“Man is a mirror in which one can discover the reduced and condensed image of the sky, a living universe carrying within him in his body and in his psyche, fires and dark shores, zones of shadow and of light,” wrote Jacques Lacarriere in The Gnostics, his seminal 1973 work on the history of the philosophical, quasi-religious movement that emerged in the 1st century A.D. Gnosticism is based on the idea that the material world is flawed and evil, and salvation is possible by a direct revelation of the divine (the Monad or supreme god) attained through esoteric knowledge. Formed during the early years of Christianity, before being denounced as heretical, it is in essence a belief based in the rejection of religious orthodoxy and the illusions offered up by the everyday world: a spiritual rebellion against what obfuscates the true nature of the universe, and an ongoing conflict between light and dark forces.

The painter and filmmaker Jordan Belson embraced this gnostic view in his visionary works on canvas and in 16mm, using abstraction to make direct contact with his viewers in pure cinematic terms. “I’m trying to make pictures that focus you and teach you about a knowledge that is beyond words, or would be tedious to try to teach in words,” he told Raymond Foye in a series of interviews for The Brooklyn Rail in the early ‘00s. “My films are always arbitrary mindstuff: nothing domestic…. The tangibles and intangibles are mixed in the metaphysic. The image as a container of wisdom and knowledge.”

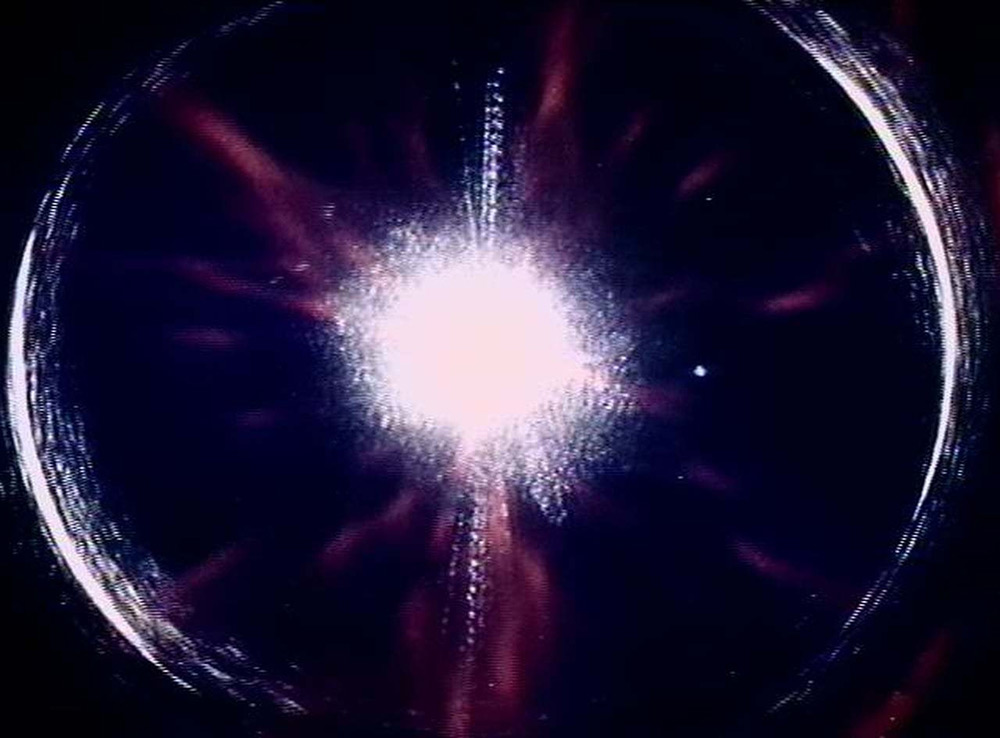

Belson’s Music of the Spheres (1977) is a mix of such tangibles and intangibles: images of planets and stars floating in space coalesce with abstract streaks of color and gleaming bursts of light, much like the evocative imagery laid out by Lacarriere to describe the gnostics. Key to Belson’s film is unceasing transformation. Nothing is fixed or static. The film creates a trance-like experience, enhanced by its ethereal musical accompaniment. Belson’s attempt to represent not an image of the universe, but an unmediated view of its nature and movement, characterizes many of his films, like Infinity (1980) and Bardo (2001).

Cycles (1974), Belson’s collaboration with Stephen Beck, is a more structural work. Created with Beck’s Direct Video Synthesizer, the film is made up of 12 iterations of the same footage that are uniquely modified by the artists on each pass. Collaboration was an essential aspect of Belson’s filmic output, beginning with Vortex: Experiments in Sound and Light, the successful series of son et lumière shows that he created alongside electronic music innovator Henry Jacobs. For these shows, which ran at the Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco from 1957-59, Belson manned up to 30 projection devices, casting lighting effects and cosmic and abstract imagery into the science center’s impressive dome.

In that spirit, Spectacle will host “Gnostic Cinema: Jordan Belson and Beyond,” a program presented by the artist Bradley Eros. The program includes new 16mm prints made from Belson’s original internegatives and films like Jeanne Liotta’s Observando El Cielo (2007), an expansive look at the cosmos seen from an earthbound human perspective that was captured over the span of seven years on 16mm. Eros will also meld Belson’s works with his own (Mediamystics and Vampÿrates), using celluliod and multi-screen projection to create a unique, spontaneous, and ephemeral collaboration. The performance is designed to capture a degree of the transformative and experiential dimension of Belson’s work, an expanded cinema approach in step with the gnostic pursuit of knowledge and experience outside the ordinary.

Gnostic Cinema: Jordan Belson and Beyond screens tonight, July 24, at Spectacle.