“A white man!” screams a Malay villager as she stares into the camera before fleeing in terror during the opening moments of Lav Diaz’s Magellan (2025). A post-colonial epic that tries to rewire our whole schema of colonizer and colonized, the film uses the biography of Ferdinand Magellan to deliver something close to an origin story for colonialism itself. Circumnavigating the globe, yet starting and ending in Southeast Asia as an apparent counter to the age of discovery’s inherent Eurocentrism, Magellan takes an ambivalent and nearly ironic approach to its subject to pull apart familiar ideas of savagery, civilization, discovery, salvation, and heroism.

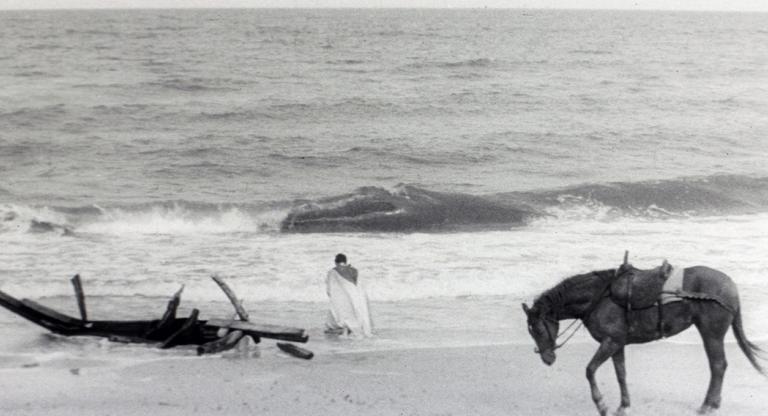

Working with an international star, Gael García Bernal, for the first time in his career, Diaz dances around our sense of Magellan as a great historical figure through distanced camerawork, elliptical storytelling, and long sequences with sparse dramatic action. García Bernal, for his part, radiates presence even while trawling through the fringes of the frame, crafting Magellan as a stolid, towering figure even while barely a speck in the frame and helping to build the dialectic between Magellan as icon and Magellan as an ordinary, fallible, and even puny man. If Magellan represents something of a historical, geographical, and budgetary expansion on Diaz’s long project of exploring cycles of historical violence in the Philippines, it does so without compromising any of the austerity and conceptual rigor familiar to fans of his films.

After catching the movie at the New York Film Festival and the Black Nights Film Festival in Tallinn, Estonia, I was lucky enough to talk with Diaz about his motivations for the film and the process of making it.

Joshua Bogatin: I thought we could start by talking about your relationship to Ferdinand Magellan.

Lav Diaz: Magellan is very much a part of our culture. Christianity and Catholicism started with him. You go to the Philippines and one of the most popular songs in our country is called “Magellan.” There've been movies about Lapu-Lapu killing Magellan and children's books about Magellan. I had an idea to change, or rewrite, the public perception of Magellan. To counter the myth in a certain way.

I want to look at him as a real person, to understand the way he would do things. You make films about big figures like Napoleon, Alexander the Great, or Jesus Christ, and they're always super human. I just want to talk to Magellan. To know what they were talking about at the time. My goal with making Magellan has always been to understand him. To know why? He’s still a mystery to me. Even after doing a lot of research, he remains a mystery man.

JB: The film, in some ways, views him as an origin point for colonialism. But, it also has a somewhat ambivalent perspective on colonialism.

In the first shot of the film an indigenous Malay woman looks to the camera, almost looking at us, and gasps, “A white man!” before fleeing in terror. The film posits us as colonizers at its opening and yet by the end of the movie it’s become a first-person narration explaining the events that happened. We move between these two perspectives in a sort of ambivalent or almost contradictory manner. Was it important for you to actively question our perspective as colonizer or colonized?

LD: There's an urgency to the opening and to showing the indigenous perspective. There's this folklore that the white man was coming to save us. Any indigenous culture has that kind of myth: that somebody would come. It’s the same with the Malays. The untouched indigenous peoples in our region, they still have the Lord, they still have that narrative that somebody will come to save them.

The very first shot gives an urgency to the story. It brings up that myth to confront the issue. The white man is not coming to save us. He will come, but the idea of colonization is to fracture us. I want to create a discourse on it, on the idea that the Messiah will come to save us. We have to destroy that long-held belief, because it destroyed us and our culture. Part of the making of the film is not to revise history, but to confront and demystify these things. It’s socratic and asks us to have a dialogue on it.

JB: You've talked about the socratic nature of your films in the past and their educational aim; however, your other films are almost all explorations of traumatic violent events in Filipino history. This is your first film in some time largely set outside of the Philippines. Do you conceive of the audience for Magellan differently, and of how it confronts or provokes that audience?

LD: I'm thinking of both Filipinos and non-Filipinos. What happened in the Philippines is very parallel to other histories. Mexico, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Korea... The discourse of colonization is universal. We have the same experiences and struggles. I was talking about it with Gael García Bernal during the early incarnation of the work, because he has a vast knowledge of it also. We’re talking about all of these incursions and the impositions of foreign perspectives in our psyches and cultures. You go to contemporary cases like Ukraine and Gaza, and it’s still the same. The cycle keeps repeating. Magellan is not old or new, it’s been there forever.

I find it funny that even in the Philippines they keep repeating in school that Ferdinand Magellan discovered the Philippines. What are they talking about? How did he discover us? Maybe we discovered him. We’ve been here forever. The discourse of discovery is really absurd.

JB: Rajah Humabon, who is a central figure in the film, is famous as the first Filipino christian.

LD: Yes, but in my version they trick Magellan.

JB: I read that there’s a little bit of historical contention over that and how you portray Magellan’s death. You claim Lapu-Lapu isn’t real and Rajah Humabon set Magellan up to die. Did you find a historical argument for that or are you speculating for its poetic value?

LD: It was based on my research and investigation, because if you do the research you have to be an investigator as well. In the case of Magellan, I was collecting things, connecting it with the accounts of the survivors and data that I found. Things don't connect. [Antonio] Pigafetta [the contemporaneous chronicler of Magellan’s expedition] always depicted Humabon as stupid, a small funny guy with a big belly. That's how he described him. But, if you read between the lines, like in the case of Lapu-Lapu, you find something else.

Magellan was able to convert the whole island of Cebu in about a week. Then he became really ambitious and messianic. He acted like a god and said, I want to stay here as your governor. He knew he couldn't go back to Spain because he marooned the son of the bishop of Spain and if he went back to Spain the bishop was going to kill him. So, when he said he wanted to stay, Humabon said okay, but there's a guy on that small island who didn't want to convert. His name is Lapu-Lapu. Magellan said, okay, I'm going to kill him because anybody who won’t convert is going to die.

When they went there, 60 Europeans encountered 2,000 Malays waiting for them. Is that a battle or just a massacre? If you're a good investigator you connect those things. There are a lot of gaps in the narratives. 50 years later, after the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, the guy who was sent to govern Mactan Island, where Magellan died, reported back to Manila that the island was uninhabitable. He found 200 people living there. So, 50 years earlier, when Magellan was killed, where did the 2,000 warriors come from? It was planned. It was a set-up.

It’s crazy when you discover these things while you're researching. You can sense that all through the narrative of Pigafetta, he was trying to clean up Magellan and turn him into a god. It's all hagiography. When Magellan died, he called him our light, our God, our Lord. And, nobody ever saw Lapu-Lapu. None of the other expeditions that came.

JB: Do you see the film as an anti-hagiography?

LD: There’s always this thing of depicting indigenous people as savages and of Magellan coming in as a heroic figure, playing the role of the white Messiah to emancipate the indigenous peoples of these islands. It's not really anti-hagiography, but anti-glorification. I don't want to judge him in any way. I want to base things on my research. I think he is a true warrior because of his training as a young man with [Francisco de] Almeida and [Afonso de] Albuquerque. He was with all the big guys all over Europe. When he decided to propose this thing to King Manuel I, King Manuel was so jealous of this guy who was like a rock star.

JB: I was curious about Magellan’s wife Beatriz. Of all the European characters, she’s the least wrapped up in these cycles of violence. She stands out in her innocence and devotion. I read that originally the film was focused on her and that there might even be a parallel film, an eight-hour-long companion piece to Magellan mainly about her. Does that exist and what was your interest in her story?

LD: The early incarnation of the material was called Beatriz, the Wife. In my research, I found out that there's nothing about Beatriz. So, if you're doing this epic, the easiest narrative would be Beatriz because you can invent her. She’s just mentioned in one line as the wife. She was 19, but other than that there’s very little information. You know how women were depicted then: if you’re not a queen, you’re zero, you’re invisible. So, Beatriz was nothing. When they asked me to do a first draft for funding, I called it Beatriz, the Wife. It’s almost like a Phantom of the Opera thing where I just invented the character Beatriz. It was even a musical then, with the phantom of the death of Magellan haunting her until he died. But during the course of the research, I went back to Magellan because I had to go back to my original goal of representing the Malay in the film.

JB: You put a lot of emphasis on the environment in the visual language of the film—the landscapes are often given more prominence in the frame than the drama of the narrative, which is usually observed from some distance. Why is it important for you to treat your narratives with this sense of distance and to show them having an almost miniscule relationship to the natural world around them?

LD: My work has always been that way. The static shot is my language. I always go with a very journalistic way of seeing things where I'm just observing. I don't want to impose things. I don’t want to have the coverage of movie-making we often see. It's been overused. It's still valid, but I just want to be the observer. For people who got used to the way we look at cinema, it's boring. It's slow. It's as if nothing is happening for them. But if you look deeper, so many things are happening. Nature is a big, if not the dominant, protagonist of the canvas. The weather, the wind, the water, are all big actors in the frame. Everything is a part of the canvas, not just the action of the protagonist. It's a very disciplined way of doing things and it's hard. That's why I'm doing the cinematography myself. A lot of cinematographers ask if we can do the close-up, the cutaway, or the medium shot. Come on. It’s my language, my way of articulating the image, the visual language of cinema. But, I’m also not very dogmatic about my methodology. I also want to do a genre film soon.

JB: You've done genre films before, musicals and sci-fi movies.

LD: Yeah, but I can go deeper as well. I can do horror. I can be very gory if I want to. At the same time, it's hard to articulate what visual language is. What’s cinema? What’s an image? For me, the discourse of the image has to have a relationship to how I think and where I come from.

I’m Malay and my culture has always been so attached and dependent on the ways of nature. Nature is such a big actor in our lives. We are the most typhoon-damaged country in the world. We have 20 to 26 typhoons in a year. It's too much, but we’re so used to that. The way we live with nature has become ideological in a way. We can't escape it. It's like a moral line as well.

In my cinema, I’m always thinking of how I can use nature as a big actor. It’s at the bottom of my culture. I don't want to call it an ideology in cinema, but it’s maybe part of my methodology. Part of my discipline is to impose my culture as well, the way I see things. I’m detaching and reattaching in a way. It’s not a dogma. I can go back to doing horror or action. I can go back to my early days and the full coverage cinema. I love that as well.

JB: Talking about gore, why did you choose not to show any of the fighting, but only the aftermath of the battles? If you wanted to make a gory movie, that seems like a good spot for epic bloody action.

LD: It’s been that way in my movies. You can see in Norte [2013] that I avoided showing violence as a spectacle. Movies often make gore, blood, and killing fun. They even do slow-motion of bullets and stabbings. For me, it’s obscene to do that. You can do gore in a different way. I’m talking about gore and horror. It can be a horror film, but I still want to do it my way. I still want to respect the human thing.

When I was a young journalist working as a beat reporter, I would go to the crime scene and the dead body would already be there. You didn’t see the violence, but you knew that this was the consequence of that violence. The film is articulating it in a very different way. There’s more respect to the human condition than if you have all of this spectacle glorifying violence and barbarism. For me, that’s obscene.

Magellan screens January 9-15 at IFC Center. Director Lav Diaz and star Gael García Bernal will be in attendance for select screenings.