Like any festival, Light Field is a test of endurance for both audience and organizers. Though here, the expected fatigue is tempered by necessary pauses built into the screening apparatus. Time swells when punctuated by intervals of darkened quiet during reel changes. Projectionists’ flashlights, wielded by Linda Scobie and John Davis, scatter shadows over the walls as they prepare to throw the next image, a cue to appreciate the artificial darkness the organizers achieved by blocking out the windows with cardboard—scraps saved from the prior year, no less. These sights and sounds at the peripheries of the screened image speak to the scrappy labor sustaining the festival behind the scenes, and an irreverence for institutional polish in favor of a more collectivist vision.

The festival is organized and run by a collective of artists including Samuel Breslin, Zachary Epcar, Trisha Low, tooth, Syd Staiti, and Patricia Ledesma Villon, in collaboration with projectionists Linda Scobie and John Davis. Now in its fifth fully realized iteration, Light Field continues to hold down an increasingly rare niche as an entirely analog small-gauge film festival, working alongside a small handful of Bay Area spaces and distributors with commitments to celluloid, like Artists’ Television Access, SF Cinematheque, and Canyon Cinema. The ease with which these names circulate through the room makes it clear that while the festival is assembled by the frenzied hands of a small team, it is buoyed by a fervid lace of local and distant supporters. Borrowed projectors, courtesy loans, and venue costs fronted against speculative ticket revenue reveal a robust lending economy built on deep trust. Though Light Field scrapes for funding year to year, it’s built a reputation for paying artists—a bewilderingly exceptional commitment in an art world bent on perpetuating precarity. Amid the festival’s often provisional logistics, this ethos proves remarkably steady, a reminder that what unfolds on-screen is inseparable from the economic and material flows that carry it into the room.

Light Field unfolded across seven programs hosted at The Lab, each devised by a different member of the collective, save for a program of expanded cinema works by Luis Macias, curated by the Light Field members collectively, in which Macias stayed, through image, sound, and smell, with the crisis of the burning frame. Programs are loosely thematic, reflecting affinities, urgencies, and contingencies threaded across festival submissions and the archival works shepherded by each programmer.

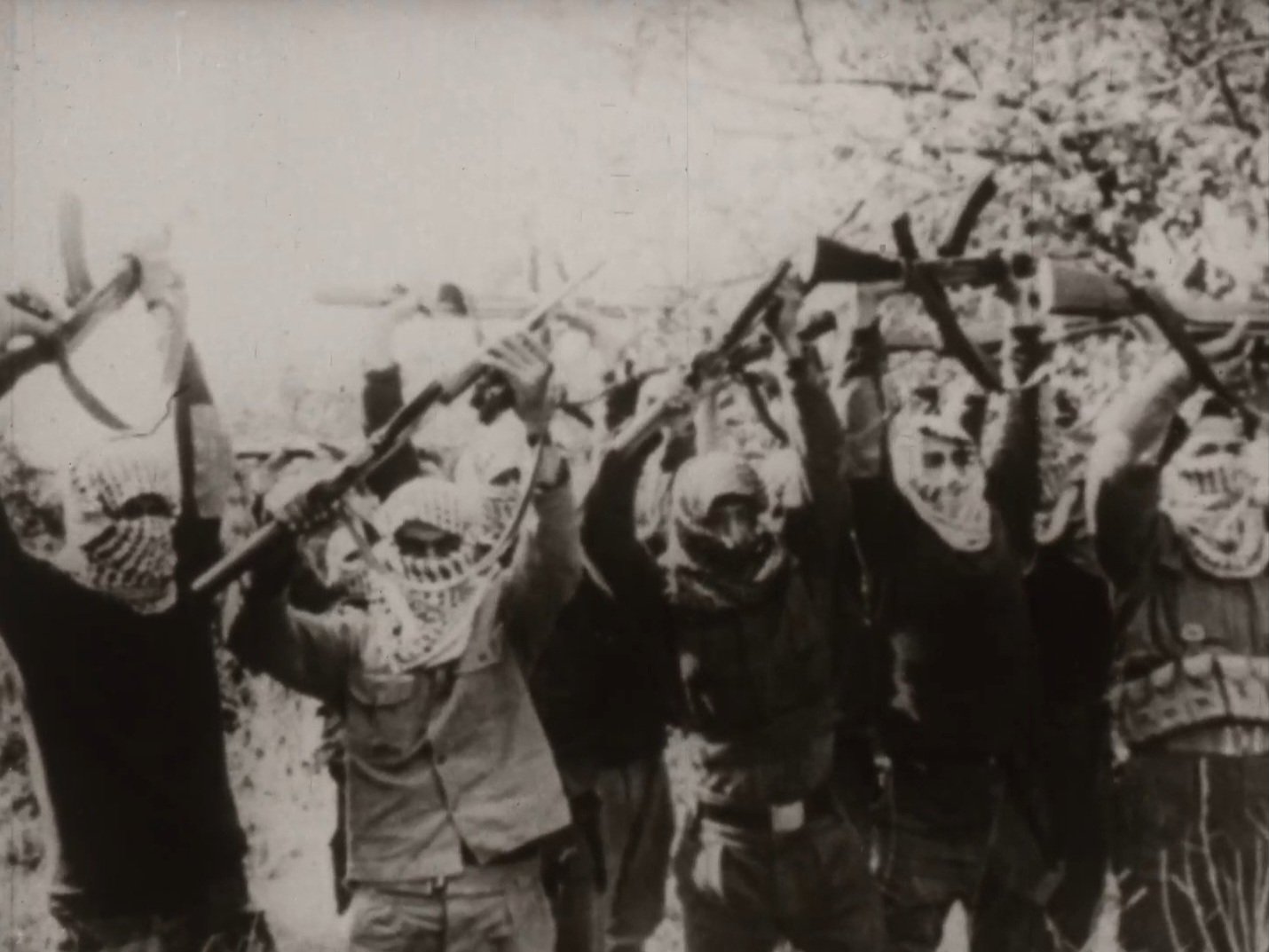

One such archival resurgence was Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan’s Palestine Vaincra (Palestine Will Win) (1969), which closed Program 4, organized by tooth. A revolutionary film composed largely of still images, it channels a Bandungian vision of Third World anti-imperialist resistance that’s both archival and immediate. According to tooth, it is among the earliest Palestinian liberation films made by a non-Palestinian filmmaker, gesturing toward an international ecology of print media documenting and conveying the liberationist movement. The showing at Light Field is thought to be the first time the film has been projected in over half a century, as it was considered lost until last Fall, when two prints were recovered independently from the Prelinger Archive and Newsreel collections. A transfer of the copy at Newsreel will also screen at Prismatic Ground later this month. Additional films in Program 4 explored relationships between film, body, land, and light—a game of tag, an illusionistic relevé, landscapes reworked by photochemical processes, forms carved from after-images. A well-suited argument for the festival’s title, light is the tool by which cinema’s imprint is produced, both materially and perceptively.

Other programs similarly took up the materiality of film: its textures, rhythms, and touches. Malic Amalya’s Plastic Aortas (2024), a hypnotizing sway with petroleum desire and a reminder of celluloid’s kinship with the microparticles that infiltrate our bloodstreams, anchored Zachary Epcar’s program, where malleable materiality marked diverse temporal registers. Films in Trisha Low’s Program 2 considered structures and shades of intimacy, looking to architectural wanderings that span personal and state imaginaries, as in Lily Jue Sheng’s haunting Heritage Architecture (2024), or the dance of light across walls, registered as light upon film in Ryan Marino’s Half Light (2023). Kioto Aoki’s 逆立ち逆立ち : If pinholes were right side up, I would be doing handstands (2024) and Ulrike Schild’s Apfelesser Guter Küsser?(Appleeater Good Kisser?) (2024) gave pause for whimsical ways of looking and drawing near with exacting concision.

Samuel Breslin’s Sunday program considered the different relationships between animation and moving image. Rennie Taylor’s single shot merry-go-round ride in Spinning (2019) relocates cinematic motion from foreground to background. Isaac Sherman’s a shifting pattern (2024) orchestrated a procession of after-images through pulsing single frames of flowers and darkness. Three films by the late animator Eli Noyes—Alphabet (1966), Sandman (1973), and Clay (1965)—closed the program with play in additive and subtractive animation methods that extended the program’s complication of image and interstice through playful imagery. Breslin’s heartfelt introduction—“we’re a community, it’s too late, we’re interlinked!”—echoed throughout, as one more effusive gesture toward presence and togetherness across moments in the dark.

The final program, curated by Patricia Ledesma Villon, explored abstraction in perhaps the most elemental way of the entire weekend. Cinema’s core formal traits—color, depth, surface, movement, shape, figuration—and structural components—lens, projector, screen, reel, audience—were each denaturalized in turn. Christopher Harris’s b/w (2023) invited the audience to voice the names of black and white paint sample names on-screen, turning color into a conduit for sound, speed, and spectatorial play. A perfect close to a weekend of cinematic devotion, Program 7 felt closest to curation as verse, or as prayer.

From Syd Staiti’s program, Zack Parrinella’s short and incandescent INCHOATRACIES (2024) nestles a demand amid chaotic tableaus: “When does academia become aphonia? When does aphonia become academia?” Shown in the first program of the weekend, the film’s provocation hangs against the festival's sparing use of didactic framing. Part of what makes Light Field so capacious, aside from its assiduous operating ethos, is its refusal of the contemporary curatorial imperative to render meaning immediate, legible, or fixed—a logic that grooms creative work for easy instrumentalization. In contrast, Light Field leaves room for encounter over prescribed interpretation.

To sit in darkness with flickering images and no roadmap is to loosen habits of consumption shaped by an insatiable desire for elucidation. Light Field creates the conditions of possibility for slowness, patience, and receptivity to the singularity of chanced materialities resisting tidy articulation. Meaning, if it comes, arrives obliquely, less a conclusion than another aperture.