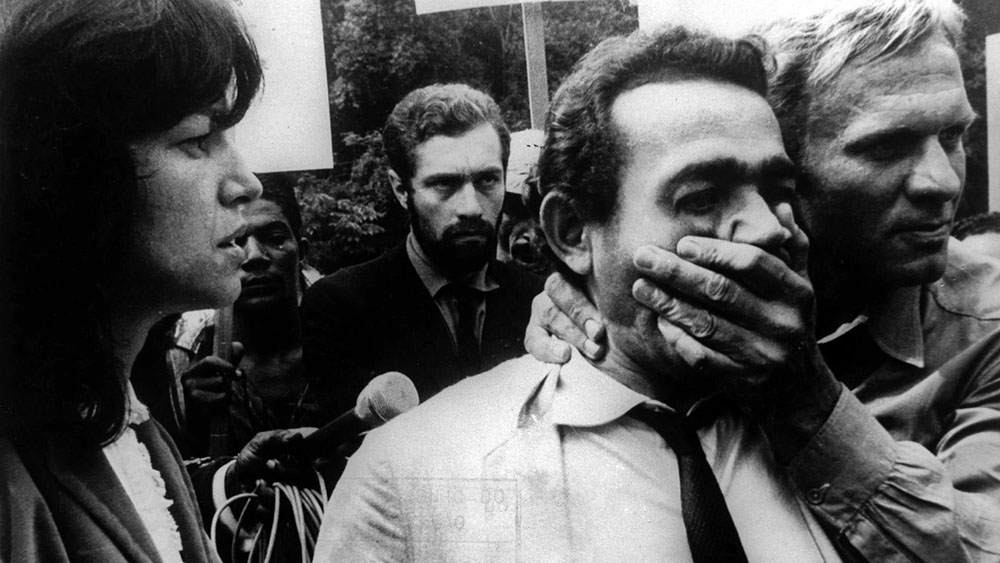

At the start of Glauber Rocha’s Entranced Earth (1967), a young writer yells, “My madness is my conscience!” as he drives through a police barricade. In the dying man’s oneiric flashbacks, his allegiance sways between a right-wing mystic and a liberal pseudo-reformer, both vying for control of the fictional South American country Eldorado. The camera makes delirious revolutions around its subjects. Produced during the early years of Brazil’s military dictatorship, Rocha’s film exemplified Cinema Novo’s fierce challenge to Hollywood and its insipid imitators. Their “aesthetics of hunger,” Rocha stated in his 1965 manifesto, was misunderstood by Europeans as mere “tropical surrealism.”

Entranced Earth is one of eighteen astonishingly varied films in “‘Be realistic, demand the impossible!’ Cinema, Surrealism, Marxism,” at BAM, programmed by Yasmina Price and spanning 1929 to 2018. The directors (working in India, Brazil, France, the U.K., Czechia, the Soviet Union, Chile, the Netherlands, and Mexico) diverge in their relationships with Marxism, but a common thread is a rejection of clarity and doctrine, a search for new filmic forms, and a desire to make films politically. With exuberance, absurdity, and digression, the most exciting of these films run counter to the persistent melancholy of the left.

Surrealism’s task, per Walter Benjamin, was “to win the energies of intoxication for the revolution.” The Paris Surrealist circles of André Breton et al. had a fraught relationship with Marxism in part because of the perceived dissonance between Freudian transcendentalism and Marxian materialism. Price’s program proposes that the expanded, global legacy of surrealist cinema is propelled, to this day, by insurrection and disruption. If Surrealism originated, in Benjamin’s words, in “the damp boredom of postwar Europe and the last trickle of French decadence,” its spirit and discoveries found new life in militant and experimental cinema, transformed in a global anti-colonial context to forms exceeding its original bounds.

“Cinema, Surrealism, Marxism” opens with Isaac Julien’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1997), the first of many essay-films in the series. Combining reenactment and archival footage, it is a dream-like meditation on the life of Fanon and the ongoing reverberations of his work (today, Fanon is often invoked in the struggle for liberation in Palestine). Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) is a treatise on revolutionary desire, the beauty of youth, and the color red, an entrée into the program’s emphasis on anti-imperialism and the global south: Godard’s Maoist cell features Omar Blondin Diop, a young writer and revolutionary who would die in a Senegalese prison in 1973. In Bengal, director Mrinal Sen responded to Godard and Cinema Novo with a trio of “city films,” including Calcutta 71 (1972), in which a young man, eternally 20 years old, cycles through debasement and death (Sen opens the film with newsreel footage, set to acid rock).

Pleasure and excess drive Věra Chytlová’s Daisies (1966), a sparkling, anti-patriarchal tale of two young friends named Marie who, noticing that “everything is going bad in the world,” decide to have fun. Their defiant romp includes food fights, arson, and a destructive approach to fashion (Chytlová was a former model), with psychedelic visual effects. Czech sensors allegedly didn’t know what to make of the film and banned it for wastage of food. Chytlová called it philosophy in the form of farce.

Another gem is Raúl Ruiz’s hilarious On Top of the Whale (1982). Where Chytlová used farce to highlight the absurdity of men and society, Ruiz’s satire skewers ethnography and cultural imperialism. In a future Netherlands Soviet Republic, an anthropologist receives an invitation from a suave “Communist millionaire” to study the last speakers of the fictional Yachenes language in Patagonia, which allegedly consists of a single word (the film’s title references Borges’s Book of Imaginary Beings). Ruiz shot On Top of the Whale in a week without a script, and had the actors talk in five languages. Color filters saturate shots at random. As with many films in the program, it is about and of displacement; after Pinochet’s 1973 coup, Ruiz fled Chile for Paris. His fabulist low-budget films drew inspiration from Hollywood B-movies, and On Top of the Whale satirizes the European fetishization of primitivism—a fixation of many Parisian Surrealists.

Seven years after Guy Debord wrote the Situationist classic The Society of the Spectacle (1967), he adapted his text into an essay-film of the same title. The groundswell of 1968 had passed in France and, in a “détournement of preexisting films,” Debord assembled a vertiginous montage of quotations and images that overwhelms the original text. Debord pulled the film from circulation in 1984; despite the book’s fame, it is rarely screened. Its presence here suggests détournement as an operation of special note across the program. The Society of the Spectacle and Chris Marker’s epic A Grin Without a Cat (1977) are both mosaics that work through historical memory as a tide of images and sounds. For Marker, who originally titled his film “Le fond de l’air est rouge,” student movements and Third World uprisings (and the countless reels documenting them) become a dream viewed through a red filter, whose meaning and energy lie in its radical incoherence.

Luis Buñuel is the program’s only concrete link to surrealist cinema proper. In his raucous late works The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and The Phantom of Liberty (1974), symbols are abused to the point of absurdity. Buñuel wrote Liberty from a dream journal, and he seems to turn cinema into automatic writing as digressions and images devour plot: an emu struts through a bourgeois Parisian flat, friars smoke and gamble, and a postcard of Montmartre is transgressive pornography.

One screening pairs the series’s two earliest films: Dziga Vertov’s ecstatic Man with a Movie Camera (1929) and Alain Resnais and Chris Marker’s Statues Also Die (1953). Vertov’s unlikely presence makes me realize that his approach sits as close to Godard’s and Rocha’s as do those of his fellow Soviet monteurs, Eisenstein and Shub. His explosive combination of eye and machine anticipates the Surrealists’ biomorphism, and he celebrates the streets of the revolutionary city (filming in Moscow, Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odessa during the early years of the Soviet Union) as sites of strange and aleatory encounters.

Collective production defines the program’s 21st-century films. The Sun Quartet (2017), by the anonymous Mexican Colectivo Los Ingrávidos, reworks found footage and documentary conventions to protest the disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College. It will screen with Be Silent, For The Ears of God Are Everywhere (2018), a celebration of vinyl records and collective spaces by the Otolith Group, a joint project between Londoners Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun. In Communists Like Us (2010), a film which began as a performance, Sagar and Eshun détourn archival images and a clip from La Chinoise to work through revolutionary nostalgia. It’s good to see their work shown outside of contemporary art venues; in their myriad practices across performance, research, and film, they propose ways of finding political possibility through displacement and dissonance.

“‘Be realistic, demand the impossible!’ Cinema, Surrealism, Marxism” runs November 10–16 at BAM.