“Ahead-of-its-time” is an overused phrase that usually fails to deliver on its intrigue. Write-ups of Jonathan Caouette’s 2003 feature Tarnation describe it as such so often that it feels dismissive (the Criterion Channel, where it’s recently made its streaming debut, is the latest to wave off further analysis with the trite descriptor). Still, it’s preferable to “narcissistic,” the adjective that poxed nearly every contemporaneous write-up of Tarnation.

Caouette’s documentary compiles decades of home videos, photographs, audio recordings, and movie clips from formative media — everything from Rosemary’s Baby to PBS’s Zoom — to create a self-portrait-cum-family-reckoning that’s detailed and precise, yet impressionistic, like a Chuck Close painting. Pared-down, on-screen text lays out the specifics of the story: Jonathan’s mother, Renee, was 12 when she fell from a roof and was paralyzed. Believing it all in her head, her parents forced her to undergo electroshock therapy, which left her permanently stricken.

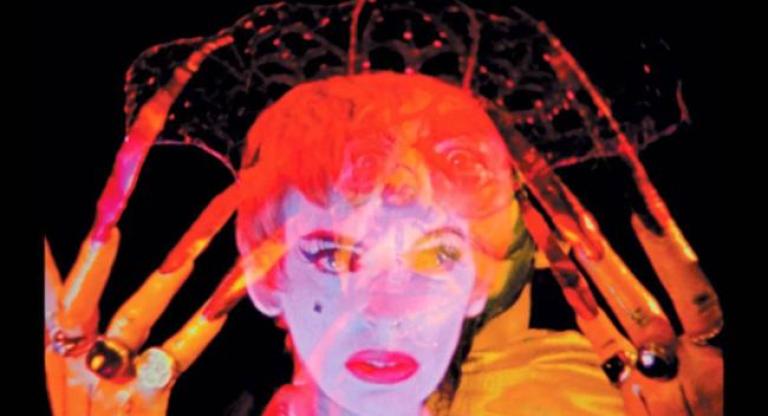

Jonathan was born and taken into foster-care when he was a toddler. He returned home as a preteen and began to obsessively document his life — real and imagined. As a boy, he performs a monologue, taking on the role of an abused wife who kills her husband. He coaxes his grandmother to mug and yell “Where’s my teeth?” He recounts smoking a PCP-laced joint when he was a preteen over footage of a bloody staged suicide: an incident that triggered the onset of depersonalization disorder. The camera, we can surmise, provided a sense of camaraderie for Caouette, who often felt as though he, too, was experiencing reality secondhand.

Early reviews of Tarnation from Sundance and Cannes were fawning. But as the filmbegan to trickle into wider release, the discourse darkened. Ostensibly, the concerns were ethical. Critics cited issues of consent and several scenes showing Caouette’s family in various states of confusion. In one of the film’s most controversial sequences, Renee dances ecstatically with a pumpkin. Nevermind that Gummo — which featured mentally impaired actors unrelated to the filmmaker playing prostitutes and singing Jesus ditties — was released six years prior. Harmony Korine’s contributions notwithstanding, the question of consent in countless documentaries focused on war-torn countries and the world’s most impoverished regions is usually, curiously, absent.

Today, these indictments read alternately as homophobic and hoary. In 2005, The Atlantic demanded to know why Caouette didn't include material about his experience growing up gay in Texas, or his relationship with a woman who gave birth to his son. In a gentler take that nonetheless ran under the headline "Enter Narci-Cinema," A.O. Scott described with wonder the ability of handheld cameras to swivel and face their operator. He coined the term "moicumentary" to describe Tarnation.

If there’s any doubt that that elder generations still hate it when non-cis-white-hetero youth try to speak on their own behalf, look no further than the treatment of the survivors of the 2018 Parkland school shooting. The pushback against Tarnation assumed a moralizing tone to obscure what now seems obvious: that rather than being outraged that Caouette shared a story that wasn’t his to tell, he told one that was.