For all the decades of lament over the death of cinema, 2020’s slowing of the endless torrent of new releases has provided a few silver linings. With the Hollywood-hype machine on full hiatus and the creaky churn of festival buzz ground to a halt, it’s high time to explore all the nooks and crannies of cinema’s past. The subject of a new program of restorations streaming for the benefit of Film Forum, silent-era clown Charley Bowers is just the sort of figure who’s ripe for rediscovery.

While Chaplin may be famous for getting caught in the machine of industrialization and Keaton for personifying the mechanized, impersonal shocks of the factory assembly line, Bowers’s persona is unique in its sincere embrace of the machine’s possibility. For Bowers’ wide-eyed naif, the machine age was less a cloud of technological oppression than a site of juvenile discovery and everyday invention. Known in France as Bricolo (which translates to “tinkerer” or “handyman”), Bowers usually cast himself as some sort of amateur crackpot inventor tasked with finding solutions to problems no one needed solved.

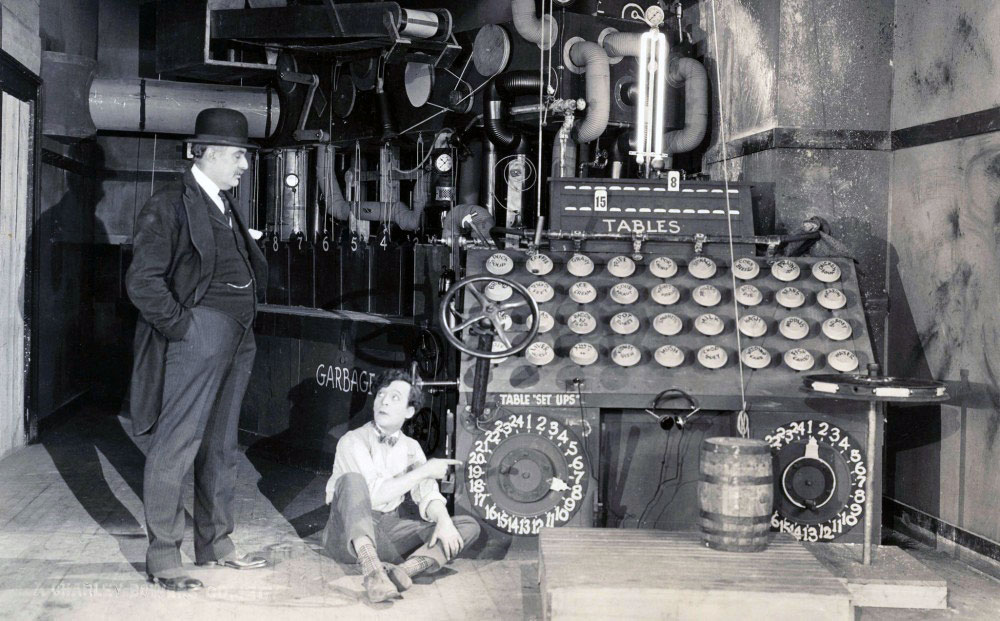

Given to crafting large machines out of household junk — everything from a bird cage to an old man’s beard — it’s no wonder that Bowers was beloved by Andre Breton and his fellow surrealists. From the machine designed to craft unbreakable eggs in Egged On to his tireless search for a chemically-crafted slip-proof banana peel in Many a Slip , Bowers’s comedy turns the 20th century obsession with progress into a comic fairy tale. Even when his madcap devices are engineered for a more rational purpose — such as in He Done His Best , in which he manufactures a robotic waiter/chef after inadvertently causing a strike in his sweetheart’s father’s restaurant — his stop-motion automatons and naive romantic attachments give the proceedings childlike sense of wonder.

Moving from circus stardom as a six-year-old to working as lead animator of the popular ‘Mutt and Jeff’ series of the 1910s before landing in live-action slapstick, Bowers was a multifaceted entertainer who synthesized his talents in a manner wholly his own. His variety of skills is perhaps best showcased in There It Is ,wherein Bowers plays a Scotland Yard detective tasked with fighting an egg-headed ghost grandpa unleashing anarchic mayhem in a New York mansion. By far the most physical of his roles featured in this collection, Bowers’ detective runs around the house somersaulting over furniture while his rollerskating nemesis, the Fuzz Faced Phantom, pops in and out of the frame from every direction at once. Enlisting the help of his two-inch tall scrap-metal sidekick MacGregor, Bowers catches the ghost yet still ends up penniless.

While the endings of Bowers’s films might strike a more pessimistic tone than your typical slapstick two-reeler — he almost never gets the girl and his gizmos generally combust — his amateurish ingenuity is nothing short of uplifting. With quite a lot of us still stuck at home these days, it’s hard not to feel some primal delight at the sight of so much bric-a-brac transfigured into all manner of quixotic innovation.