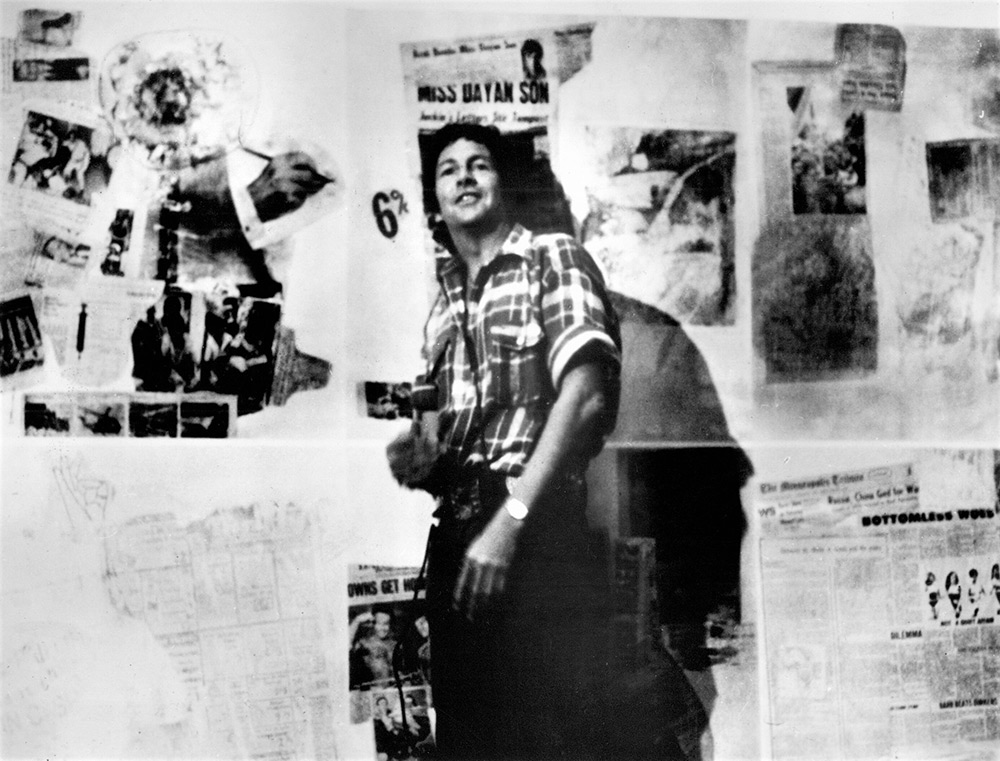

In 1972, documentarian Emile de Antonio made a film about the New York art scene. It was occasioned by the Met’s “New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940 - 1970” exhibition, which gathered works from artists such as Willem de Kooning and Helen Frankenthaler, among many more luminaries. Best known for political documentaries like In the Year of the Pig (1969) and Underground (1976), de Antonio’s Painters Painting showed a different facet of his personality, while still showcasing his unique strengths as an interviewer and image-maker. Presenting such artists as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg in as candid a manner as possible, and relying on the ingenious idea to shoot said artists in 16mm black-and-white while filming their art in 35mm color, Painters Painting not only offers a close study of the American artist, but of their art as well. Its power is both centripetal and centrifugal: it cues you in with its delicate black-and-white compositions before jolting you with the marvelous colors that defined—and perhaps continue to define—what American art is.

Much of Painters Painting’s visual wonder stems from Ed Emshwiller’s camerawork on the film. Seconds into de Antonio’s film, Emshwiller swivels out of a Frank Stella painting and lurches into a gallery featuring more of his work. The frame, focused on a white box lined with colorful geometric shapes, is not dissimilar to the sorts of frames present in much of Emshwiller’s cinema, which so often positions people in empty spaces and uses circular motions or spiral-like shapes to achieve a visual hypnosis of sorts. It’s not de Antonio’s intent to hypnotize with his documentary, so much as make the viewer incredibly aware of how striking or shocking the content of the paintings he gets up close and personal with is. This aggressive cinematography, totally distinct from the staid tableaux of more conventional art documentaries from the era, brings life to the paintings onscreen, as though each brushstroke is still settling and each glob of poured paint still running.

What becomes evident in de Antonio’s film is just how related each painting and sculpture he films is to their artist’s psyche, and how that psyche is a product of the social environment they were embedded in. He doesn’t just demonstrate the indexicality of a Pollock by showing how each brushstroke is the product of a violent arm jerk, but he relates that sudden motion to the commotion of a nation in flux; in fact, at some point, he notes that Abstract Expressionism stems from a certain mixture of anger, anxiety, and violence that is singularly American. Politics are unavoidable in the work of de Antonio because he was a man who lived and died by his own set of radical politics. That he would find the anger, disillusion, indifference, and hope of the United States in its so-called national art, then, is also to be expected. That his film brings out said feelings from long, unreserved interviews and precise cinematography is its genius. Whether dealing with art or war, de Antonio is aware that all of our nation’s ills stem from the same place: an insistence on a future for the few and a dismissal of the many’s present.

CONTOURS is a column by Saffron Maeve (and guests) examining films that thematize the world of visual art: painting, sculpture, illustration, and performance. Maeve also programs a screening series of the same name and premise at Paradise Theatre in Toronto.

Painters Painting screens this evening, October 14, at Light Industry on 16mm. The artist Amy Sillman will introduce the screening.