Perhaps my favorite facet of West Coast lo-fi nihilist Jon Moritsugu’s domestic psychodrama Terminal USA (1993) is that it was funded and broadcast by PBS, specifically by it’s newfangled offshoot, the Independent Television Service, which was devised with the intention of producing subversive work from up-and-coming filmmakers. (Todd Haynes’ Dottie Gets Spanked was part of the same series as Terminal USA, entitled “TV Families.”) ITVS’s offerings immediately became the target of conservative critics aghast at the productions being funded with taxpayer dollars. (“It’s going to be a long year,” ITVS’s James T. Yee bemoans in a New York Times piece about the ensuing fallout.)

For Moritsugu’s satire — now playing as part of Sentient.Art.Film’s “My Sight is Lined with Visions: 1990s Asian American Film & Video” — the context is perfect; the film comes like a wolf in the clothing of the exact type of film it’s tearing to shreds. As critic Girish Shambu writes in an essay that accompanies the stream, the Center for Asian American Media, which came out of PBS’s push for more diverse programming in the 1970s, allowed Asian American filmmakers to create new work on one condition: that it fit into a mold of “positive” — assimilated, upwardly-mobile — representation. This inevitably resulted in work that was, in the words of critic Daryl Chin in Making Asian American Film and Video, “noble and uplifting and boring as hell.”

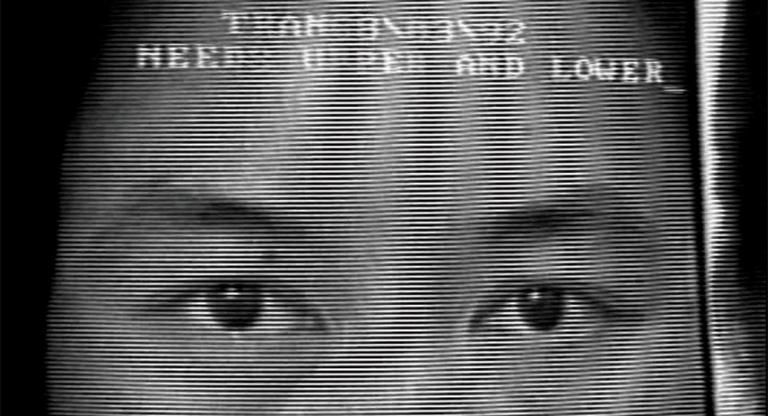

Terminal USA traffics in the syntax of American sitcoms and suburban melodramas like Nicholas Ray’s Bigger than Life. The camera glides through an ornate, colorfully-lit soundstage dolled up to look like the modest home of a Japanese-American family on the brink: one son, Marvin (played by Moritsugu), is the consummate student harboring a closeted insatiable lust for skinhead boys; the other, Katzumi (also Moritsugu), is a drug-dealing black sheep who, together with his layabout, maybe extraterrestrial girlfriend Eightball (who objectively rules and is played by Amy Davis), owes said skinheads a lot of money; and the daughter, Holly (Jenny Woo), is a cheerleader juggling an unexpected pregnancy and a missing sex tape. The revelation of each of these circumstances puts increasing pressure on the just-fired patriarch (Ken Narasaki), whose Jokerfication is the crux of the film and climaxes in a blood-soaked slumber party.

The highlighting of the unnerving and the otherworldly in the American immigrant (not to mention queer) experience positions Moritsugu alongside his West Coast punk contemporaries Roddy Bogawa and Gregg Araki; sure enough, Terminal USA was produced by New Queer Cinema mainstay Andrea Sperling, who was also responsible for much of Araki’s filmography. Also included alongside Terminal USA in Sentient.Art.Film’s series is Mortisugu’s Mommy Mommy Where’s My Brain (1986), an anti-academic and deliriously noisy short that furthers Moritsugu’s notion of tearing down the genres that he utilizes.