Wim Wenders tells us his first Yohji Yamamoto fashion experience was as a consumer, having bought a Yamamoto shirt and jacket that made Wenders feel “more me than before,” partly on account of the garments somehow seeming “new and old at the same time.” The movie Wenders later made about Yamamoto, and about himself, is like that too, being deftly stitched together from Hi8 video as well as 35mm celluloid, organized around a give-and-take between spontaneity and rumination, and impressively conversant with 2026 concerns for a film that was released in 1989.

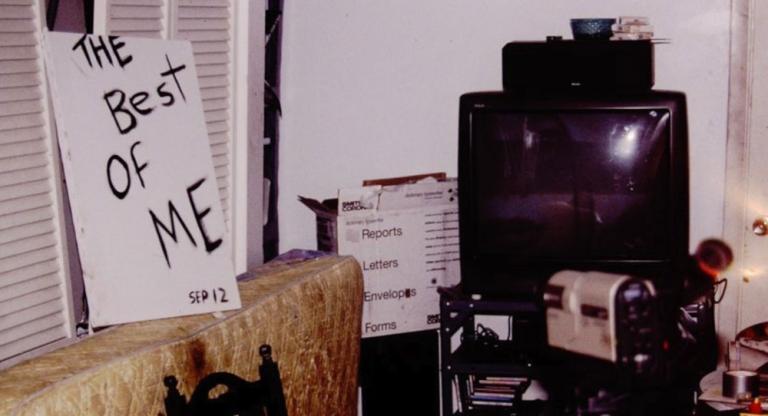

Before digital cinematography had a foothold in film culture, before social media even was possible, here was Wenders’s diaristic fashion documentary full of first-person narration, noting an algorithmic onslaught of images “multiplying at a hellish rate,” and, relatedly, that “we are creating an image of ourselves, we are attempting to resemble this image—is that what we call identity?” Rhetorical riff or not, it’s still worth asking: do the images we choose to inhabit, even when we don’t trust them, make us more us than before?

Commissioned by the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Notebook on Cities and Clothes let the director steer his proclaimed fashion skepticism into a casually cherishing kind of motion-picture philosophy. (Later, a similar invitation to come check out some architecturally interesting Tokyo toilets would yield Wenders’s Zen-friendly 2023 crowd-pleaser Perfect Days.) A couture designer famously influenced by utilitarian workwear, Yamamoto proves a worthy Wenders subject, although subject is too strong a word for a heady hangout film like this. See also how “cities” and “clothes” are big topics, but a “notebook” can remain a loosely held, scribbled-in thing. In one signature moment, Wenders dwells on Yamamoto dwelling on a photograph of Jean-Paul Sartre, compelled by the line of the collar in Sartre’s coat. In another, as Yamamoto disclaims resistance to the innate symmetry of the human form, and preference for asymmetry in his own creative compositions, the camera cordially pans, pushing him over to one side of its frame.

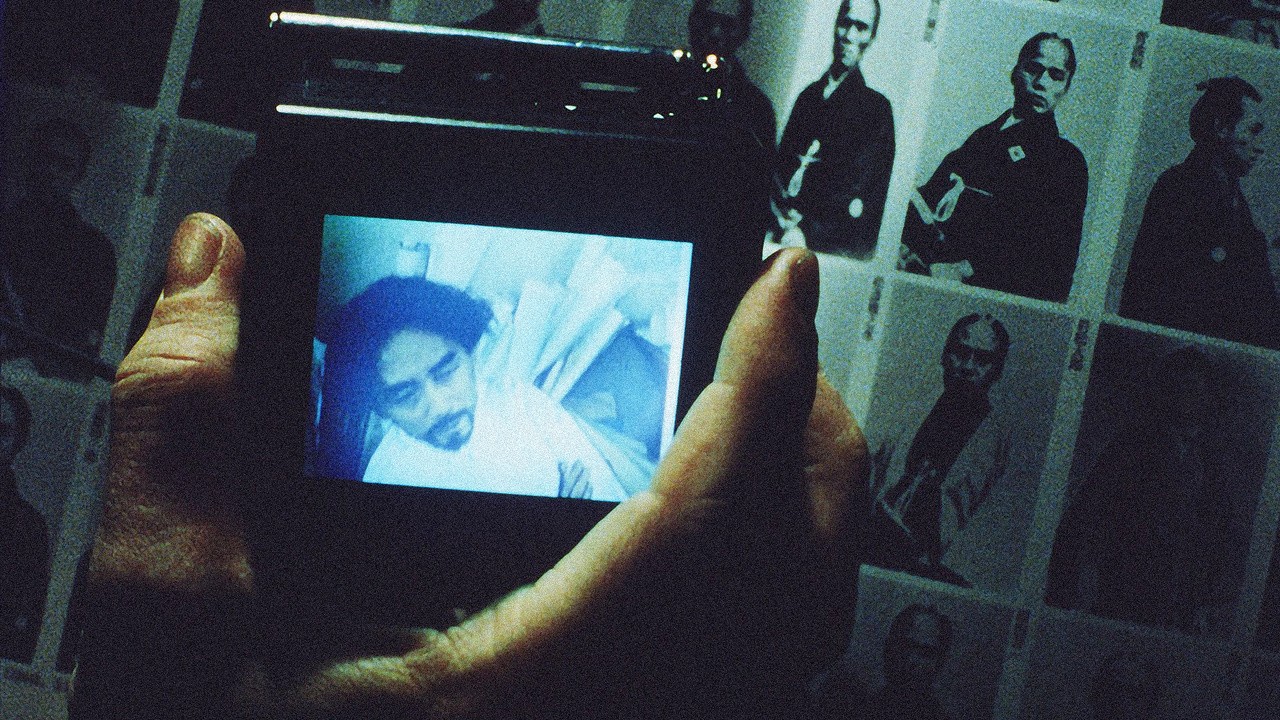

By seeking, as Wenders puts it, “the essence of a thing in the process of fabricating it,” he arrives at a substrate that fashion and film have in common: in Paris, while gazing through the windshield of a moving car whose passenger seat carries a video monitor displaying similar footage from Tokyo, we hear Yamamoto say what he thinks after all would really be nice: “If I could design time.”

Notebook on Cities and Clothes screens next Monday, January 26, at the Balboa Theater.