The Zodiac Killer technically only terrorized the San Francisco Bay Area for less than one year (1968 - 1969), but the serial murderer’s impact on American popular culture has been significant, especially in cinema. He has inspired fictional killers in Dirty Harry (1971), The Exorcist III (1990), and Seven (1995), as well as slasher films like The Zodiac Killer (1971)—its director, Tom Hanson, claims it was actually a plot to lure the real killer to the movies—and, of course, David Fincher’s procedural mystery Zodiac (2007).

The Zodiac purposefully engaged with the news media, famously sending letters and ciphers to Bay Area newspapers, stoking fear in the public while also enabling them to join in on solving the mystery themselves. The amateur sleuthing that the murders and the media circus surrounding them inspired never really ended. A strong argument could be made that the Zodiac case, still unsolved to this day, launched the modern era of true crime.

The nonfiction filmmaker Charlie Shackleton noticed that despite the Zodiac’s cultural footprint, no documentary had risen to the top to become the canonical take on the subject. After a thwarted attempt at adapting The Zodiac Killer Cover Up, a 2012 book by former highway patrol officer Lyndon Lafferty, who had a peculiar, under-heard take on the case, Shackleton took the shards of the project and instead explored the idea of an unrealized work, as well as his love-hate relationship with true crime itself. The end result is the clever and unique Zodiac Killer Project, a cinematic exercise that conjures the impression of a film that the viewer will never see, while simultaneously offering a meta-dissection of true crime media.

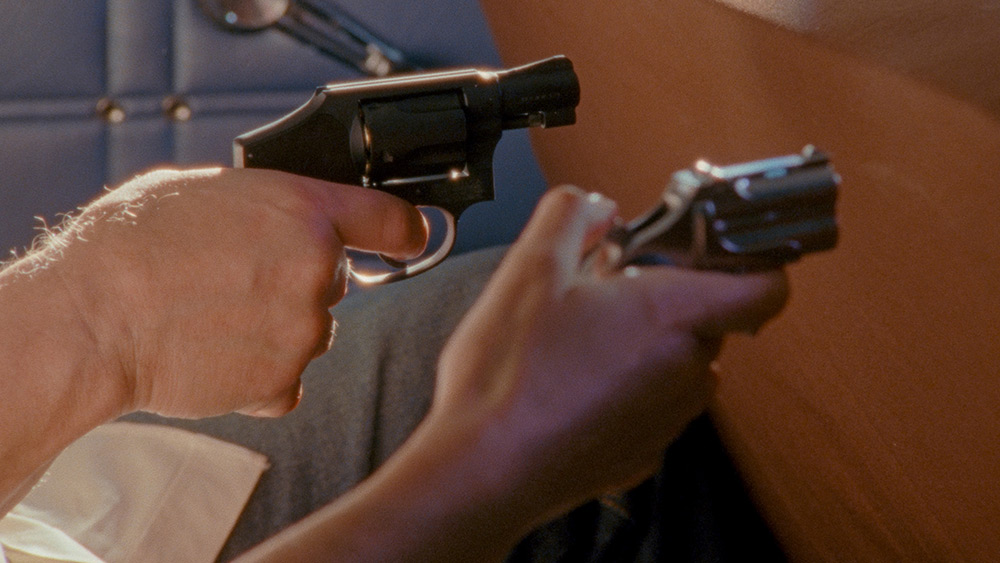

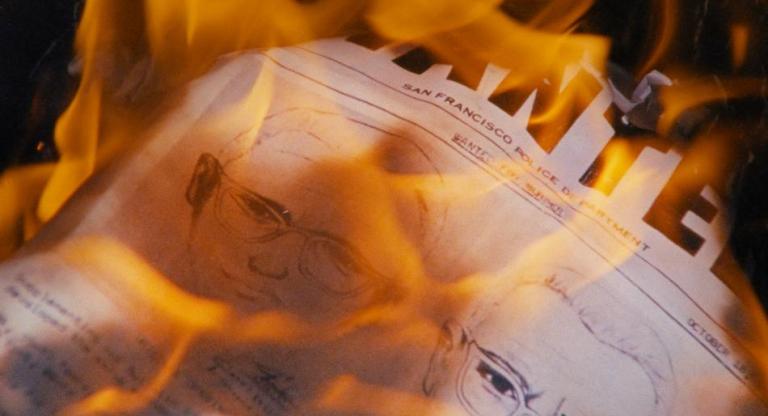

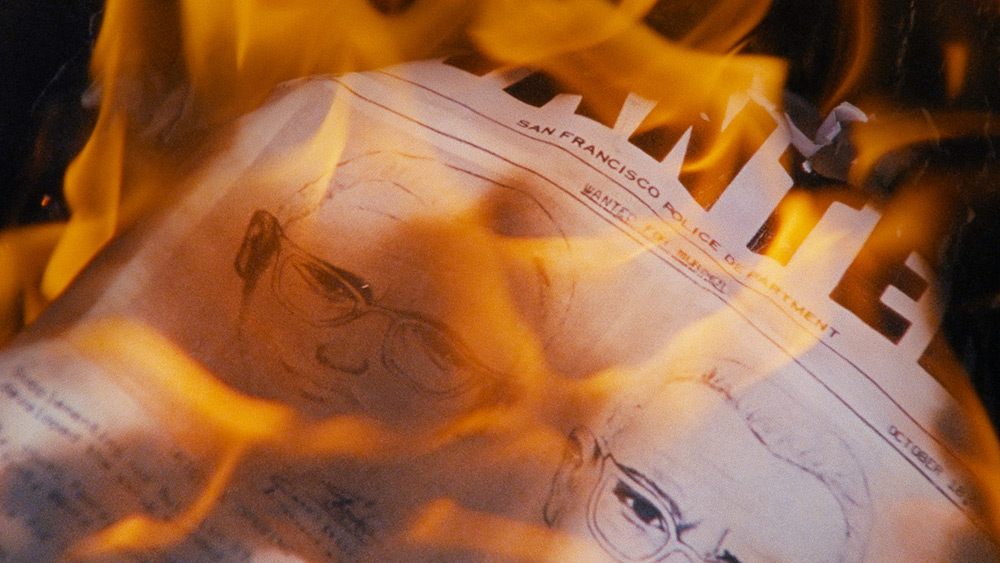

Shackleton has deconstructed genres in his films before, notably in Beyond Clueless (2014) and Fear Itself (2015), essay films that are comprised almost entirely of footage from existing teen/coming-of-age and horror movies, respectively. Zodiac Killer Project contains moments from well-known true crime series, which Shackleton uses to demonstrate how the visual tropes that characterize most true crime media films/series become tremendously cliché yet remain tremendously effective. However, the bulk of the film is composed of long shots of various Vallejo locations pointedly drained of their Zodiac aura, with Shackleton himself describing the would-be documentary through voiceover. Various inserts of “evocative B-roll” flesh out the rest of the narrative, transforming visual language that has become a staple of the genre into something unusual and dreamlike.

I spoke with Charlie Shackleton about how he transformed an unresolved project into a compelling piece of art, and about making nonfiction film in a media landscape oversaturated with true crime. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Stephanie Monohan: My understanding is that you were rather deep into pre-production on the original project before Lyndon Lafferty’s estate decided to retain the rights to his book. How did Zodiac Killer Project emerge from that?

Charlie Shackleton: The origin story of the project, essentially, is that I committed the cardinal sin of filmmaking. I did loads and loads of work before I had the rights required to make the project. All of that work was basically in my own head: conceptualizing the film, mapping it out, structuring it, envisioning all of these scenes that I go on to describe in Zodiac Killer Project. When they pulled out of the negotiations to the rights to the book, I was devastated because I had done all that work. But, it’s certainly not the first time I’ve had a project fall apart in the early, or even the late stages.

Usually, I lick my wounds for a month or two and then, maybe, take some small elements of an idea and reapply it somewhere else. For whatever reason, it was this project that refused to die. I found myself back here in London describing it at length to friends. We’d be sitting in pubs and I would be, beat-by-beat, acting out the film. At a certain point, that itself started to seem like an interesting subject for a film, long before I even necessarily envisioned it as a critique of true crime or something that would have a broader scope. I really just thought it could be interesting to make a film about an unrealized and unrealizable creative ambition, and I was also drawn to the formal challenge of conjuring the sensation of a film that I can’t actually make or show anyone.

SM: What do you think it was about this project in particular that stuck with you?

CS: This is probably the first project where I really felt the thrill of adaptation, because the book is filled with these incredible narrative twists and turns, and really striking images and unexpected scenes that you really don’t see coming in a telling of the Zodiac Killer case. But, it’s also incredibly dense and filled with information that could never possibly work in a 90-minute true crime film. Even as I was reading the book for the first time, before I had ever mentioned adapting it, I felt like I was doing that process of adaptation and thinking, “That would make a beautiful image in a film.” The hands slapping the sides of the fishbowl and wiping the prints off, for instance.

By the time I got to the point of trying to license it, I felt I had this thing that was both the book and also a completely different thing of my own making. I was probably a little pleased with myself in having, with what felt to me, like such a great iteration of the book, but not a direct mirror of it at all. The rights falling through was the negation of that process.

SM: Is any of the footage in the finished film from that pre-production period before the rights fell through?

CS: We hadn’t shot a frame. All of the footage in the film is essentially trying to recreate the feeling I had going into location scouting. That was actually how me and the cinematographer, Xenia Patricia, arrived at the form of the film, specifically those mechanistic series of camera movements where it pans in and holds, zooms, zooms out. That was something we arrived at in discussing the uncanny feeling of location scouting a true crime film. You’re going to these places that you’ve heard of all these morbid, weighty stories about, and then you arrive and find really humdrum, ordinary places with people going about their lives. I remembered that sensation of standing, staring, and scanning for intrigue where there was none. That’s what we were trying to capture in going back and shooting all of them.

The little flashes of B-roll were all shot later in the studio, here in London, after the voiceover had been recorded. We shot those in direct response to what had come up organically in the process of the voiceover recording. The true crime B-roll was my little consolation prize to myself, allowing myself to shoot some of those images that I thought I never would.

SM: Do you have a favorite insert of “evocative B-roll”?

CS: In general, the ones I love are the ones that don’t quite make sense. There’s an image later on in the film of Lyndon, or rather, the stand-in for Lyndon, looking through a two-way mirror into what the narration describes as an interrogation scene. But on set we didn’t really have any of the things you would need to shoot that, so instead we just had our stand-in stare into a pane of glass and we captured his hazy reflection in this pane of glass, which doesn’t look anything like it would look if you were looking into a two-way mirror.

There’s something about the force of will of hearing a voice tell you that’s what you’re seeing, and then seeing an image that contains some of the elements of that idea. You just gotta buy it. I think this is what underpins so many of these clichés or trope-y images from this genre. They’re persuasion. They don’t really have to make logical sense, they just have to be close enough. If they’re delivered with confidence, you give yourself over to them.

SM: It reveals a lot about the constructedness of true crime that just by assembling images based on the stylistic conventions of the genre, it triggers an almost reptilian response that we have to certain stories and the way they're presented to us.

CS: Totally. That stand-in who was playing Lyndon, we only had him for one day, and we were shooting in that studio for five days. So on the days where he wasn't there, whenever we needed Lyndon’s hands to be performing some action or another, it was just my hands. And look at my incredibly skinny hands versus the hands of the actor who was probably twice my mass. It is a constant continuity error throughout the entire film, and yet not a single person has mentioned it to me or asked me about it. Because if you’re told it’s Lyndon’s hands and then you see hands, especially if you see them for just a second, you don’t question it. It gives you incredible leeway as a filmmaker.

SM: For a film about the absence of a film, where you’re essentially denied the material you need to make it, the dynamic you wind up creating out of static landscape shots punctuated by brief studio B-roll is actually very engaging. How did you approach conveying this unmade film to the viewer while controlling the tone and tension so tightly?

CS: I found a really satisfying challenge in the edit in that all of the visual material I had to work with was either very long and languorous or almost imperceptibly fleeting. We were shooting everything on 16mm. Each of those location shots was 200 feet long, and most of our studio shots were about a foot long. There was this real contrast at the center of the visual flow of the film, which was seeing how it felt to make a viewer sit with an image that’s almost static for 2 to 3 minutes, and then showing them something else for less than a second. For me, the pacing and dramatic value of the film was discovered in the edit and it was very stimulating.

In terms of conjuring the unmade film, it really did feel like most of that had to happen in the mind of the viewer. The images are certainly not getting you there. They’re almost showing you the antithesis of what’s being described. And the music by my composer, Jeremy Warmsley, sometimes offers the requisite drama or tension, but it does so in a very brute force way that you’re quite conscious of—it doesn’t exactly lull you in. It’s quite intentionally confronting you with the directive of how you should feel, before I fully come out and say it in the narration.

The challenge and the fun of it, for me, was to encourage people to conjure all of that for themselves in their minds, even as you’re telling them you’re doing that. I think the way that manifests is in a push-and-pull. Sometimes you’re in it and sometimes you’re hyper-aware of the forces acting upon you. That’s a very satisfying seesaw for me.

SM: Your recorded voice is present throughout the whole film, already contributing to a meta, or distanced look at the subject matter. Then, out of nowhere, we see you in the recording booth, and that distance widens even more. How did you decide when and how to reveal yourself onscreen?

CS: I like that it comes halfway through the film, because since there’s so little happening on screen, it can almost play like a twist: “Oh my god, a man! A man in a room! What a dazzling visual surprise compared to the shots of street corners I've been looking at for 45 minutes.”

Throughout the edit, I played with introducing that footage at various points, or not having it at all. When we shot it, we really weren’t sure whether we would ever need it or not. But the places it wound up becoming valuable were the places that invited the most self-scrutiny on my part. Even in a film that is inherently metatextual from beginning to end, there are moments where that inward-looking gaze became unavoidable. And you can often hear me trip up over my own words, because I’m identifying a tendency of true crime or documentary film in general, that I then realize I’m in the process of performing. I tried to be led by those moments of organic rupture, and let those lead to the formal ruptures that are happening on screen.

SM: I think those are some of the most compelling moments.

CS: It’s a very controlled film in some ways. I’m not only this orator telling you what to think about and how to feel throughout the entire thing, [but] you’re obviously aware I'm the person who curated the images you’re looking at and is in charge of the entire production. I think there was a real value to the moments where you hear me lose that power a little bit, or at least be challenged by the unavoidable contradictions of the whole project.

SM: If I could identify an emotional “climax” at all, it would be the scene immediately following the steakhouse dinner. Lafferty is getting a ride home from the man who he believes is the Zodiac Killer, but all we have are images of the headlights shining on the pavement as a car speeds down a dark road, combined with the music intensifying. This is an audiovisual combo we’ve seen in many films before, and everything up to this point has drawn the viewer’s attention to the almost comical prevalence of such images, but I still found myself lost in the tension of the moment. It’s like no matter what, the lost highway just beckons.

CS: It’s crazy, isn’t it? I’d love to take credit for that, but I think a large part of us just wants to be absorbed. It doesn’t matter how many times you pull the rug—by this moment, I must have done 25 rug-pulls, and it doesn’t matter. You just want to give yourself over to the drama of the moment. I do too! I still get caught up in the alchemy of the image and the sound.

SM: You have a very measured tone throughout the film when it comes to your critique of true crime. Even as you pick apart the genre tropes and point to specific shows or movies as examples, it’s clear from the narration that you’ve enjoyed many of these yourself. How did you decide how overtly critical to be?

CS: The realization I had while making the film was that the critique that was valuable to me actually relied on acknowledging an affection for the genre. At various points in the edit, there were sequences where I was talking about true crime shows or films that I didn’t really like, that I maybe had seen purely for research, not for pleasure, and that were maybe on the more low-rent, sensational end of true crime. They have plenty of flaws that were worthy of criticism, but those criticisms just felt like they lacked something essential, which was an understanding of how you could still feel engaged and still feel drawn to the genre despite those shortcomings.

In the end, the ones that stayed in the edit were those that, while I might have quite significant ethical objections to them, are also all shows and films that I have watched, in some cases more than once, for pleasure. For the most part, they're kind of the most “prestige” works that the genre has had to offer for the last decade or two. That felt important to me if I was going to understand the feeling I had arrived at about true crime as one of contradiction. The unease was sort of meaningless if it didn’t come coupled with this pull towards the genre.

SM: When you started working on the original project, true crime was huge, and it’s still huge now that you have a completely different film coming out. It’s a never-ending stream for consumers, but it also seems like it’s shaping non-fiction film and the industry at large. It feels almost unavoidable to be working in unscripted film or television to not work on true crime right now. How do you feel about the genre and its place in the industry at this stage?

CS: The thing that’s most striking to me is just how similar it is to all the stuff I was watching two years ago while I was working on this film, and all the stuff I was watching five years ago while I was trying to make my own true crime documentary. I keep thinking the train is going to come off the tracks, but it seems to just keep on going. That points towards one of the genre’s strengths—at least as far as the industry sees things—which is that it's infinitely replicable.

There’s always another crime and the storytelling molds we fit those crimes into are solid and predictable enough that you can pretty quickly shape any story into a 6-episode mini series or a 90-minute feature film, or whatever format is in vogue at that moment. I went into this assuming that true crime had a life cycle, but I don’t really know what to think now.

SM: I actually think people are very tired of it, but that doesn’t necessarily preclude us from watching it.

CS: I don’t put that on the audience either. I don’t think there's any reason to think that people are clamoring for more of this stuff. Like we’ve both said, most of the true crime I’ve seen has been somewhat passive. I get home at the end of the day, I put a streaming service on, and it’s the first thing that comes up so I watch it. It’s not exactly appointment viewing for the most part. It’s just there. It may be “second screen content,” to use the horrendous buzzphrase, but I think the real driving force, inevitably, is that people like me keep making it.

SM: Well, this project is interesting because it arose out of what possibly could have been “second screen content,” but it instead demands your attention in a more rigorous way.

CS: Here’s hoping. And to be fair, if it ends up being second screen content, there’s certainly all kinds of weird Zodiac Killer forum threads that people could land on to find out more about the story as they watch, so maybe it can be an interactive experience.

Zodiac Killer Project screens November 21-27 at IFC Center. Director Charlie Shackleton will be in attendance for select screenings.