Love is sinister. Struck by its dumb side (the most frequently striking), lovers will always choose to play its twisty two-person games instead of paying heed to the rooms in which they romp—with walls papered, from fraying ceiling to floorboard, by unavoidable Politics. The lovers’ eyes pass over one another’s bodies; their minds ignore the outside light, smog-choked and ashy and fatal, that invades the windows and casts a gray pallor over their skins. Love is sinister. How many times will we forget this basic fundamental human fact? How many times will it be re-learned?

Those questions are at the core of Fabian: Going to the Dogs (2021), the latest depressing jaunt from Dominik Graf, the craftsman today working closest to the quick-turnaround gait of a Mervyn LeRoy. (Graf cut his teeth in German television instead of ’30s Warners.) Despite a three-hour runtime, this is a simple (“simple”) film which comes out of a TV tradition: rudimentary, unflashy, plain, brisk. Graf avoids pat fanciness, prefers the most basic of camera set-ups, disallows his actors from wandering into the weeds of Style. This manner of working is not a post-post-modernist gambit to reflect Fabian’s source material, the 1931 novel of the same name by Erich Kästner. Rather, it’s Graf’s lifelong, steady desire not to make his viewer feel like his vast, rollicking work is anything special.

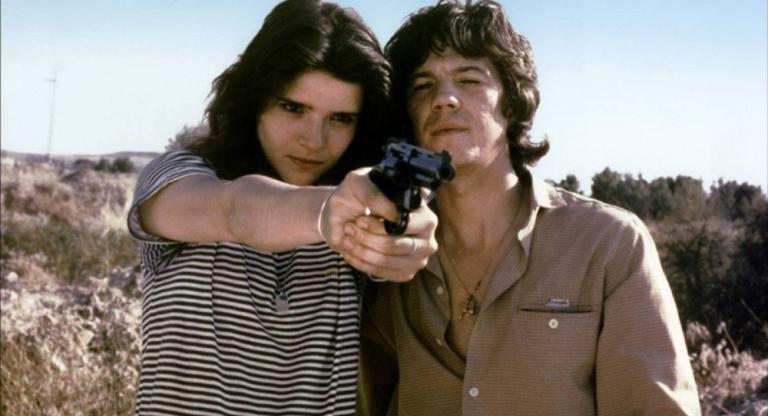

The original title of Kästner’s novel was Fabian: The Story of a Moralist; here, the subtitle becomes Going to the Dogs, which is how one dumb, cruel character (a “moral,” right-wing nut of a mediocre professor) describes what’s happening to humanity in the Weimar days in which the story is set. This professor believes tomorrow belongs to decent, upstanding gents like him—and certainly not the titular Jakob Fabian (Tom Schilling), an aspiring avant-garde novelist and man-of-letters who is merely in the business of surviving. (It’s Berlin, 1931.) Politically, Fabian is middle-of-the-road, but he’s got good ideas, as his staunchly leftist, best friend Stephen Labude (Albrecht Schuch) believes. In a dingy, grotesque cabaret one night (it makes the KitKatClub look like Critter Country), Fabian meets Cornelia (Saskia Rosendahl), an international film lawyer. They embark on a whirlwind love affair, as questions and sentiments pile up over the flaming hell into which German society is nose-diving. The lovers simply want to love—he wants to write mad prose, she wants to be the next Dietrich or Pola Negri. The best friend wants to change hearts and minds, all while writing his extremely promising thesis on Gotthold Lessing. But looming around the corner are the Reichstag Fire, Kristallnacht.

Graf frontloads the movie with weird, unstable, inconsistent tricks: jump-cuts, a sped-up herky-jerk rhythm that feels like a hand-cranked silent film, ugly split-screens inside a club. We have the rhythms of cinema that were absorbed by novels of the ’30s, like John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy, now returning, in safe period form, to the service of a TV-like drama (at the Metrograph, you’ll feel like you’re bingeing a solid miniseries) set amidst the ruins of German interwar memory. Fabian eventually settles into a conventional-yet-addicting pace following the fabulously bad luck of Fabian as he’s dismissed from job to job for being too arty and struggling to clarify what it is, exactly, that he does. “I observe,” says Fabian. “Who does it help?” asks Labude, the lefty bestie. “Who can be helped?”

Not much is done, in terms of sets or easy signage or the psychological space occupied by the actors, to absorb us into an atmosphere that reads instantly as Weimar. Just a few blips of props and costuming will do for Graf: fading jacket here; sailor-girl’s cap, unshaved pits, and icy Dietrich glances there—all to more efficiently reroute the Caligari-to-Hitler pipeline into today’s age of what I’ve called the Clean Stream (our current sanitized streaming landscape, in which characters live without mess, edge, or unmanageable desperation). Fabian is caught up in a beguiling pessimism perfect for our own decrepit day, from its fog-choked opening inside a 2020 Berlin metro station up to its brutal ending—which, for many, will be one cruel coincidence too many. For me, it is exactly the way modern life works; it is “real but it eschews formalism,” as Fabian describes his planned novels. The image of a lover waiting inside a café for the other to arrive—dressed to the nines in silky white, drinking espressos until they’re bored, returning the next day to repeat the whole pathetic ritual, blissfully unaware of what happens outside those four white walls—will, sadly, never leave me. “The wrong people lived, and the wrong people died . . . ” The only possible response to these miseries? Labude: “Write. Write it how it was . . . and how it could have been.”

Fabian: Going to the Dogs screens through Thursday, February 17, at Metrograph.