On May 6th, the pride of the Bronx, high-concept/low-budget auteur Larry Cohen, returns to NYC with a two-day binge of his New York-set films screening at the Quad Cinema. Alongside perennial favorites Q (1982), Black Caesar (1973) and The Stuff (1985), the Quad offers more obscure Cohen fare such as gonzo conspiracy thriller The Ambulance (1990) and Hollywood takedown Special Effects (1984). These films have a symbiotic relationship with the city every bit the equal of canonized Gotham films like Taxi Driver and Do the Right Thing. Cohen himself will be present for six of the series' seven screenings.

The Cohen signature starts with tabloid simplicity: a dragon terrorizes New York from atop the Chrysler building! Mass shooters claim divine mandate! Ambulance abducts diabetics for nefarious experiments! Mutant killer babies stalk the suburbs! His screenplays deepen such conceits with broad satire (he’s tackled race, consumerism and the nuclear family) and subtly drawn characters (alcoholic lounge acts, anxious fathers-to-be, lapsed Catholic cops.) His work revels in the grime and splendor of public spaces. In the New York films—he’s also a master of suburban paranoia, but that’s another series entirely—the authentic rhythms of urban life bleed onto the screen. Audiences simultaneously feel the pressure exerted by the metropolis upon Cohen’s shoestring productions and the director’s heroic counterpunches in pursuit of a wholly original vision.

The highlight of the weekend is the New York premiere of the exceedingly rare "Whisper" cut of Cohen’s 1976 magnum opus, God Told Me To. A genre- and mind-bending consideration of higher powers and mass killings, God Told Me To earns a position alongside the true masterpieces of American independent cinema. The “Whisper” cut — named for the film’s original title — features a temp soundtrack of borrowed music by Bernard Herrmann, who was set to compose a true score before tragically dying less than 24 hours after seeing this rough cut of the film. The "Whisper" cut also boasts a half dozen scenes not found in the theatrical release as well as fewer special effects shots. Screen Slate spoke with Cohen via telephone about the two cuts of his greatest film, as well as his production methods and views on modern Hollywood spectacle.

Your films always have a wonderful sense of place. Do you have locations in mind when you’re writing?

Sometimes. But everything is subject to variables like if any kind of a celebration is going on, like the San Gennaro festival in Little Italy. I’ll try to write that into the story. For an event like the St. Patrick’s Day parade, I try to invent some reason for that to be in the movie. It depends on the time of year I’m shooting and what’s going on.

Especially in your New York-set films, it almost feels like city is happening to the actors and the film itself, rather than the feel of a larger budget film where you get the sense that the filmmakers are in control of the city. Have you ever wanted to exert more control over your locations, shutting down several blocks or using hundreds of extras?

Well, I’ve done a lot of stuff that looked like we shut down the city. Carrying machine guns on the Chrysler building, and having a gunfight in the middle of the St. Patrick’s Day parade, and all of the chases we did. We had an actor being shot down in front of what is now Trump Tower. We wouldn’t be able to do that anymore. Most of the stuff we did we wouldn’t be able to do anymore. There’s so much security and people get so paranoid about everything. It’s just not a good idea anymore to run around the streets of New York with a gun in your hand. But we did it in those days. We drove a taxicab up on the sidewalk and drove for a few blocks and nobody stopped us.

I just loved the fact that I kind of owned New York. I very seldom go around the city that I don’t pass a location that we shot. I just love this city, it’s the world’s greatest backlot.

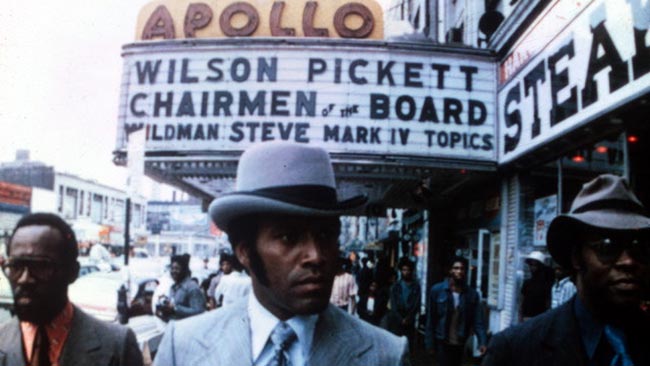

Fred Williamson in Black Caesar, 1973

Were there ever times when you were writing and had to throw something out, thinking “there’s no way I’ll be able to afford that”? Do you have budget in mind when you’re writing?

To tell you the truth, I don’t.

Really?

I have no budget in mind when I’m shooting, either. I never know how much we’re spending. I just know what the budget of the picture will be at the final accounting. And I always come in under budget. Always, without even looking, because we operate with a very small group of people. We don’t have a big production office with a lot of people sitting around. We just have the crew that shoots the film: the camera crew, the sound crew. We keep it to a minimum and I like to move around quickly and with as few people as possible.

I don’t want too many people asking questions, or people sitting around doing nothing. A whole bunch of young people with walkie-talkies, trying to make themselves important. I tell everybody at the beginning, "Any questions you have, don’t ask anybody else, come to me directly. Even if it’s something inconsequential like your trailer or your meals or picking up your mother at the airport. Let me make the decision to do it. Don’t go asking crew members. I don’t want anybody making any decisions about anything except me."

And at the end of the day, after everything has been shot and the cameras are being wrapped up, I have to go in the corner and sit with a checkbook and write all the checks. I take care of all of that myself.

You’ve removed most of the excess from the process.

Oh yeah. There’s usually a whole staff of people and a whole group of people that have nothing to do with the picture wandering around, saying things they shouldn’t be saying and offending people they shouldn’t be offending, trying to be important. That’s the trouble: the more people you get, the more self-important they get. I want it understood: nobody has any authority but me. That’s it. The actors love it because they’ve never worked with anybody who has total control before. There’s always producers, associate producers. I mean, just look at some of these shows you see on television. You see how many producing credits there are. There’s sometimes six, eight producers on a picture. Whoever heard of such nonsense? I don’t have producers on the picture. I’m the producer and the director and the writer and the editor and the special effects supervisor and everything else. I don’t want anybody else to get a job.

I was going to ask you if you were ever envious of filmmakers who are able to spend as much as they want, but it sounds like that proposition is unattractive to you.

Well, they can spend as much as they want because when they get [to set] they have to rethink everything that they’ve planned and it ends up costing twice as much as they planned. Some people have unlimited budgets, but for some reason I don’t envy them. I know that making a big production with a lot of money requires a lot of supervision from other people, a lot of people looking over your shoulder, looking at your dailies, making judgments of how you’re doing, giving you warnings that you’re going over-budget. If you go over budget enough and you don’t have a success you end up never working again. Even people who win an academy award: they make a picture that goes over-budget like Heaven’s Gate, and that’s the end of their career. You know, that’s demonstrated in Special Effects, which is playing at the Quad cinema, with Eric Bogosian playing a washed-up movie director who went over budget too many times.

I never make pictures unless I’ve already sold them before I start shooting. And so I know how much they’re going to give me for the picture and if I come out under budget I get to keep all the money. I always end up coming in under budget, but I never look from day-to-day or at the end of the week to see how much we’ve spent, I just make the picture, that’s it. I don’t look back.

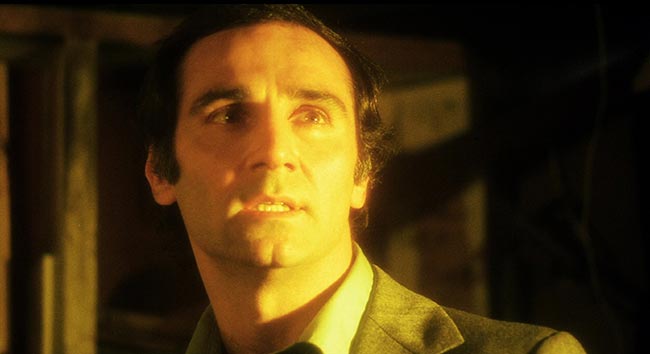

Eric Bogosian in Special Effects, 1984

Do you revisit the films after they’re completed?

Oh, I hear all these directors say they can’t look at their movies after they make them, but that’s not my way of doing it. I get too much of a kick seeing a picture in a theater with an audience.

Your commentary tracks for DVD releases are among the most edifying and entertaining, and in them your love of classic Hollywood is clear. Are there any filmmakers working today who you follow or look forward to seeing work from?

I enjoy most of the original kind of guys. I like some of Woody Allen’s more recent pictures. Some of them I didn’t like, but at least he keeps making movies and he loves to make movies and that’s his life. I look forward to his pictures, even though some aren’t as good as others. They can’t all be literature, though.

I’m not a fan of the big budget special effects movies. It seems to me that too much of the picture gets bottomed out. The director of the picture doesn’t really direct the whole film. They turn it over to a special effects house and model makers. All you have to do is sit there at the end of the movie and watch the final credits, which usually takes 10 minutes, and all these names come up and you realize there will never be unemployment as long as they make these movies, because there must be a thousand people who worked on the picture. God, I could never stand working with a thousand people on a picture. With my credits, you’d be lucky if you had 25 people.

I just don’t want all those people around. And you have to feed them. They don’t do anything, so they’re not necessary to be there. You have to feed them every day and you have to provide them with transportation and with parking. In New York City, [parking] is a very expensive proposition. I don’t want all those people around unless they are going to provide a real function on the picture. Now, a lot of movies are made with union crews, and the union requires them to take a certain number of people. So whether you need ‘em or not, you gotta take ‘em. I think that’s an absurd way to do creative work.

God Told Me To, Q and the It’s Alive trilogy all have sizable audiences, but is there one of your films that you wish had a larger audience or one that you’d like people to revisit?

Perfect Strangers (1984) was one of the most challenging pictures I’ve made, because the star was a two-year-old boy who doesn’t talk. He hasn’t learned how to talk yet. And yet, I had to direct him in a very large role in very complex scenes. He had to do a lot of things that you couldn’t imagine a child could do, even if he was five-years-old, much less two. So I think that was a real experiment and I enjoyed doing it, particularly because I was able to get the kid to do what I wanted to do.

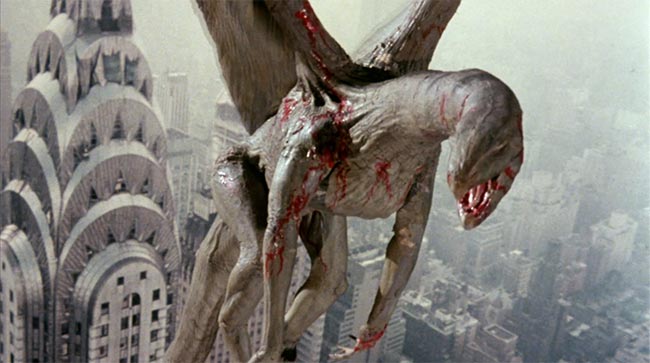

Q: The Winged Serpent, 1982

Countless filmmakers have lamented how hard it is to work with children who are even older.

Yeah, he was two-years-old! Today the guy is probably 35 and is living up in Canada somewhere. At any rate, [Perfect Strangers] is a thriller full of suspense, with a lot of good twists. It has some very Hitchcockian action sequences, which I devised and shot all by myself, without a need to bring in a team of writers. I mean, you see pictures today and four or five people get writing credit on a picture. Not to mention the three or four who don’t get writing credit. A lot of pictures have eight writers, nine writers. God, I never heard such nonsense in my life. I’m telling ya, it goes on and on. And they think if you have more writers the picture’s going to get better, but the truth of the matter is it gets worse. So I’ve never had that problem. I don’t collaborate. They say moviemaking is a collaborative effort, but not me.

That reminds me of Francis Ford Coppola declaring in Hearts of Darkness that film directing is "the last dictatorial profession."

Yeah, but Francis has had a good-size crew. Look at Apocalypse Now, they shot for months and months and months and half the crew probably died while making the picture over there in the jungle. The only real collaborations I’ve had are with the composers of the movies. I had Bernard Herrmann, who was one of the greatest composers in the world and he became a very good friend. I also had Miklós Rózsa, who did every imaginable great movie: Double Indemnity, The Lost Weekend, Spellbound for Hitchcock… these were people whose music I had admired ever since I was a kid. I got to work with them and I certainly didn’t tell them how to write their music scores. I did hang out with them and befriend them and all those relationships ended up being lifelong friendships.

Tony Lo Bianco in God Told Me To

What’s the history of the "Whisper" cut of God Told Me To?

It was a pre-cut of the movie. It wasn’t meant for distribution, it wasn’t meant for exhibition. It was simply a compilation of the scenes of the picture, many of which are not in the released picture. So people who see it will see five or six or seven scenes that were not in the final film. I think this rough cut is actually better than the finished picture. It doesn’t have a few special effects scenes in it, but I think the picture’s better without the special effects scenes. I’m sorry I put them in in the first place!

[The "Whisper" cut] doesn’t have the final score that was written by somebody else. Bernard Herrmann had died, but it has excerpts of Bernard Hermann’s music. And Bernard Herrmann saw the movie, as a matter of fact, the night before he died. It was the last movie he ever saw. He had finished scoring Taxi Driver that day and came over to the studio and I showed him God Told Me To. We made some notes, had dinner, he went back to his hotel and he died that night. It was tragic. The picture’s dedicated to him.

Any chance the "Whisper" cut is going to see a wider release on DVD or in theaters?

It can’t be shown in regular distribution. It can only be shown in kind of an arthouse exhibition, one showing or something, because the music is not licensed to be on this movie. It was tracked on in order to just show it to people before we finished it in terms of getting distribution and all that kind of stuff that you need to do. Even though I had already sold the picture, the people I sold it to wanted to be able to show it to other people in order to get distribution. So I had to have some kind of a cut and that’s what we have here. I think it’s a better cut than the final one.