It’s a good pairing: Serge Leroy, the director responsible for some of the cruelest French crime films of the ’70s, and Jean-Patrick Manchette, the most esteemed crime novelist in France after 1968. Claude Chabrol is responsible for the most famous adaptation of a Manchette novel, but his 1974 version of Nada is a bit reserved, comparable to the academic instincts of Costa-Gavras’s political thrillers. It lacks the muck that gathers on the boots of Manchette’s characters. By contrast, it’s easy to see why the director of the flashy heist film Le mataf (1973) and the violent revenge film Le traque (1975) would fare well with the themes and style of the novelist behind The Prone Gunman and Fatale. For Legitimate Violence (1982), Leroy worked from an original scenario co-written by Patrick Laurent, who had previously collaborated with Manchette on the film La guerre des police (1979).

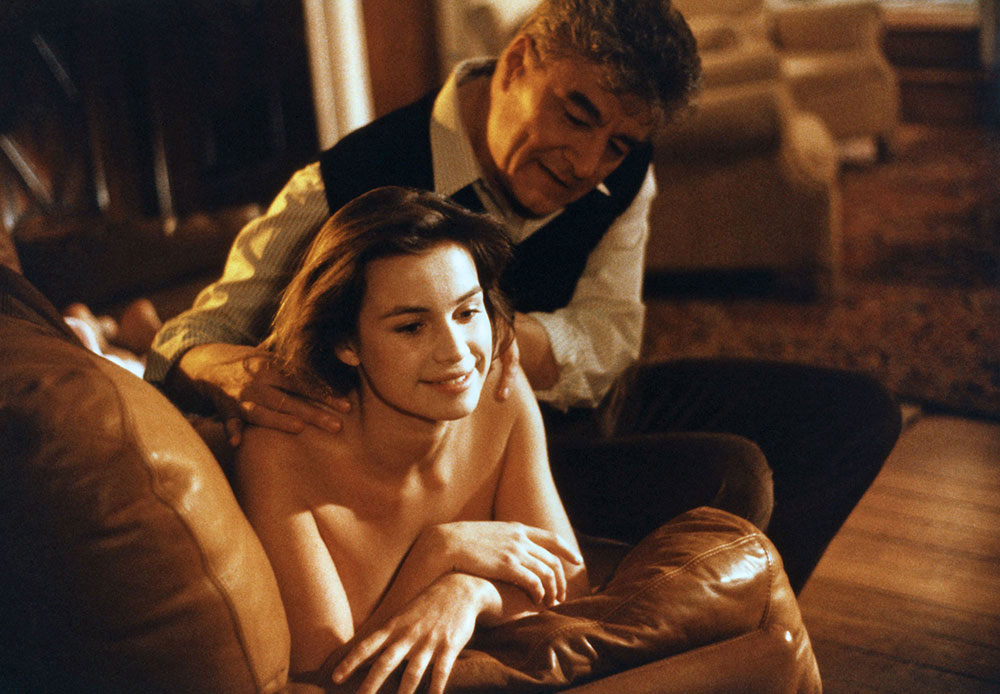

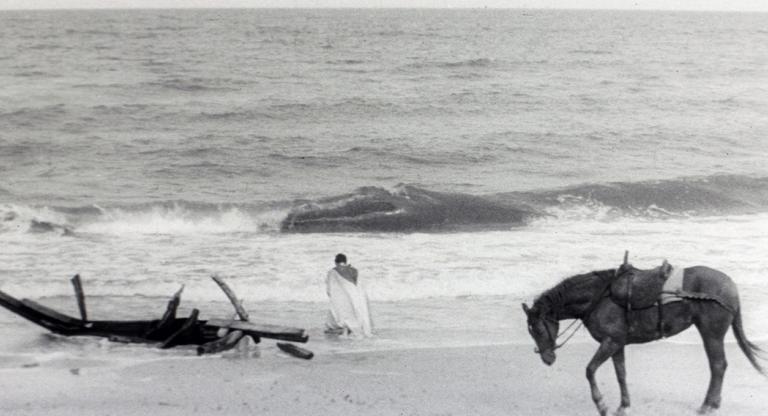

Like much of the contemporaneous Hollywood cinema (The Driller Killer, 1979; Blow Out, 1981), it is a work of despair at lost causes. Martin Modot (Claude Brasseur) witnesses the massacre of his family by an armed gang (led by a young Christopher Lambert) at a train station in Rouen in what at first appears to be a bank robbery gone wrong. He’s approached by a man representing an organization that publicly advocates for the restoration of the death penalty, but which secretly operates as a right-wing militia encouraging vigilante justice, offering to aid the hunt for the killer. Like Manchette’s debut novel, The N’Gustro Affair, the film is loosely based on current events, in particular the 1981 Auriol Massacre, in which members of a clandestine Gaullist militia assassinated a local police chief formerly associated with the group. Among the factions at play, there is no presence of a left-wing alternative; the victory of the right is a foregone conclusion.

Mike Davis once called the themes in Chandler’s novels fascist; one could say, inversely, that Manchette’s work thematizes fascism. Put differently, it follows the model left by in Godard’s Le petit soldat (1963, itself following the example of Preminger and Lang) and developed by as varied a group as Yoshida Kiju, Rogério Sganzerla, and Abel Ferrara, exploring the psychology of a society drawn to fascism. Genre conventions demand we call Manchette’s stories “political thrillers.” It is more accurate to say that they depict the breakdown of politics: kidnappings, assassinations, espionage, and terrorism are the substance of his work. Not much can be said of the director, Serge Leroy. Though he worked with a number of big names in French cinema—Michael Lonsdale (Le traque), Jean-Louis Trintignant (Les passagers, 1977), Brasseur—he never managed to attract much critical or commercial attention. The review of Legitimate Violence in Cahiers du cinéma is far from kind, but in retrospect we can say that it is likely his finest and best-executed film, the one to get closest to realizing labyrinthine cross-cutting of Manchette’s novels on the screen.

Legitimate Violence screens tonight, November 1, at BAM. It is presented in conjunction with the New York Review Books, who will publish a translation of Jean-Patrick Manchette’s Skeletons in the Closet on November 7.