Released this past autumn, the music video for “Working for the Knife,” the musician Mitski’s first single from her new album Laurel Hell, drew to mind a series of questions posed by Douglas Crimp, writing in Artforum on a work by Merce Cunningham in 2008: “Does the dance consist only of the obviously choreographed, technically skilled movement? Is the dancer running off the stage still dancing? Is the dancer stretching or wrapping herself in a blanket right in front of your eyes something that you’re not meant to notice? How could you not notice?”

“Working for the Knife,” the video, begins with a frenetic, foreboding march toward The Egg, a performing arts venue in Albany’s Empire State Plaza whose grand inverted dome architecture evokes the science-fictional. Sound designer Joanna Fang provides an ominous murk and the sharp clacking of Mitski’s cowboy boots, and cinematographer Ashley Connor, Anger’s frequent collaborator, supplies a staccato, rapid-fire rack-focus that places the video in a slow, surreal, and subjective register. It’s a full minute and twenty seconds before the track actually begins, as Mitski reaches the interior of The Egg and walks out on stage. Mitski’s performance, as directed by Anger, intentionally explores the boundaries of performative identity and authentic sincerity, manufactured poise and creative catharsis.

“Working for the Knife,” the song, begins: I cry at the start of every movie / I guess cause I wish that I was making things too / but I’m working for the knife. The video reaches its peak after the song ends, and Mitski performs a heavily physical freak-out on the auditorium’s empty stage, an intimate and unnervingly corporeal mime of Denis Lavant’s “Rhythm of the Night”–scored acrobatics at the end of Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (1999).

The sense of authorship of a music video is typically reserved for the musical artist and the director. In this case it felt especially crucial to Anger to extend that ownership to her principal collaborators. The song, about finding your creative self inextricably knotted with the more destructive elements of art and commerce, struck a chord with everyone on the crew. The video’s final moments became a sort of ritual, a transference of catharsis, from one crew member to the next; a way to shake up the doubts and frustrations they had been feeling in their creative careers.

After the video was released, Anger gathered several of these crew members—cinematographer Ashley Connor, choreographer and movement artist Monica Mirabile, Foley artist and sound designer Joanna Fang, and editor Chris Osborn—to talk about the joyful, collective process of creating “Working for the Knife.” The crew began by discussing where they were creatively and professionally when Anger asked them to work on the video.

All photos by Lucas Carpenter. Above: stylist Tiffani Williams and Mitski.

Monica Mirabile, movement director: I had also worked on Zia’s videos for “Geyser” and “Washing Machine Heart” and choreographed Mitski’s last live tour. Last winter we were at a party when Mitski sent Zia “Working for the Knife,” and we sat out in my car and listened to the song for the first time.

We discussed the idea of an artist and their outside creative forces; the work vs. the workability. That overproduction of yourself never leads to anything that you can tangibly measure.

Zia Anger, director: We all have to work with and for forces that we don’t necessarily like.

MM: The experience described in the song is not an unfamiliar one. We tried to process what it means to be an artist working for an institution that you are, at the same time, trying to change for the better.

Ironically one of those aspects of commercial art-making that always seems unreachable is having a support system, but within the making of this video—the friendship and joyful collaboration involved—that was actually present.

ZA: I felt that unless I could get everyone who had ever shown up for me together for this video, I would be participating in the same cycles of damage and harm that the song and the choreography was speaking against.

Ashley Connor, director of photography: The video was a collaboration of people who give themselves fully to their craft and have suffered or compromised for it—for me, I had just gotten off of a huge commercial project that was creatively confusing, but to come from that to this song and these people—it was such a pure process, which is so rare when we’re all at a place in our careers where we work for hire a lot and things feel very out of control.

Chris Osborn, editor: Between this and our last collaboration I had been taking editing work just to make ends meet, and when I got the song I felt very affected and moved by it; I was burned out and hated the work that I was doing.

Joanna Fang, sound designer: I had just quit a job and moved across the country. When Chris reached out to me I thought, This can be a vehicle for my own frustrations. Watching Mitski slam her fists against the stage—it can be very meditative.

MM: Because we had begun discussing our collaboration so early in the process we are able to spend a lot of time working on the movement and the narrative of the movement. Typically you don’t get that amount of time; you get like a day. We would meet at each other’s houses and talk and move around and get really excited over that; and then in addition to that we got to work with Mitski for a whole week.

ZA: There’s never going to be a lot of money in music videos so our idea behind this was, let’s try to get something other than monetary gain out of this—let’s define and refine our process as collaborators.

MM: Which is a luxury that usually isn’t afforded; the luxury to develop your practice and collaboration within the preparation process.

We talked about how it shouldn’t feel like a performance; it had to feel like a ritual, like something that [the viewer] and Mitski are going through, spiritually. It has to feel real; if it’s just playing a game then it doesn’t matter. It can be playful, but it’s not a toy. It’s one of the things I love about working with Mitski, too—I don’t think anything is haphazard to her. She goes deep in. She takes both emotional and physical risks, and wants to embody it, which is dreamy.

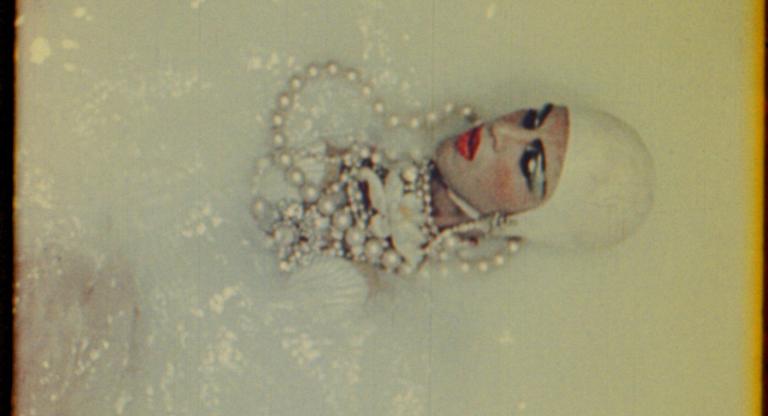

ZA: And by real, I mean not a one-to-one truth. What I’m always looking for in my work, and what I think Monica really aligns with, is the idea of achieving something through performance that’s more real than reality. We start with this really specific goal in mind and that goal is a feeling, and then look for the tiniest gestures. The major reference that me, Monica, and Mitski all settled on was Denis Lavant in Beau Travail because it felt like—between his background in clowning, his ability to find truth in the most micro physical gestures, and the context of the narrative of that movie—that was what we were looking for.

MM: The idea in the first half of the music video is that she’s performing when she shouldn’t be performing—prior to when she gets to the stage. The performativity is the everyday behavior of being an artist and musician in this position, as a product. It’s playful and clowning until she gets on the stage. On the stage is the reality, what we’re really trying to access, what we’re really trying to feel, but no one can see it. The clowning, the subversion, is that flip: performing every minute of every day unless she’s on the stage.

ZA: To emphasize and put a bow around that idea, it becomes the case where, when you’re an artist or performer embedded in that level of commerce, standing on that stage, that act of creation becomes all that you can do; that’s what she’s here on Earth to do. Just as Monica is here on Earth as a choreographer and movement artist, and I can only make moving images. And there’s this massive disillusionment that’s really hard to talk about, because, at the same time you’re so lucky to be on that stage, you know?

MM: You’re always going to be in that constant state of becoming, and there are all these barricades in the commodity of it all. And in the music video these play out in the form of the architecture [of The Egg]—the slanted wall, the stairs, the railing.

ZA: The biggest revelation we had was on the last day of rehearsals when we still had not figured out the ending. We knew what it had to be cinematically, but had no idea how to get there physically or emotionally. Narratively it was just that she needed to have a cathartic release, but there was so much fear; how do we get there? Do we choreograph it? Finally, on the last day, we had everyone speak on why we were making this, and we were all crying our eyes out, and then we all hugged and did our own version of it, what our catharsis would look like. I did mine, Monica did hers, and then Mitski did hers. I remember being like, “Okay, now lock that in. You need to remember this feeling, and then that’s it, that’s what we’re going to do.” And I think that’s the essence of Monica’s work and what she’s always thinking about, the somatic level of movement that’s down to the cellular level.

MM: It felt like Mitski really accessed this level of conjuring where her nervous system was affected. She was in tears and wanted to do it again. And I think that’s what makes this film so special; that it’s real. This wasn’t a performance; she really embodied it.

ZA: The first time I had felt like I achieved anything close to that in a music video was on “Your Best American Girl,” watching her just play guitar in front of this couple making out. I remember watching her and feeling like my heart has smashed into a million pieces. It was a totally manufactured situation, obviously, but I felt like we had reached or accessed something real. This was a very similar situation—despite the camera and the lights, I had the sense of like, Wow, this is so real.

AC: My practice has to do so much with my body, and on bigger union jobs I don’t get to camera operate. I want my operating to be corporeal, and I love dance. I’m trying to break an emotional barrier with the subject, the performer, and create a conversation with them. I want a camera on my shoulder, I wanna fucking throw my body around. I hadn’t truly been with a camera that way, which is my favorite thing to do, in so long.

ZA: We’ve worked with each other so often that we’ve developed a shorthand. I’d just be watching Mitski and Ashley on the stage and be thinking, what is the mood that is striking Mitski right now? What would Ashley like, lighting-wise, and just screaming commands to [The Egg’s] lighting crew live.

CO: Editing process for music videos is typically convoluted, and there are too many voices in the room—this was a direct line to Zia and Mitski. Mitski only had one note, that she felt like she had done something better performance-wise at the end, and I looked back through the footage and found those jumps that she does on the stage, and she was right. Her own muscle memory played into her notes process.

JF: I loved the idea of the clapping in the auditorium [that Chris added in the edit] because these haptic sounds really define a space and give you a sense of who’s watching who.

My background is primarily as a Foley artist, which I approach the same way as Ashley was describing with the camera—as if you’re in a dance with the performer, creating the sounds of movement and touch and clothing. You’re literally in the footsteps of the characters. There’s a close-up of Mitski dropping these heels, which we don’t see spurs on, but… I love the concept of the phantom spur. Even if the character’s not wearing spurs there’s something really evocative about hearing them—the immediate reference of Americana cowboy—and we wanted to set it up in the opening as Mitski shedding this old persona [from her previous album, Be the Cowboy (2018)].

ZA: The only way to make that ending work was if you, the viewer, were subjectively inside of Mitski. We shot it with “Rhythm of the Night” playing on stage as loud as you can imagine, but in the same way you can be in a club with the loudest music you could ever imagine, you’re only in your head and can hear your heartbeat, and feel sweat. It becomes the most intimate thing ever.

JF: The other major sound design element we added in that final scene, after all of the reverb build-up and the clapping falls away—I was thinking about the last time I went to a heavy metal show or performed a loud sound effect on the Foley stage and thought, What is the most subjective sound that we can’t possibly capture on set? And I was like, Oh, tinnitus.

CO: With all of these collaborators—and it's why I love working with them—there’s this really porous interplay between what is interior and what is exterior.

ZA: It was amazing watching the live chat when the video premiered and seeing all these kids being like, “Mitski invented cinematography, Mitski invented editing, give Mitski's footsteps a Grammy”—which obviously were all these other people, which is why I wanted to do this. But it’s also great because you’re seeing this audience that usually isn’t trusted with this kind of music video engage with it. I’ve been warned so many times that you have to start a music video with the song, there can’t be anything before it, because it’s “better for the algorithm” and I have to be like, “No, I’ve done a lot of these.” I know what this audience in the chat wants, and by trusting that they’re going to understand what we’re doing we’re able to get away with this. And they totally get it.

There’s this huge contingent online, Reddit threads upon Reddit threads, of people being like, “What do you think the ending means?” And, as a filmmaker, that’s the best reaction ever.

Laurel Hell will be released tomorrow, February 4. More work by Zia Anger, Ashley Connor, Monica Mirabile, Joanna Fang, and Chris Osborn can be found via their respective websites. The full credits for “Working for the Knife” are as follows:

Director: Zia Anger

Producers: Meghan Doherty and Daniel April

Movement Direction: Monica Mirabile

Director of Photography: Ashley Connor

1st AC: Karl Elchinger

2nd AC: Jill Malouf

Gaffer/Key Grip/Dolly Grip: Dan Debrey

Stylist: Tiffani Williams

Stylist Assistant: Audra Gooch

Hair and Makeup: Maria Ortega

Production Coordinator: Joe Stankus

Production Assistant: KC Crow Maddux

Editor: Chris Osborn

Sound Design: Joanna Fang

Color: Nat Jencks at Technicolor-PostWorks NY

BTS: Lucas Carpenter