About a month ago, I came across an Instagram post announcing the creation of the Midtown Cultural Alliance, a new initiative set up between Japan Society, The Korea Society, Korean Cultural Center NY, L’Alliance New York and Scandinavia House. Its aims appear to be to 1) encourage more people to travel to Midtown, 2) increase visitor numbers at the aforementioned institutions, and 3) incentivize the regulars at one member of the alliance to visit its kindred. The initiative is new, and while all I really know about it is that it exists, it did make me think about how I have found myself attending more and more screenings at cultural institutions in recent months. Much of this might have to do with the fact that I now find myself closer to Midtown in the evenings, when I’m getting out of work, than in previous years, but I’ll also venture to state it reflects the adventurous programming that’s being put on by programmers at venues like Japan Society, L’Alliance New York, and Asia Society.

Around the same week said post had been made, I headed out to see Shinji Aoyama’s Eureka (2000) at Asia Society for the first time. The film was presented as part of “Dennis Lim Selects” following a screening of Raya Martin’s Independencia (2009) earlier that day. And, its presentation appears to have inspired a resurgent interest in the film, which is now screening at other venues across the world. It’s a bleak and beautiful film, thoughtful and hypnotic, incredibly precise but also freewheeling. As far as I am aware, it had not screened in New York since its initial festival run around the turn of the millennium. Praise is in store for Dennis Lim’s suggestion to program it, as well as Asia Society’s Curator of Film Inney Prakash for awarding the time to show such an expansive and overlooked work.

“I’ve been here for about a year and have been able to show popular work in our theater, but also to be adventurous and really lean into Asia Society’s identity as a museum and cultural space,” said Prakash in a conversation we shared over the phone. Since he joined the institution, Prakash has shown films by Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Adoor Gopalakrishnan, among many others, on 35mm, in addition to organizing a retrospective dedicated to Ang Lee, whose work is often both popular and adventurous (see fellow writer Patrick Dahl’s piece on Hulk for example.) Now, in about a week, he’ll be showcasing the work of the experimental filmmaker Joshua Gen Solondz at Asia Society. “Showing this all-out, hypnagogic work in a 250-seat auditorium will make for a unique experience,” he told me. And, in a month or so, Asia Society will be teaming up with Anthology Film Archives to present five films by the Uzbek filmmaker Ali Khamraev, whose work has been celebrated by critics such as Kent Jones but remains underseen in the United States. This is daring programming, privileging the under-explored and urging audiences to step outside of what is firmly considered canonical.

A similar interest in the overlooked motivates Jake Perlin’s film programming at L’Alliance New York, where he is presenting not one, but two retrospectives this Fall — in addition to numerous other programs, like his new series focused on restored Francophone productions and a New York iteration of Cannes’ Quinzaine des cinéastes. Speaking to the first of these retrospectives, which is being dedicated to Sophie Fillières, who passed away in 2023, Perlin stated that he was not just interested in organizing retrospectives around mid-century filmmakers, but also for figures whose work has not been rightfully celebrated in more recent decades. The series he organized around André Techiné and Catherine Deneuve’s collaborations, for example, was comprised of titles from the ‘90s. And this upcoming iteration of Quinzane des cinéastes here in New York gestures at an interest in the future of cinema. Having seen both Gaston Modot’s silent masterpiece Cruel Tale (1930) and the exceptional Moi-Même (2024) at L’Alliance New York, I can attest to the fact that notable cinema, both old and new, is being shown at the venue on a week-to-week basis.

The second major retrospective taking place at L’Alliance New York this Fall/Winter is the second part of their tribute to Yannick Bellon. “I cannot overstate how great Yannick Bellon is,” Perlin told me. “My colleague, Chloe [Dheu], and I are very committed to getting her work seen.” I have not seen all of her work, but I believe him based on what I’ve seen. Films like Somewhere, Someone (1972), Nevermore, Forevermore (1976), and Remembrance of Things to Come (2001) demonstrate a rare degree of observation that manages to both communicate the magic of a passing moment, and how such brief periods of time hold in them the weight of history — both personal and political. This conclusion to L’Alliance New York’s celebration of her work should not be missed. Nor should Japan Society’s exciting new program “Shiguéhiko Hasumi: Another History of the Movie in America and Japan,” which offers New York audiences with an opportunity to engage with another overlooked figure, at least in the United States.

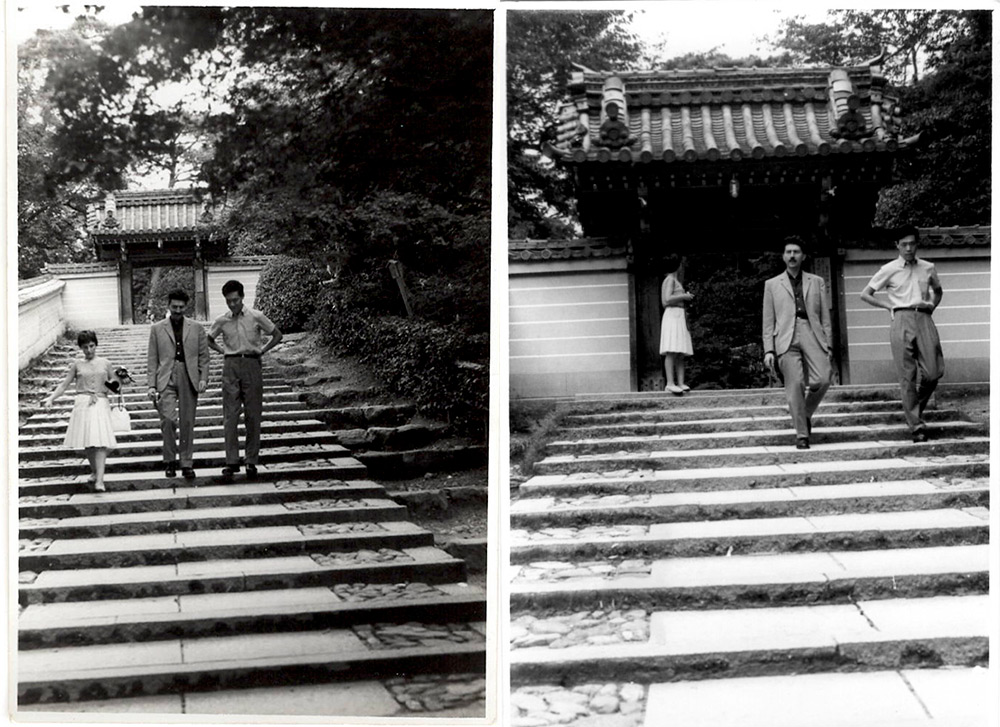

Shiguéhiko Hasumi (pictured at top with Alain Robbe-Grillet) is a cultural titan in Japan, having helped introduce the theories of French philosophers like Michel Foucault and Giles Deleuze to Japan in the ‘70s, in addition to influencing a lineage of filmmakers that includes Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Shinji Aoyama, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, and Sho Miyake, among many more. His omnivorous approach to cinema lends the series its multitudinous dimension, which in turn reflects Hasumi’s belief in a cinema culture that considers arthouse cinema in the same way it does popular fare. “Hasumi’s approach to film was not snotty, he saw B- and A-movies on the same plane,” Alexander Fee, Film Programmer at Japan Society, said to me. “Since we’re talking about the ‘70s, this included the roman porno, which he saw the same way as any arthouse film.”

His openness to films of all sorts also informs his love of international cinema, but, more to the point apropos of this series, his fondness for American cinema. “This was an opportunity for Japan Society to not just show Japanese films; for example, Hasumi has written extensively about Michael Mann and championed him, and that’s one of the reasons we’re showing Collateral,” said Fee. Other American titles in the mix include Nicholas Ray’s They Live By Night (1948), Richard Fleischer’s The Boston Strangler (1969), John Ford’s Kentucky Pride (1925), and Robert Aldrich’s All the Marbles (California Dolls) (1981). So, for an audience that has perhaps dismissed (or not had the chance to engage with) Japanese film scholarship, Fee has packaged a perfect little introduction that seeks to recontextualize people’s understanding of the crosscurrents between Japanese and American film culture.

General impressions consider spaces like Japan Society, L’Alliance New York, and Asia Society as spaces of “cultural immersion,” sites where the taste of another nation or set of territories is simply displayed. But, whatever limited view of these institutions exists in the cultural imaginary, it is impossible to deny that the aforementioned film programmers are assembling some of the most adventurous programming in the city right now, challenging and building upon people’s understanding of what Japanese, French, and Asian cinema can be.

Feedback Loop is a column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City. Thanks to Alexander Fee, Inney Prakash, and Jake Perlin.