After the Curfew opens on footsteps. A flashlight sweeps the wet ground, then finds a sign announcing the titular restriction. A bell tolls the hour of its effect, and an armed patrol appears to enforce its terms, giving chase through the streets and alleys of Bandung, the capital of West Java.

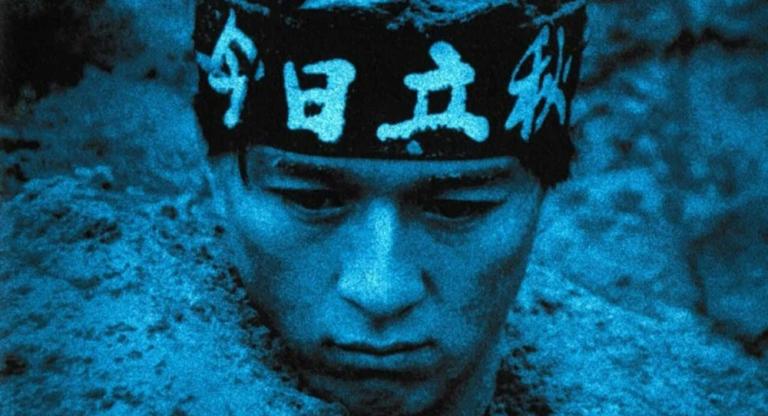

In the first minutes, fleeting glimpses are all we catch of Iskander (A. N. Alcaff), a soldier returning home after five years fighting in Indonesia's War of Independence from the Dutch (a war in which the director, Usmar Ismail, had served as a major, the resulting republic not even five years old at the time of the film's release). We finally find him in the garden, a flower in hand for his fiancée, Norma (Netty Herawaty). Her family has been sitting around the kitchen table, fretting over his prospects: “Idleness could destroy him.”

At the outset, Iskander is the beneficiary of provisional kindnesses, the pittance afforded to a revolutionary of his station. Norma's father finds him a government job, and his new boss commends him for his service. Once inside the stuffy workroom of the bureau, however, he is subjected to the suspicion and contempt of his fellows (“Aren’t we freedom fighters too?”) The clamor of office machinery works at his nerves until his hand slips, spilling an inkwell. He is confronted and insulted, panics and returns the incivility with force.

The rest of the film unfolds over the course of a day and a night, its characters meeting and parting across a repeating series of interiors. The story of Iskander's dismissal from his post is recounted several times to his former comrades in arms, who have been back a little longer and situated themselves in various shades of service to and exploitation of the new postcolonial order. The pace slows to languor in the home of Puja (Bambang Hermanto), now living as a gambler and a pimp with Laila (Dhalia), a sex worker who spends her off-hours clipping pictures out of American magazines, affixing fantasies to the woven bamboo walls. Amid disillusion and betrayal, Iskander finds himself drawn to her bold desperation, untouched by shame.

After the Curfew was restored and re-released in 2012 on the recommendation of J. B. Kristanto, the Indonesian film journalist and historian. In a Criterion featurette, he outlines the context of a developing national film culture in which Ismail's social realism was a striking exception. The film was a prestige production, a collaboration between two rival studios, Perfini and Persari. It was intended to appear at the inaugural Asia Film Festival in Tokyo but was withheld by the state in protest of unpaid debts from the Japanese occupation.

Iskander’s tragedy is born of the corruption of an ideal, in which a soldier of the revolution can become the henchman to a despot. His features, once set with determination, gradually melt into a lopsided grimace. For some, the world has changed entirely, while others skirt the inconveniences of martial law, singing parlor songs at all-night parties.