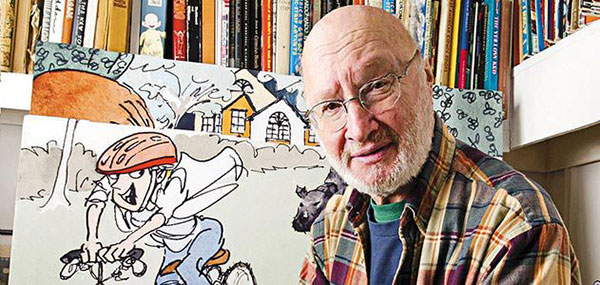

To my mind, there are few screenwriters with as mesmerizing a career as Jules Feiffer, the Village Voice satirist and cartoonist whose work manifested into just three direct-to-screen pictures, one play adaptation, and an array of unproduced screenplays—one of which was plucked from the archives last year. One aspect of my affection for Feiffer's work comes from the way I was introduced to him: as a wide-eyed fourth grader assigned his 1995 children's novel A Barrel of Laughs, A Veil of Tears for school, immediately recognizing his cartoon-style as the cover of my heavily-used copy of The Phantom Tollbooth . Most grade-school assignments did not linger—I can't remember a lick of Where the Red Fern Grows —but Feiffer stuck with me. His work has the feel of a boyish whirl meets the delirious dysfunctions of the world, a sensibility I would later find in authors like Nathanael West (who I learned was an influence) or Kenneth Patchen's novels, and almost nowhere else.

In college I sought out Little Murders, Alan Arkin's directorial debut, adapted by Feiffer from his first play. Elliott Gould is a photographer resigned to the violences of the world, having the shit kicked out of him in the opening scene with little interest in fighting back. He falls in love, more-or-less against his will, plunging him into a comedy-of-manners with a backdrop of arbitrary slayings and the erosion of any meaningful authority. Written in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, it came together as Feiffer had his own brush with violence, having been sought out for advice by subsequent synagogue shooter Richard Wishnetsky as he was fine-tuning the script. The play premiered to little fanfare, gaining traction two years later with a zeitgeist revival amidst the climate of student demonstrations and the Vietnam war.

The film screens today as part of Film Forum's Far-Out in the '70s , and, as is the case with various other films in the program, it exudes the distinct aura of a deep cultural déja vu. It only makes sense: we have hardly dislodged from the logic of Watergate, wars abroad, or Norman Lear sitcoms. One-time Nixon staffer Roger Stone is flashing the V-sign as he pleads not-guilty; Elaine May is back at the Golden Theater alongside Michael Cera; Feiffer's Carnal Knowledge feels just as much a comment on the contemporary gender politics of Internet pick-up artists and "soft boys" as it was a reflection of the early stirrings of the women's liberation movement.

Ahead of Little Murders'screening, I spoke to Jules Feiffer by phone. We discuss his screenwriting career, his encounters with certain canonical arthouse filmmakers, and the stasis that undergirds American life. He is no stranger to historical cycles—still active as a cartoonist, his most recent graphic novel The Ghost Script is fittingly about the ghosts that haunt Hollywood and our collective inability to break culture's perilous repetitions. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

TM: To start, I wanted to ask you about Elaine May and Mike Nichols' comedy, because a large part of the current Film Forum '70s comedy program is honoring Elaine May's work. Would you talk about why you connected with them so much?

JF: I began my Voice strip in 1956, and around that time Mike and Elaine were in the early stages of the Compass Players in Chicago. Without anybody knowing what anybody else was working at it, there was a whole school of underground comedy that was commenting on the politics and sexual mores and cultural give-and-take of post-Joe McCarthy, post-Dwight Eisenhower America. Because there was very little happening at the time in the respectable forums of opinion that was a meaningful critique of what was going on at the time, it began happening in underground nightclubs and cabarets and in my cartoon at the Village Voice. The first surface manifestation of it that I know of was Mort Sahl in San Francisco at the Hungry I, and then it built up from there. All of us were doing it, without knowing each other or being aware of each other. We were commenting in a satirical way on things that nobody else was commenting on.

TM: How did you encounter May and Nichols?

JF: I first became aware of Mike and Elaine when I saw them on a CBS show called Omnibus, which was an hour and a half evening show once a week that Alistair Cooke, the British commentator, hosted. I was working in New Rochelle for Terrytoons and just in my early time at the Voice, which wasn't paying me. So I had to get a job, and I got a job in animation. I came home, heated up something for dinner—some frozen food—sat in front of the TV, and Alistair Cooke introduced these new comedians, Mike Nichols and Elaine May. And what I saw this extraordinary couple do… Their first piece was about teenagers, a couple in a car. The next piece was about a mother and her son, her guilt tripping him. And I thought I was seeing my work onscreen by these performers, except they were better than I was! I mean, they got past what I was doing. I was just so enthralled. I worked hard not to laugh because I might miss a line. Then I found out they were going to be at the Village Vanguard, New York, so I went down to see them. We became friends. I discovered they had been reading me in the Voice all along. They were aware of me and I was aware of them. But that's how that relationship began.

TM: I read that you had been in touch with Stanley Kubrick before Terry Southern was been roped into Dr. Strangelove

JF: Well Stanley, another Bronx boy like me, loved my dancer [cartoons for the Village Voice ] and talked to me about doing a film centering on her. I forget whether I was out in California at the time or New York at the time. Now, I loved Kubrick's early works that I saw: Fear and Desire and some others, the early stuff. I thought he'd be great to work with. But unlike Nichols, who I would work with later, it became clear with Kubrick that he was going to control everything, that it wouldn't be a collaboration. I wouldn't be working with him, I'd be working for him. And while I was a great admirer, that was not the way I saw my role—that I was not going to write a script with my dancer and turn it over to him to make it his dancer. So on that occasion, and also with Dr. Strangelove, which he had offered me, I thought I'd love to do something with Kubrick, but I don't want to be 'the help.' But that's exactly what I would have been. So in each case I walked away.

Now with Strangelove, the vision that Terry Southern and Kubrick came up with, was so far afield from anything I would have done, and so much better than anything I would have come up with. I mean, they did the MAD Magazine version, which I never would have done. I think he made one of the great films of our time.

TM: The issue of control is interesting because it seems like it's a problem with screenwriting more than playwriting—and certainly more than cartoons, where you have total control. With studio films, you finish something, you give it to a director, and then you lose it.

JF: Yes. Unless I was willing, as I was at certain times, to hack for the money. I wrote a number of screenplays over a number of years when I had a young family and I simply wasn't making enough by other means. I would devote three or four months of the year to writing a screenplay for a Hollywood director or producer, knowing it would never be made. I'd ask them for all the money in the first draft, because I knew they would never be. At the time, my agent was strongly opposed to this. "But I'm making you ten million dollars on the first day of principal photography!" And I'd say, "It's never going to come to that! Give me fifty cents on the first day of principle photography, all the money for the first draft." And that's what we did. And that's how I made a living for four or five years. From films that never got made.

This is the line I came up with about what Hollywood thought about my work is: they love the idea of me, but they hate the fact of me. When I did this work for other people, they thought it was terrific, when I did it for them, they didn't want to touch it.

TM: Why do you think that is?

JF: Because I was, to them, controversial. I stated things a little too boldly of them, but that was the way I thought, that was the way I viewed things. I wrote what I thought and that hasn't changed to this day. Nichols had the first screening in Hollywood for the Screen Directors Guild of Carnal Knowledge. After the film, we were standing in the usual reception line with drinks in our hand. A procession of the great directors and Hollywood types would move past us. I don't remember the names, but it was, you know, William Wyler and a lot of very famous, reputable, and very good directors. One would walk by and say, "It was like open heart surgery." Another would say something else like that that, and another, and another. I leaned over to Mike after the third or fourth and whispered to him, "We're dead." And we were. It came out that year. It didn't garner any nominations except for Ann-Margret, who deserved one—but so did Nicholson and so did Nichols. And I wasn't nominated for screenplay. So Hollywood shunned that movie, except for one of its own, Ann-Margret.

TM: I read an interview you did in the '80s where you mentioned that you had intended Carnal Knowledge to be very specifically about your generation. You felt like it was going to end up dated. But interestingly—watching it now, it feels prescient.

JF: Well, in both cases, Little Murders and Carnal Knowledge, they were both written as cautionary satires and I thought that, God willing, they would be out of date. Well, God willing, they are as timely now as they were back then—which is perhaps a say something less about the effect of the art than about how American society does not change, no matter what it does. The language may change and the cover stories may change, but the dislike of the heterosexual male for women remains as exactly in place as it was when I wrote Carnal Knowledge, and long before Carnal Knowledge. The scenes of underground disruption, chaos and anarchy, under the rules of a formal society are if anything more in place today than when I wrote Little Murders. The films can't date because the society has stayed in the same place, just with a different cover story, and that's unfortunate. But it's good news for my art.

TM: With Little Murders, I hear that you eventually didn't have much to do with the movie, that you felt shut out.

JF: It was Arkin's first directing job in movies. He had directed Little Murders at Circle in the Square on Bleecker Street, and the White House Murder Case at the same theater, and done a brilliant job. Alan was very iffy about my presence and my opinions, and he didn't see very happy to have me around, so I hung around some but I learned to keep my mouth shut. I let him do what he was going to do and when he asked me to rewrite stuff, I did that. But when I offered opinions and judgments, they were seldom if ever acted upon. So I had very little to do with the with that film. When I first saw the final cut of it, I was less than happy with it. And it's amazed me over the years how the film has improved and gotten better and better. I may have been mistaken. I think it's now a very good piece of work indeed.

TM: When Elliot Gould was first trying to produce it, he talked to Jean-Luc Godard?

JF: Oh yes. And I met with Godard.

TM: What was that like?

JF: It was awful. It was awful. And I was a fan of Godard. I thought there was a lot in his film Weekend that I was hoping he would bring to a Little Murders. There's long traffic scene in Weekend that I thought was exactly in the spirit, and I knew Godard had been referred to me in one of his films and followed me because I was being published in France at the time, in Paris. But it was clear to me that this was just a money gig for him. He was going to raise money on Little Murders to do his own films and he didn't give a shit about this piece of work. It was not a good meeting at all and I didn't like him at all. So that was that. I thought from the beginning he was treating me and the rest of us with utter disrespect.

TM: I just watched I Want to Go Home.

JF: Resnais, unlike Godard, was the most charming, affable man—his English was terrible and I had no French, but he was so outgoing, and clearly such an admirer of mine. He was a very handsome man and he had a kind of sweetness about him. Which was counter to what you would see on film, but that's way he was personally. I started talking to him, and--so I had written a second novel called Ackroyd, which was a complete failure, which he loved. He said that was why he came to me to do this film. Ackroyd, this total flop of a book, was what he so admired. We talked about something I might do and I basically came up with the idea of I Want To Go Home.

First of all, it was going to be a has-been comedian in Paris. But Alain said, quite correctly, "Oh no, people will think it is Jerry Lewis," which is who I had in mind. He didn't want to do that. So I turned him into a has-been cartoonist, which was much closer my own field anyway. That Resnais liked, and I wrote the script, talking back and forth [with him]. We would be in New York, and I think I was in Paris a few times, and we'd go over stuff. It was very funny because his English was very fractured and my French was non-existent. How we communicated with each other, I don't know. But there was such good will on both our parts. We liked each other. Even when meetings were more or less incomprehensible, there was an aura of pleasure connected to all of it.

For me, I thought I was winning some great scam on Renais, because what I wanted to do, most of all—the reason I want to do this film—was to be able to take my family to Paris so we would all be in Paris for two or three months. What could be better than that? And then when I finished the script and we were casting it—and I'll tell you about that in a moment—he told me he didn't want me on the shoot. He said, and this is direct quote, "Oh no, the actors will not know who to listen to, to you or to me." I thought that was so ridiculous, that a screenwriter might have precedence over the director. In any case, he clearly didn't want me in the neighborhood. So I was not going to be in Paris, and my grand scheme was not working out at all. The best I could do is get my 20-year-old daughter Kate a job as an assistant on the film helping out the leading star, Adolph Green, who Resnais had wanted to cast from the very beginning.

One of the charming parts of earlier on in the film was he had asked me to deal with Adolph, who was a friend of mine, and tell him that Resnais was shy of approaching him. So that was my job. That's what I did at a dinner at the Russian Tea Room. I had sent Adolph the script asking him what he thought of it without telling him anything about the part, and he and his wife, Phyllis, we all had dinner at the Russian Tea Room. We talked for a while and then I said, "Look, everything I've told you, it was bullshit. I brought you here under false circumstances. Renais wants you to start the film as Joey Wheelman." I still remember Phyllis Newman screamed. She put her hands up to her face, she went, "AHHH!" Adolph just blinked and looked stunned. And then we celebrated for the rest of the evening because there was no question he was going to do it. He couldn't believe that they wanted him. It was one of my fondest memories connected to that production.

TM: I understand that Renais was very interested in American comics?

JF: Resnais was a great fan of comics, as you just said. There was something about Mandrake the Magician that Fellini loved and Resnais loved. I don't know what it was. When I met Fellini for the first time, he just wanted to talk about Mandrake, and if I knew Lee Falk who created Mandrake. I did know Lee Falk. So I was with these great directors talking about American comic strips.

TM: I take it this is partially where I Want To Go Home comes out of, the bizarre interaction between European intellectual types and their fixation on American culture. Trying to bridge that gap.

JF: Well, again, it's like how Jerry Lewis, who was only thought of as Jerry Lewis the slapstick comedian here, was this cultural figure over in Europe. And so it was with some of our comic strips, that had become iconic to Europeans, such as Mandrake the Magician. Certainly none of the American strips that I, as a young man or as an adult, loved and took seriously and influenced me— like Will Eisner's The Spirit or Milton Caniff's Terry & The Pirates—the Europeans didn't give a crap about any of those. They were drawn to other things, some of which I thought were okay, some of which I didn't get at all.

TM: Let's talk about Popeye quickly...

JF: Sure. I could talk about Popeye longly. Richard Sylbert was the production designer on Carnal Knowledge. We were good friends. When Bob Evans originally approached Sylbert to be the producer of Popeye and asked them who could write it, he said "Feiffer is the only one who can make these characters real." So Evans called me up—I think I might've met him once years or you know, briefly in Hollywood, but I did, I didn't know him—and said he wanted to write Popeye and would I? I said, it depends on which Popeye you mean. If you want the Max Fleischer Popeye, the animated Popeyes—I hated them and I wasn't interested in it. If you want to do the E.C. Segar Popeye—Segar was the original author of Popeye in the newspapers. I said, I'm your guy because I think they're works of genius. He said, I want to do whatever Popeye you want to do. So we were in business. And from that time on, everything and anything I had to do with Evans was terrific. I mean, he was totally supportive from the beginning until the end, and through all the difficulties I had on the film, that included Dustin Hoffman and other things. He was in my corner all the way to the point where he made some stupid decisions because they were my decisions and I was all wrong.

I had vetoed as a director Louis Malle. Louis Malle wanted to do it. And I had forgotten Atlantic City and how much I loved it now and how perfect it was, and I said, no, you need an American. Which was stupid. If Louis Malle had done it, it would've been a different Popeye, but it would've been a much better film—although I think there was a lot in Altman's film that was wonderful. Evans in this case took me seriously when he shouldn't have. And it was one of my many serious career fuck ups.

Then when it was a choice between Jerry Lewis and Altman... What was I going to do? Altman was a friend of mine—we used to have dinner a lot of in New York at Elaine's—but I knew that he would trash the script, because he trashed every script he worked with. I knew he was a genius, so he would do something interesting, and I knew that he would make these cartoon characters onscreen and seem very real, which in fact he did do. So I was just hoping that somehow we'd get away with it. And in some ways we did it, in many ways we didn't.

TM: So how would you summarize your screenwriting career? I mean, you were only partly understood by Hollywood. What do you make of the work you did on-screen?

JF: I never thought of myself as a screenwriter. I thought of myself as a playwright, but when I wrote movies... I'll tell you what, let me answer it this way. It seems to me that the best screenwriting I've done, outside of Carnal Knowledge, is the trilogy of graphic novels that I've already completed last year called Kill My Mother. I conceived of them as I would movies on paper. I approached them from the script to the layouts as movies on paper and in which I played every role. I was all the actors and cast all the actors. Not only was I the screenwriter, but I was the director who threw out the script of the screenwriter and rewrote lines as I was doing the finished page. More and more as I did the trilogy, it became more cinematic to me and more movies on paper. If you don't know them, I would familiarize myself with them. Anyhow, it's the work in recent years that I'm more proud of than anything else I've done in many, many, many years.