

The film is followed by two sequels, Revelations, 2000 and Purgatory, 2011, which trace the case for the three young men’s innocence as it unfolds, as well as the enduring effects of the films themselves. Much like the newly-released Southwest of Salem—a documentary of a strikingly similar story, in which four lesbians are accused of extreme and bizarre sexual molestations as part of a witchcraft ritual—Paradise Lost assisted not only in the West Memphis Three's effective exoneration, but also in bringing about the end of the "satanic panic" era. Though we will likely never know who committed the child murders at Robin Hood Hills, the documentary is indispensable evidence against a criminal justice system subject to prejudice—an instance of successful intervention worth revisiting now.