It is no surprise that I have a special interest in Latin American cinema as a Latin American myself—how cliché, a man from Mexico with an interest in cinema south of the border. For the last two years, I have attended the Cinema Tropical Awards in an effort to remain aware of what’s on the horizon, and for the last two years I’ve come away with an excitement for films that rarely turn up in New York. If they do, it’s usually as part of some special one-night screening—typically, through the hard work of the folks at Cinema Tropical, who have been championing Latin American film old and new across the world for the last 15 years. The dearth of Latin American film programming in New York is nothing new; yet, I must write about it.

The confluence of items that force me to write this piece at this time is rather strange: an admittedly pedantic gripe with a now-resolved programming note, the Museum of Modern Art’s fantastic tribute to the Mexican actress María Félix, and a sudden email from a writer who has taken it upon himself to translate Argentine film literature into English. So, here it goes.

A little over a month ago I was scrolling through Film Forum’s website and reading the “PROGRAMMING NOTE” for their one-week run of Roman Polanski’s An Officer and a Spy (2019). (I’ll leave commentary on this film and its presentation to a more learned critic, as I’ve yet to see it and detouring into an essay on Polanski would veer this piece entirely off-course.) The note’s first two sentences read: “AN OFFICER AND A SPY premiered at the 2019 Venice Film Festival and subsequently opened theatrically in Europe, Mexico, and Russia. This is its first screening and theatrical run in North America.” What struck me was what at best was a simple geographical honest mistake, and what at worst was a clear removal of Mexico from North America. Google rebranded “The Gulf of Mexico” as “The Gulf of America” not too long ago in lockstep with our president’s America-first mentality, so the idea that people no longer believed Mexico to be part of North America did not surprise. That said ideology, actively exercised or casually manifested, propped up in New York’s film programming world also did not surprise me; after all, it is my suspicion that for many cineastes, Mexico, like the rest of Latin America, does not exist. And, to resolve this anecdote and avoid a poor parody of Baudrillard, I must note that Film Forum has since fixed their programming note. Moreover, their recent presentations of Victims of Sins (1951) and Luis Buñuel’s Él (1953) point to a brighter future as far as programming Mexican classics goes.

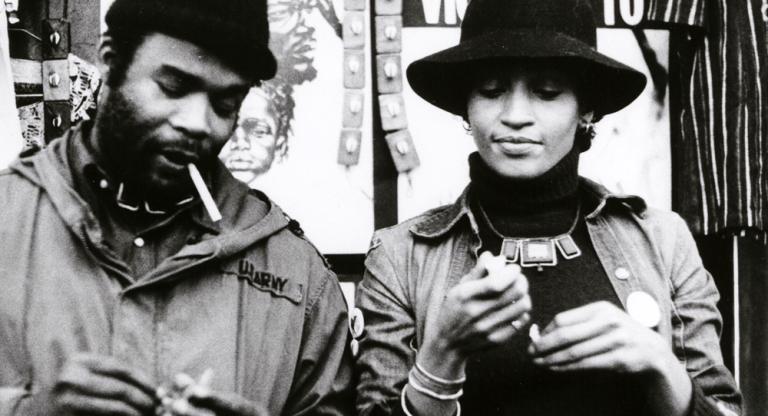

At MoMA, Dave Kehr and Steve Macfarlane (also a friend and fellow Screen Slate contributor) teamed up with Daniela Michel and Chloe Roddick of the Morelia International Film Festival to present a wide-ranging retrospective dedicated to María Félix. She was an actress, but above all else, a force of nature. Her bravado is of an era lost to time, akin to that of such silver screen stars like Marlene Dietrich. Seeing the films she starred in one after the other, night after night, conjured feelings larger-than-life, prompted by Félix’s gutsy, provocative performances. There’s no need to delve into the nitty-gritty of each film I saw at this retrospective, but I’d like to single out Tito Davison’s Doña Diabla (1950, pictured at top), also known as The Devil is a Woman. With a perfect 98-minute runtime, Davison’s lean moral fable about a woman who confesses to a life of sin after committing a murder is the twisty kind of cheeky melodrama that cameras were made for, a rat-a-tat of indecent encounters and emotional outbursts. That energy, sustained in Félix’s incredible ability to transform an intimidating look into an intimate glance with a furrowed brow and the cock of her chin, coursed through the retrospective. To see such a great performer is a rare treat, and to think local filmgoers might’ve missed this series is a true sadness.

I’d like to note that Kehr and company were also behind the “Buñuel in Mexico” series last year and the “Mexico At Midnight” series from 2015. This sort of dedication is admirable, and what’s great about a series like “La Doña” is that it not only offers a look at a career full of terrific performances, but to a neighboring film culture that evolved alongside its stars. “La Doña” was comprised of spy thrillers, national epics, bawdy thrillers, and heartfelt romances, offering a kaleidoscopic representation of Mexican film, which is so often reduced to Sergei Eisenstein and “The Three Amigos” (Alejandro González Iñárritu, Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro). Similar generalizations burden the rest of Latin American cinema, which is often political to a fault, highstrung, or so allegorical it’s alienating. Such general remarks arise from what’s been a sustained and limited encounter with a whole breadth of cinema for decades: cursory glances at its industrial milestones, such as the Argentine or Mexican Golden Age; an obliviousness to the New Waves that sprung up alongside The French New Wave in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and frankly all over; and a shrugged shoulder at what I’d argue is some of most exciting cinema in the world right now, whether we’re talking about Camilo Restrepo, Kiro Russo, El Pampero, Tatiana Huezo, or Nelson Carlos De los Santos Arias. There was not a single Latin American film in the Sight and Sound Poll from 2022, and Pepe (2024) didn’t get theatrical distribution in the United States. Latin America doesn’t exist.

Meanwhile, in Latin America, FestiFreak in Argentina is hosting an all-celluloid retrospective dedicated to singer, actor, and director Leonardo Favio; Malba celebrated the director Leopoldo Torre Nilsson’s centennial last year; I attended a comprehensive Paul Leduc retrospective at FICUNAM last year; Chile’s Valdivia Film Festival—to my knowledge—is the only festival in recent months that has stated they will not accept any films from MUBI in solidarity with Gaza. And these are just a few examples of the tremendous repertory programming going on in brethren nations that seem increasingly remote under this xenophobic administration. There are countless issues related to archives, rightsholders, subtitles, prints, and, to sum it all up, money involved in showcasing Latin American cinema in New York, but those same issues pervade the entire world of film programming. That such an important Argentine filmmaker’s centennial would go unmentioned, that it’s not until a few months ago that a Glauber Rocha restrospective was hosted in the city, or that Narcisa Hirsch’s films have only started popping up in New York now, is embarrassing.

I’d like to imagine there’s some change on the horizon. After Cahiers du cinéma named Trenque Lauquen the best film of 2023, there was an upward interest in Argentine film and film criticism. Over here in New York, Cinema Tropical has teamed up with Anthology Film Archives to present a new series, “Lost & Found: Cine(ma)s Latinoamericans Re-Unidos,” to highlight contemporary Latin American cinema, and efforts like those of the Latin American Film Center push interest in filmmakers like Arturo Ripstein and Felipe Cazals, marking a pivot away from the Mexican Golden Age and toward the exciting terrain of its New Generation in the ‘70s. Yesterday, three Latin American films were revealed as part of NYFF’s Main Slate: Lucrecia Martel’s long-in-the-works Landmarks (2025), Kleber Mendonça Filho’s The Secret Agent (2025), and Milagros Mumenthaler’s The Currents (2025). How these are received, we’ll see, but with such great names attached, the promise is exciting in itself. On a more personal note, I received an email from archivist Mike Yates, who has recently started a Substack translating Argentine film literature to English. His first article, about Hugo Cortázar's relationship to cinema, was fantastic. Perhaps his efforts signal an emergent interest in other corners of this dismissed heritage—in the writings of Teo Hernández, the directorial career of Valeria Sarmiento, the poetry of Claudio Caldini, and the work of active film critics between Mexico and Cape Horn, just to name a few things that warrant their rightful place alongside that cinema which has become so familiar on the rep circuit.

Feedback Loop is a column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City.