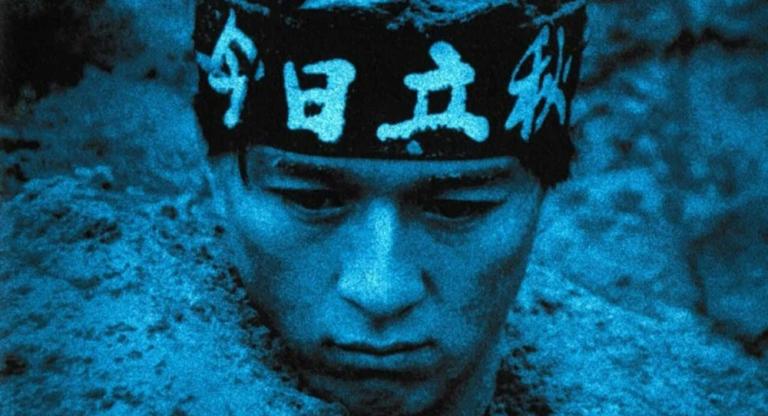

Cobra Woman (1944) is a fabulous anomaly in the career of its director, Robert Siodmak. Largely known for noir films and thrillers, such as The Killers (1946), Criss Cross (1949), and The Spiral Staircase (1946), with Cobra Woman Siodmak fashioned the supreme star vehicle for “The Queen of Technicolor,” Maria Montez. It remains the most famed contribution to the series of wonderfully dopey, candy-colored adventure films which made Montez famous. In this one, Montez plays two roles: the exiled princess Tollea and her twin sister Naja, deranged dictator of Cobra Island, who dances with a cobra while selecting from her audience of terrified onlookers those who will be hurled into a flaming volcano. Unusual as the film may seem for its director, Andrew Sarris devotes roughly a third of his entry for Siodmak in his 1968 handbook of auteurism, The American Cinema, to Cobra Woman, which he blames for “spawning” underground films like Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963).

The importance of Montez—and of Cobra Woman in particular—to many of the leading queer artists in postwar America is undeniable. Kenneth Anger declared Cobra Woman his favorite film. Charles Ludlam, Ronald Tavel, and John Vacarro all venerated Montez, quoting from Cobra Woman in their work and in their lives. Gore Vidal was also fascinated by Montez, who features prominently in Myron (1974), his unaccountably underestimated sequel to Myra Breckinridge (1968). But her most devoted acolytes were undoubtedly Jack Smith and Mario Montez, who appears in Flaming Creatures and took his drag name from Cobra Woman’s star.

The Boricua drag queen Mario Montez was often the only person of color in an overwhelmingly white New York underground scene, working with Smith, Ludlum, Ron Rice, and Avery Willard (as well as Latin American artists Hélio Oiticica and José Rodríguez-Soltero) and becoming the first drag “superstar” in the Warhol Factory. His interest in Maria Montez likely went beyond her camp value, although that was certainly part of the appeal. The Dominican actress, along with her frequent co-star, the Indian American actor Sabu, starred in enormously popular films that were, for the most part, not about white American or European people.

This is not to say they were not full of ridiculous, even offensive, notions of the “exotic.” White actors in brownface frequently appear alongside Montez and Sabu, and the films take place in vague, non-Western neverlands that might be a strange tropical island (as in Cobra Woman) or a ludicrous Orientalist fantasy (as in 1942’s Arabian Nights). But, as Agosto Machado, downtown theater legend, “pre-Stonewall street queen,” and confidante to Mario Montez, explained when he screened a Maria Montez film for Queer|Art|Film in 2017, seeing Montez and Sabu in these far-flung fantasies could be momentous for a young queen of color. Indeed, the late scholar of performance studies José Esteban Muñoz traced the influence of Maria Montez and what Sarris called her “deliriously defective” approach to acting to the development of performance art, not only through Jack Smith, but also artists and performers such as Carmelita Tropicana, Vaginal Davis, and Nao Bustamante.

Montez often felt she was ill-served by Hollywood and her primary studio, Universal, which she blamed for press which made her appear delusional and narcissistic. Maybe she was a narcissist, and if she was, who could blame her? She has frequently, infamously, and perhaps apocryphally been quoted as saying, of watching herself on screen, “When I look at myself, I am so beautiful I scream with joy!” See Cobra Woman and ask yourself, how could she not?

Cobra Woman screens tonight, April 7, at Metrograph on 35mm as part of the series “Robert Siodmak x8.”