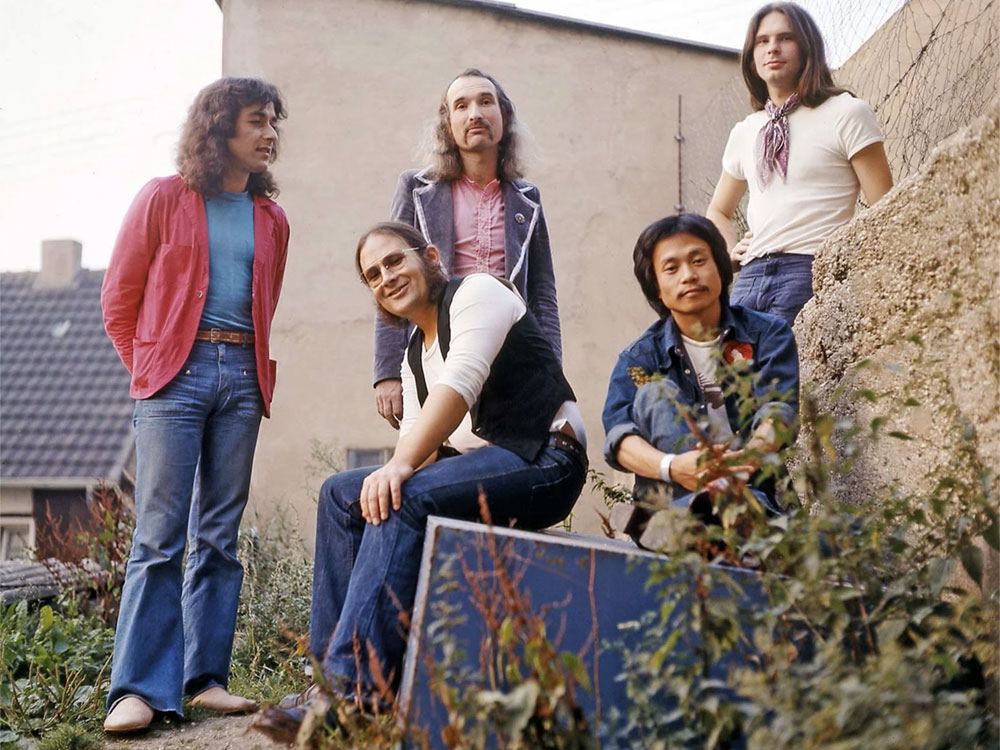

Tuesday, June 7, the first Screen Slate Presents begins at Spectacle with an evening spotlighting the soundtrack work of German rock legends CAN. Though best known for their full-length LPs, CAN was a go-to film score source for Germany's brightest filmmaking talents in the late '60s and early '70s. This aspect of the band's career waned as their recording and touring took off, but CAN managed to score a total of sixteen films for directors including Wim Wenders, Jerzy Skolimowski, and Samuel Fuller. Though the band's music has rarely gone out of print and continues to influence artists including Sonic Youth, Pere Ubu, This Heat, Chrome, The Fall, Radiohead, and even Kanye West, the films they scored have remained elusive in North America, where none are available on DVD.

June 7, I'll be showing two films represented on CAN's 1970 Soundtracks compilation album: Thomas Schamoni's A Big Grey-Blue Bird (Ein großer graublauer Vogel) and Roland Klick's Deadlock.

Because so little has been written about the films in English, CAN's founding member Irmin Schmidt generously agreed to an interview to shed some light on the films and CAN's involvement. Schmidt acted as a liaison between filmmakers and the group, assuming primary responsibility for their scoring efforts while working closely on sound design with prolific German film editor Peter Przygodda for many of the projects. He has subsequently scored over 100 films and television shows while focusing primarily on projects based on his foundation in classical composition, including Opera, ballet and sound installations. Anthologies of his film music are available on his website, and later this year Spoon Records will release a three-disc anthology of CAN's "Lost Tapes," including a wealth of material from other scoring sessions.

June 2 between early morning New York City and Roussillon, France, Schmidt and I spoke about recording in castles and decommissioned movie theaters; the cohesiveness that "She Brings the Rain" lends to Thomas Schamoni's psychic and cinematic cacophony; and how Deadlock was scored and mixed in five days before clinical collapse.

Irmin Schmidt: So how is your project going?

Jon Dieringer: It’s going well, thank you. A movie theater in Brooklyn asked me to show some films. I had recently seen Deep End and became curious about the other films represented on the Soundtracks album. The music is readily available here, but none of the films.

And you want show Ein großer graublauer Vogel, the Schamoni film?

And Deadlock, back-to-back.

Ah yeah, I see. Ein großer graublauer Vogel is a very interesting one. It’s the craziest of them all.

Frankly, it’s kind of difficult to follow. It’s really very beautiful, and I enjoyed it. But it seems like it requires a few viewings to sort out.

There are some interesting sounds in it. In the film there are these people spying on each other, and they have these electronic instruments and screens they’re working with. And for the sound in the film I recorded lots of shortwave sounds and turned them into sound design. I brought these sounds I had edited to the studio, and Can played to them. Then I edited them back into the film, and these sounds became music, and then they became reality again, and that was very interesting as sound design work.

For the music, was there an active collaboration with Schamoni? Or did he trust you to do your thing?

It was actually much more a collaboration with Peter Przygodda. Peter is the editor of nearly all Wim Wenders’ films, and one of the most famous film editors in Germany. And Grey-Blue Bird was actually one of his first major works as an editor. I worked much more closely with him on the sound than Thomas, although we all three worked very nicely together.

It seems like in some ways it might have been a significant film in German cinema, although it’s not really known in North America. My understanding is Schamoni’s experiences led to his organizing of the Filmverlag der Autoren, which produced and distributed the work of Fassbinder, Herzog , Wenders and many others.

Yes, he was very much involved in that, although this film was not such a big success because it’s much too crazy, and even understanding German, you can’t follow the story. It’s quite confusing. But it is in a way a very nice and hippie-esque version of Germany at that time. It’s not that dark, like most of Fassbinder’s work. It’s pretty strange and crazy.

A BIG GREY-BLUE BIRD (Thomas Schamoni, 1971) Trailer from Jon Dieringer on Vimeo.

Do you know what Schamoni’s intentions were? I’m curious because it’s a very exuberant work, as if he wanted to put everything he felt about cinema, about Germany, about culture into one film, and it just sort of goes all over the place.

Yes, probably. I mean, on my side of the film we tried—and I think we didn’t totally succeed—to make the story clearer. I don’t know what his intentions actually were. They were political, about art, about living together communally. You’re right, it was maybe too much at the same time. [Laughs.]

It’s interesting you say you were trying to make it more coherent, because the most consistent thing throughout the film is the recurring use of “She Brings the Rain.” Could talk about how it functions in the film? Was it written specifically for A Big Grey-Blue Bird?

No, when I started to work on the film, this song already existed without having been released on record or published. And I thought it was perfect for the film, so we used it.

How so?

It’s difficult to say, because it’s more feeling than a calculation. The song itself is sort of simple. It’s a very romantic song, and I think the film is actually very romantic. It’s in the German 19th century Romantic tradition, and I thought this song sort of gives it a kind of kind of feeling and sentiment, a fundamental feeling which goes through the film so not everything is totally strange and, well... How would you say, “impenetrable”?

Oh, for sure. I feel the best way to enjoy the movie is to sort of let it wash over you.

Exactly! Lean back and let it be.

Could you tell me a little bit about the writing of “She Brings the Rain”? It’s evidently one of Can’s most beloved songs in terms of being featured in several subsequent films, yet its also atypical as a more traditional love song.

In the work of Can, there are all aspects: traditional, avant-garde and New Music effects like Stockhausen. And the classical tradition, with which I grew up and studied at first as a conductor. I was very into the music of the 19th century like Wagner, Brahms, Tchaikovsky. My aim in founding Can was to bring together all these traditions, not only the rock tradition which came from America, but also the European traditions of the New Music that appeared in the ‘50s, or already in the ‘20s and earlier, and also the whole 19th century. And when it started I was very much into serial music and aesthetic rigidity. But I wanted to include everything which grew out of the blues, and the African music that in the south of the United States that became jazz and rock. And there is a third, very important element, which is that in the 20th century European and Western culture started to open to extra-European culture, like the Expressionists in Germany, who were highly influenced by African sculpture and art. And all of a sudden European musicians understood Bali or Asian or African music. Before, they didn’t even consider this as music. This was a very new phenomenon, and I also wanted to deal with that. So these are the elements of Can’s music, and sometimes one of these elements is dominant, like in “She Brings the Rain.” It’s basically a very conventional and simple song structure. It was created very spontaneously, and only from Michael, Malcolm and Holger. Neither Jaki nor me were there when they played it. Actually, Jacki said his contribution was just to keep silent, which is a musical decision, too—not to do something. And my contribution was sort of as a producer, because I convinced Michael to play this wonderful, distorted guitar at the end, which in the first version didn’t exist. So that was how this song was done; but nevertheless, in Can, if you play only little or play a lot or maybe only your melody is used, with everything we created, the author was the whole group. So “She Brings the Rain” is a nice case, because from five, only three played, and nevertheless all the others are known as the authors.

I’m interested in this idea of the communal authorship and the economics of the band. Although the music itself is not really at all overtly political, was there a political consciousness in the way the band was managed and functioned as a group?

Well the group was managed by Hildegard, my wife, from 1969 on, who gave up her job to manage Can. And so she was part of the group. And that was the system: everything was shared, and we were a kind of community. Of course that is political. But it’s sort of starting with politics in your social environment, and not just trying to save the world.

I’m also under the impression you were rehearsing and recording in a cinema at the time.

We started first with a very small room in a kind of castle, which was given to us for free by an art collector who I knew very well before Can, because I was very much involved in the art scene and knew these gallerists. So when Can was born, I was telling everybody, we need a room, and he came up and said, I have this sort of mansion, or castle, and there are still rooms nobody uses, so you can install yourself in there. We only worked two years in there, and later we rented an old cinema in a village near Cologne in which we installed ourselves and had our studio.

Which years were you there?

We changed in ‘72, I think, or winter ‘71. We had to do a lot of building in the cinema. We nailed 1,500 mattresses for insulation against the wall and all this technical stuff.

When you chose the space, was it more a matter of opportunity, or was there a specific appeal to you to working in a cinema?

The first reason was actually that we had to move out of the castle. There was a whole family living in it, the family of the artist Ulrich Rückriem, who were upstairs. We were downstairs with the studio, and they couldn’t sleep because we made too much noise. So after some time he wanted us to move out, and we were looking for another studio. Since at that time we could at least afford to rent one, we were looking around and found this cinema, which was empty and was cheap because the door was difficult to reach with a truck. There was no interest from enterprises which needed big space, because normally they need an entrance or something where they can get in with a truck, which was impossible. Very banal.

There’s a temptation to dig for a parallel there; your first album is called Monster Movie, you’re soundtracking films...

Monster Movie was done in the castle along Tago Mago. Then half of Soundtracks—half in the castle, half in the cinema. From then on, everything was done in the cinema.

I’m curious about the score for Deadlock as well. Was this some of your first work with Damo Suzuki?

It was one of the early works with him, but I think it was later than Deep End and “Mother Sky.” It was in the same time period. The funny story about Deadlock is that Roland Klick actually thought he could make the music himself. He played a little bit of guitar, so he was convinced that he should do it. Then the film was done, and he put his music to it, the editor, who was also Peter Przygodda, said, ‘Look, you are fucking up the film with your shitty music.’ And then the producer came and said, ‘Well, it’s wonderful, except the music.’ So everyone convinced him that he should get a proper score.

Hear Klick's music in this trailer for Supermarkt (Roland Klick, 1974).

He came and asked us about three days before the mixing of the film was done. He was sitting all night in the studio and told us how the music should go. Then finally I got furious and said, ‘Look, if you know it better, take your fucking own music, and if you want ours, you just shut up and let us be.’ [Laughs.] So I chased him out of the studio, and we started to work. After three days the mixing started, but of course the music wasn’t yet finished. So we did the music at night, and early in the morning each day I flew to Berlin. We mixed one roll with the music, and then I flew back and at night we produced the next, and so on for about four or five days without any sleep except the hour back and forth in the plane with a lot of mother’s little helpers to keep me awake. The fifth day there was some kind of discussion about something, I don’t even remember what it was, and then all of a sudden I found myself with a nurse beside me on a bed, and I had fainted in the middle of the discussion. They told me I started to cry and fell from my chair. [Laughs.] So that was a very pathetic, dramatic way of making my point. But finally I did, it was mixed like I wanted. And that was Deadlock.

Amazing. It’s a really entertaining film. Like Schamoni’s, it just sort of flies by, but of course has a much more straightforward plot. Three guys and suitcase of money.

Right, it’s not this kind of crazy hippie story like Thomas’ film. It’s very similar to the Leone spaghetti westerns.

But more contemporary, definitely that sort of cinematic language, though.

A very wonderful language, and great actors. It had great success in Germany. The television shows it nearly every two years, again and again. Quite a successful film.

DEADLOCK (Roland Klick, 1970) Trailer from Jon Dieringer on Vimeo.

And one of your favorite scores?

Oh yeah, I think it’s really good film music. It structures the film very nicely. I really like the showdown at the end with the jukebox. The idea to put it there was mine, and I think it was one of my best. When we made film music, Can never saw the film. I talked to the director and discussed the idea of what it should be. Then I’d go to the studio, tell the story, and then we created music the same way we did with the records. And my part was basically to see that it fit to what I imagined for the picture. And with this one, I think it worked really nicely.

Do you have other scores, either as Can or under your own name, that stand out as favorites?

Well, Deadlock is definitely one of my favorites in Can. Deep End, too. Skolimowski had heard the Monster Movie record, and he was totally amazed by “Yoo Do Right,” how it sort of goes through different moods and everything. So he came up and said, ‘I would love if you would make a piece of music that would go 20 minutes long through very different scenes, but is always the same yet sort of changes with the different scenes.’ So we did this piece in which every change in the film led to a sudden change in the musical structure, sound, melody and instrumentation. That was very interesting and lovely work. Skolimowski was quite happy with it, and so am I still. For my own, there is a long television series which I made in the early ‘80s, after Can, which is called Rote Erde, or Red Earth, which is 14 films about the history of the German coal miners from 19th century until after the World War. And the music to it I think is one of my favorite of my own films. And then there is a new work I did for Wim Wenders, Palermo Shooting, which I also like very much.

Do you have plans to collaborate with Wim Wenders in the future? The first was Alice in the Cities, right?

That was equally in rush, because he had no music on the film, and wanted to start mixing the next day. Peter Przygodda was again the editor. They found out, shiiit, we need music, and [Wenders] rushed to Cologne and said, ‘Listen, I can’t even show you the film. I’ll tell you the story. But I need some music, and I need to leave with it tomorrow morning because the studio is booked and I have to mix it.’ Basically it was Michael and me, and I played most of my sounds inside the grand piano with Michael and Jacki doing some sounds to it. And Wim said yes, this will fit, and no, this won’t, and that was very collaborative in a productive way. And he happily left at about 5 am for Munich and started to mix. It was not a big score, but it helped the film the way he wanted it. And ever since, from time to time, like in Until the End of the World and Lisbon Story there is Can music. And now Palermo Shooting.

Did the film scoring work help Can as a rock band?

The first album we did without having any film music, and then the film business helped us financially to survive, because in the very beginning we were totally unknown and we were not even very much accepted by a lot of people because it sounded so new, so different. From what people knew as pop music and rock music people were used basically to the English rock music in the late 60s. So people thought we could not really play because we didn’t sound like the English rock music. And that was THE rock music in Germany at the time. So it was some time until we were recognized. We were of course recognized immediately in certain circles like art and filmmakers and musicians. So of course they came, and it was very helpful for us to make film music because we needed money to survive. But at the same time it was fun to do, and it was interesting. We considered film music as much a part of Can as the other music in its own right. We created quite a lot of film music in the first year. Then after we were known all of Europe, we were touring and making records and didn’t make film music anymore.

Did you miss it?

No, not at all, no. If there’s an opportunity, I like to do it from time to time. And there are always periods where I do a lot, and periods where I don’t do any film music. From 2002 to last year, I did 26 film scores, which is quite a lot. But in the 1990s, I did only three, I think, because I wrote an opera and made other things. In the last years, I did a lot of other things, too: I wrote a ballet for the Deutschen Oper am Rhein and I made these two records with Kumo and made a big sound installation. I wouldn’t be happy being labeled only as a film composer: this is not what I am. It’s part of my work, and I only like to make music to films where the music can then stand on its own.

Special thanks to Hildegard Schmidt and Holger Czukay for arranging the interview, Professor Randall Halle PhD for the helpful background on Thomas Schamoni and Ein großer graublauer Vogel, and Spectacle Theater for hosting the film night.