In the six years after the advent of sound film and before the enforcement of the Hays Code, American cinema explored themes and subject matter it would not touch again for at least three decades: criminality, vulgarity, and sexuality of various stripes were all proffered, often quite candidly. The screen was a window onto the real concerns and curiosities, insights and prejudices, of the era. That window would soon slam shut, placing a thick pane of warped glass between the American public and the aspects of their lives that the state-censored cinema was still permitted to depict.

Today, these films hold the tragic promise of a lost art, a path not taken. They can appear unstuck in time, vibrating at the otherworldly frequency of what might have been. In the words of the filmmaker and programmer Adam Piron, they present “a reconfiguration of America toward something more honest in terms of how it saw itself, rather than something it traditionally aspired towards.” Though certain subjects eventually returned to the popular cinema with some semblance of their pre-Code integrity, some never did.

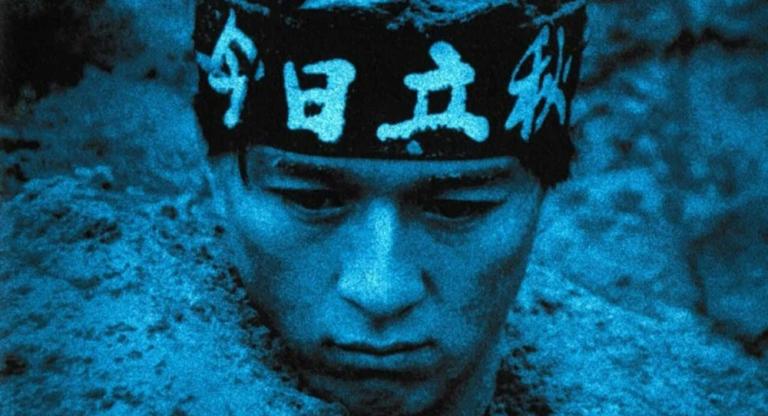

Piron’s current series at Metrograph, “Save the Man: Pre-Code Hollywood’s Native America,” includes four rarely seen films addressing the situation of Native Americans—not as broadly drawn fodder for bellicose Westerns or as noble relics of a former greatness, but as contemporary subjects responding to the world in which they find themselves, a vanishingly rare approach in studio films to this day. Their representations are deeply imperfect, and certain aspects may be altogether disqualifying, but as documents of social history they are essential.

I spoke with Piron about the series as well as his own short video, Dau:añcut (Moving Along Image) (2023), which will screen in the Currents slate of the upcoming New York Film Festival. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Maxwell Paparella: How did you begin to encounter these works, and were you surprised to find them dealing with these themes with such nuance in the 1930s?

Adam Piron: It started at the beginning of the pandemic. They were advertising one of those Warner Archive sales, and I was just going through the titles. One of my interests is the Indigenous image in film—films directed by Indigenous folks, but also the history of how Indigenous people have appeared and shown up in films, whether it's been somebody playing an Indigenous person, and having that be part of this amalgamation of identity that happens, or if it's Indigenous folks. So I came across some of these titles there. I wanted to check them out because of everything that's been going on with Warner. These are titles that are just gonna get buried, or it's stuff that they're never gonna release. With studios getting more progressive, to some extent, around identity politics, there's things that they would prefer nobody remembers. I want to remember them, and you can't let people forget about it.

I also came across this book during the pandemic called “Injuns”: Native Americans in the Movies, by Edward Bascombe. He goes into the whole history, from literature to film, of how Indigenous people, specifically Native Americans, have been perceived and how their image has been shaped. There were a very interesting few paragraphs on the 1930s. He says, ‘Well, there wasn't that much that was significant in the pre-Code era.’ After seeing these films, I really disagree with that.

MP: Are there any other films that you would have liked to include in the program?

AP: There were two other films that I was really hoping we could show, and we just weren't able to. The print for one of them was in Russia. It’s this film called Whoopee! [1930], an Eddie Cantor film. It's the first film Busby Berkeley choreographed. And then there's this other film with Clara Clara Bow called Call Her Savage [1932] that MoMA did a restoration of a couple years ago. They explore this trope of mixed Indigenous people who are half-white being torn between two worlds, but they end in weirdly opposite ways. In Whoopee! this supposed half-Native guy falls in love with this white woman, and then at the very end the big reveal is his Indigenous parents are like, Oh, you're actually adopted. So it's OK you guys are together.

In Call Her Savage, there's this whole thing of this woman being very short-tempered, and it leads to a number of problems in their life. And then the big reveal at the end is that, Oh, well, your mom had an affair with a Native guy on the ranch that you grew up on, so you're actually part Native. That explains why you're so hot-headed and impulsive. I think this period was really looking at a lot of those stereotypes and playing into some of them, but then you also have things like Eskimo [1933] or Massacre [1934].

MP: Let's talk about Massacre a bit. I was pretty blown away by it.

AP: Massacre is an incredible film in terms of how specific it is to certain Native historical points. It’s a major milestone of the Native image, or the Native character. The first images of Indigenous people in film were show Indians from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in that Edison film [Buffalo Bill, 1894]. And so it's kind of crazy that this film is about a show Indian who demands better pay. He clearly runs the show; he's a star and knows it. But [it’s] also [about] him going back to the reservation, seeing how it's been run and how there are these corrupt government officials that are exploiting everybody. It’s weird how much of that film clearly knew what it was talking about, a film that's almost 100 years old at this point.

There was this point in Hollywood history where they were less about looking at the past and more about what was actually going on. 1924 was the official end of the Indian Wars, and it's ironically also when Native Americans were allowed to become American citizens. As the silent period ended, there was a whole new concern around social issues. As they were looking to the present, there were a lot of questions around Native Americans, who are arguably more American than America itself. So where do they fit into all of this, especially now that they're citizens, so we can't shoot them anymore?

MP: Massacre is doing something sophisticated and kind of cunning, right from the title, which sounds like a different kind of cowboy film than the one we find here. Even when you're introduced to the character of Joe, he's speaking this halting “Indian English” to the autograph-seekers in the stands, which is also what the audience expects to hear. And then he goes backstage and turns into a very urbane, Anglified smoothtalker.

AP: He literally says, “Take this junk off of me.” The whole thing is all performative.

MP: In the next scene, his white girlfriend has created a one-room museum of Native American artifacts to show him. It struck me that both of these structures of representation, the performative and the museological, are still the dominant ways that a white audience is introduced to Indigenous cultures.

AP: It's this room filled with paraphernalia, and he's one more piece of that, so to speak. The thing that's interesting about it, too, is that the film really calls him out for playing into that. It's probing even the idea of Wild West shows: Why do you want to see this? It really digs down into this white American urge or propensity to collect things, especially when it comes to Indigeneity. But then, at the same time, there is the exchange of [his performance]. There's been a lot of writing about this, how [for] Native performers in early film, or in Wild West shows, part of it was a very uneasy exchange of people being exploited, but then also playing into that, being able to flip that to their own advantage to get certain things. It's interesting to see that in the film, where that happens in both a literal and metaphorical sense.

MP: It seems like these films were each in their own way negotiating some kind of relationship with what the audience expects of the Native subject. I was looking at the poster for Eskimo, which has Lotus Long painted very buxom, barely contained by folds of fur and ice. People who went into the theater for that were probably in for a surprise.

AP: When you look at the time, there's the idea that, after switching to sound, a third of the theaters in the country had shut down and audiences were down by 50%. So I think they were willing to try anything to get people back into the theaters. Upon its initial release, Eskimo, under that title, didn't do so well. A couple of weeks later, they released it somewhere else under the name Eskimo Wife-Traders. The movie has nothing to do with that, but they're selling some sex component of it, which the film doesn't have at all.

MP: In your program notes, you make mention of the pre-Code era’s “affinity for breaking on-screen taboos.” I wonder how much that had a specific political valence, or how much of it was intended to flatter the savvy of the audience and give everyone something to chew on.

In pre-Code films there’s this smaller trend of Indigenous-centered stories or films dealing with Indigeneity in, for the time, a very nuanced way, as far as white white America probably saw it. They are all very openly questioning the idea of America versus the people that were already here. I find it fascinating that people were just doing this and that there was somewhat of an audience for it. They kept making these films.

Obviously they mix a little bit of sex in there. You see that with Massacre where he has this white girlfriend and these white women fawn over him when he has his shirt off. I think maybe the taboo—in the same way that you have something like The Public Enemy [1931] or Scarface [1932]—is also glorifying the criminal versus American law. It's very much in play with a lot of the pre-Code stuff of questioning American ideals and also reveling in things that are perceived as being in opposition to it.

MP: Although at the end Massacre turns really decisively toward reform, of course. He leaves his job in the sideshow to work in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He has that big soapbox diatribe against burning the courthouse.

AP: I think that shows the limits of even the pre-Code stuff. FDR was in office then, and the New Deal was starting to kick in. They're very careful in that film to not indict the federal government. It's like, Oh, no, it was a corrupt individual that was doing all this stuff, but the system works. For me, that’s the idea behind the name of the series, “Save the Man.” That phrase that was coined [in 1892, by Captain Richard Henry Pratt], “Kill the Indian, save the man,” was centered on forcibly assimilating Native people into white society. In the conclusion of Massacre, the idea is, Well, Native Americans should just become like us; they should hold the same ideals as Americans. And some folks do, and that's fine. But it's missing the whole point.

MP: A lot of the Native characters in these films, including Massacre, are played by white actors who have darkened their complexions with makeup, or in the case of Laughing Boy (1934), they're played by Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

AP: Eskimo is interesting, because the lead character is played by an Alaskan Native actor. His name is Ray Mala. He was working in the studio system as a cameraman. He was in some smaller B serial things, and then he went back to the camera department. He worked on a Hitchcock film [Shadow of a Doubt, 1943]. The majority of that film is in Inuit language, so they had to get folks that could speak it, and they were shooting in Alaska. His [on-screen] wife, [Lotus Long], was Japanese and Native Hawaiian. I think W. S. Van Dyke, the director, was going for something that he saw as authentic—while still playing into a lot of stereotypes, obviously.

MP: The series, in presenting films that do and don’t cast Native actors for Native roles side by side, seems to push us to consider questions other than the rote matter of representation, which are mostly the grounds on which we hear these discussions playing out today.

AP: I would agree with that to a certain extent. I don’t want to poo-poo [the concern for representation], but it's interesting that Hollywood at the time got this one component right. It put these characters in a modern context, and it's looking at their reality, or an interpretation of their reality at the time [and asking,] How does it fit within the larger kind of questions about the country? You look back on it, and you're like, It's the 1930s. They wouldn't have cast Native people in those roles, which is partially true. But then you look at something like Eskimo and you're like, But they also did. The films are this weird exception, but there's also an exception within them. To me, it's just fascinating that this is something that happened and that it was consistent throughout the pre-Code era.

And it's interesting, too, that there's not really been a major studio film centered on the existence of Native people within a contemporary time period [since then]. I guess it's easier for studios to sell Dances with Wolves [1990] or Apocalypto [2006]. Hollywood was doing this at one point, and then the pre-Code era slid away. And then you have Stagecoach in ’39, which revived the Western in a big way and set everything up for the ’40s and ’50s. There was this brief period where it was like, Oh, you guys could have just gone a little bit further. Which is why everybody loves the pre-Code era: the creative tragedy of the Code being enforced. We're just starting to get back around to stuff that's thematically and maybe even formally a little bit more bold. It's the big What if? What if they kept going for a few more years, what would things have looked like if they were already doing this sort of stuff?

MP: Do you attribute that break to the imposition of the Code, or to the resurgent popularity of a more hackneyed Western race-war narrative?

AP: Probably both. It's like with anything in film: it's political. But I think in particular when you have the image of a Native person it's going to be political, when you go to the foundations of the moving image itself. The Code tried to regulate and censor things, [which worked against] these sorts of films that question and indict the nation on a historical and present prejudice. I just don't see how something like that would have stood [after the Code was introduced]. A lot of the pre-Code stuff was tapping into things that we’re just starting to normalize now within popular culture.

With Westerns, they have to shoot at somebody, either us or Mexicans. That's how it usually is. It's something that I think has always been within film, it always kind of creeps back in. Once you get to the ’60s and the ’70s, there's a point where Westerns start sympathizing a lot more with Native folks. And I think part of that has to do with Vietnam going on. Natives become this cipher for the Vietnamese. People are questioning the war but also tying that war back to these foundational conflicts that happened within the country.

MP: W. S. Van Dyke is represented by two films, half the program. And this was Cecil B. DeMille’s third adaptation of The Squaw Man (1931), the first of which had been his debut feature (and the first film shot on the land that would eventually be known as Hollywood). What was it, do you think, that kept these white directors coming back to Native subjects?

AP: DeMille comes from that generation of directors in which it wasn't uncommon to revisit silent films that they had done, and just adapt them for sound. I think there's also a sort of natural inclination with a certain type of director—whether it's him or whether it's Coppola revisiting Apocalypse Now [1979] for the sixth time or whatever—this idea of retooling it. There were a lot of Indigenous performers in Hollywood who would be background actors or cultural consultants or things like that. DeMille had this film called North West Mounted Police [1940]. It’s debated whether this was a publicity stunt for the film or if it was in earnest, but he and a number of these actors tried to found an actual tribe as a political entity called the DeMille Indians.

DeMille is one—I think a lot of people would [include] Ford or Capra—of the American directors. It's hard to see that guy coming out of any other national cinema because so much of his work is tied to these foundational things within the idea of America. [The Squaw Man] is about a European under misbegotten circumstances who falls in love with a Native woman and has a kid, and the whole drama is essentially around if they will raise the kid Native or white. One could take that as a metaphor for the country itself. So maybe it’s DeMille playing with that, or maybe he's just going for something that's easy for him.

Van Dyke has a whole history of doing these exotic adventure films. These two films definitely play into that. He did another one set in Tahiti called The Pagan [1929] that also has Lotus Long in it. He's very much of that time of the exotification of these locales that are seen as the last frontier for people to go now that everything was colonized or mapped out. So that was definitely his bag: selling that type of film and selling that imagery.

And then with Massacre, that's by Alan Crosland, who also did The Jazz Singer [1927]. The Native representation in Massacre is very interesting, and progressive for the time, but the Black representation is particularly egregious. I mean, this guy directed The Jazz Singer, so . . . . I'm not super familiar with the rest of Crosland’s work, but it's interesting to see that race, whether it's probing it or exploiting it, is something that pops up in his filmmaking.

MP: I also wanted to take the opportunity to congratulate you on the inclusion of your own video, Dau:añcut (Moving Along Image) [2023], at the upcoming New York Film Festival. It explores the conflicted reactions of a Native American man— I think a relative of yours: is that right?

AP: Yeah, he's one of my cousins.

MP: —to a tattoo of his grandfather's likeness, which he’s seen online on the bicep of a Ukrainian resistance fighter. How did you become aware of the tattoo?

AP: We had another cousin who was looking to get a tattoo, and he was looking through these online tattoo galleries and came across it. For a while it was a bit of a joke: What if there was a Native guy that got a Ukrainian grandfather tattooed on his arm? But after you laugh about it there's a moment where you're like, Wait, this is really weird. How did this guy get this image? Because it wasn't available online. And so there's that question, but then it's also like, Well, who is this guy? What are his intentions? I can speak for myself; I can't necessarily speak for my cousin. But for me it wasn't so much a thing of feeling violated, but it was just kind of weird that this image is out there, and you don't have control over it. I think it taps into a larger question of images of Indigenous people and how they're objectified. They become a thing that you put on you, or you put on a t-shirt or whatever. The film is more about asking questions, rather than getting answers that I know we're not gonna get.

MP: And then you braid that in with the relationship between military culture and the warrior traditions of Native American nations and tribes.

AP: The base that a lot of that footage is from is called Fort Sill. It's a base near where our tribe’s land is and where our community is, but it was originally founded as a fort [in the course of] westward expansion and colonization. There's a fair amount of people in my tribe that also serve [in the military], and Native Americans serve at the highest rate of any [ethnic group] in the U.S. My cousin—we don't say that [in the video], but he was a Marine. My great-great grandparents were put onto a reservation [by] the armed forces. So it's also wondering, Well, what did they think about this?, in terms of their grandchildren serving in World War II and Korea and Vietnam.

The TikTok stuff was the last component to come through. If you're a government worker, they don't allow TikTok on your phone, but there’s a whole military subculture on TikTok called #miltok. I'm not going to be able to go onto that base and film anything that seems remotely authentic. So if these people are posting about their lives and their existence in there as they're living it, I don't know how I'd be able to come up with something better than that, or something that seems more true. You think of a lot of those folks, too. They're probably pretty young. I don't know how much they’ve thought a lot of this stuff out. Do they even know the history of the place that they're in as a fort? Why are they on a military base that's in the middle of the country, in Oklahoma, [rather than on] the coast? I think it's just leaving [the video] open for that, this never-ending conflict that this country seems to thrive on. That’s the thing that keeps the shark going forward.

“Save the Man: Pre-Code Hollywood’s Native America” runs September 22–October 1 at Metrograph, with all titles shown on celluloid. The programmer, Adam Piron, will be in attendance for introductions this weekend, September 22–24.