When David Friedman, initially approached to be interviewed for a short film about children’s birthday party entertainers in New York City, opened up about a sexual abuse case involving his father and his younger brother, director Andrew Jarecki knew he’d stumbled upon the kind of story filmmakers wait their entire lives for. The resulting film, 2003’s Capturing the Friedmans, is a simultaneously poignant and grotesque depiction of a family and a community torn apart by unspeakable acts.

In the late 1980s, Arnold Friedman, a Long Island school teacher, and his 19-year-old son, Jesse, pled guilty to molesting students in an after-school computer class. Through talking-head interviews, a portrait emerges of two men seemingly railroaded by overzealous investigators who intimidated young boys into detailing acts of sexual violence that never occurred — shades of the McMartin preschool trial. But that image shifts as viewers learn that Arnold had revealed to others, including his wife, a therapist, and a journalist, that he had on different occasions assaulted other victims, including his younger brother.

True crime filmmaking has at times illuminated and combated systemic injustice: Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line led to the release of the wrongfully imprisoned Randall Adams, while Jarecki’s 2015 series The Jinx resulted in Robert Durst’s being charged for the murder of Susan Berman. But there are no cut-and-dried takeaways with Capturing the Friedmans — Jarecki revels in cultivating ambiguity, perhaps to a fault. In the years following the film’s release, some have accused the director of playing fast and loose with the facts to tell a more enigmatic, and more fascinating, story. He omits mention of a codefendant, Ross Goldstein, who pled guilty and testified that he and Arnold and Jesse Friedman had assaulted students, and several former students have said that their accounts of sexual abuse by the Friedmans were neither coerced nor the result of hypnosis. While tackling these issues head-on would have strengthened the film, for all its flaws it’s still a mesmerizing work, and its message that sometimes there are no pat conclusions is a powerful one.

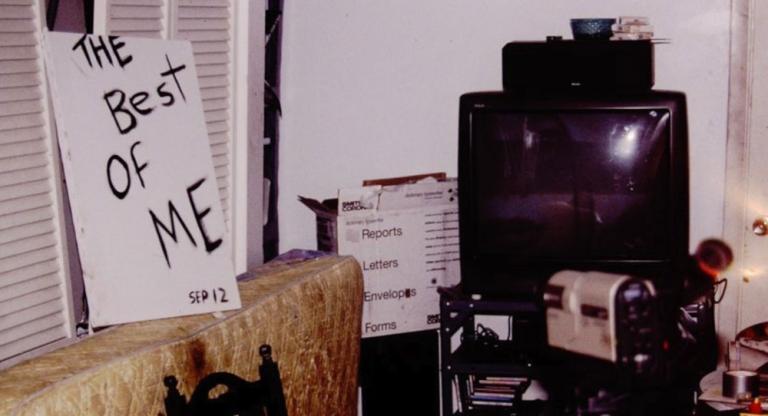

If the film has an agenda, it’s the argument that Jesse Friedman is, if not definitively innocent, nevertheless also a victim, haunted by the sins of a father whose childhood was filled with horrors. The director’s vivid, startlingly intimate portrayal of a devastated family has the feeling of a Greek tragedy. Skillful interviews and the use of home movie footage give the subjects depth; the Friedmans chronicled their lives with a fervor more typical of the Instagram generation, filming agonizing fights as the schism between the Friedman sons and Elaine widened to a chasm. More than seamy details about the abuse and the trial, it’s this painfully honest depiction of a family slowly falling apart that will linger with viewers.