Anthony Ramos was among the earliest artists to use video as a tool for mass-media critiques and cultural documentation, producing an eclectic array of video works between 1971 and 1989 that range from durational performances to experimental travelogs. A significant but under-recognized figure in both East and West Coast art scenes, Ramos was a peer and friend of Nam June Paik, Juan Downey, and others. His videos are indelible interventions into the canon of early video and performance art, though many of them are rarely screened. The artist makes a rare trip this week to New York for a career-spanning series of programs.

Ramos had several formative encounters while he was a student at Southern Illinois University in the 1960s: Buckminster Fuller was on faculty, and Allan Kaprow staged a number of happenings there and became a life-long friend. Ramos participated in these performances, and embraced their situational ephemerality and their blurring of art and life. Later, while serving an 18-month sentence for conscientiously objecting to the Vietnam War draft, he considered the prison stint a kind of happening.

Kaprow kept in touch with Ramos while he was in prison and advocated for his release. His best support came in the form of an invitation to continue his art studies at the newly opened California Institute of the Arts. It was there that Ramos was introduced to video, and he used it to record and disseminate his intentionally difficult performances, mounting a resistance to the hegemony of white, consumerist America as seen on the boob tube.

This conversation, edited for flow and clarity, homes in on his early video-performances and friendship with Kaprow.

Rebecca Cleman: Tony, you’ve previously described your arrival to California after your release from prison. I believe Allan Kaprow picked you up at the airport in a convertible? Can you set the scene a bit?

Anthony Ramos: It was New Year's 1971, straight from solitary confinement, and [we] must have been [driving] a Mustang convertible in sunny Southern California. We drove to [Kaprow’s] incredible house in Pasadena. I fell asleep that first night, and they had an earthquake—the ’71 earthquake! I was just so exhausted, I slept through it. That's how I started at CalArts, being Allan's graduate student. [His class] was all about having to make happenings—you know, make things happen. We had these video machines [Sony Portapaks –Ed.]. In effect, we started out doing happenings and making documents of what we were doing. And that soon led to Hey, this is a magic box in itself. Rather than just using it to record what we're doing, we can make content. The context was— Well, it was [the] ’70s. We were all involved with Bucky Fuller and Marshall McLuhan and all of that kind of stuff. And along with Kaprow, Marcel Duchamp was a big part of our education.

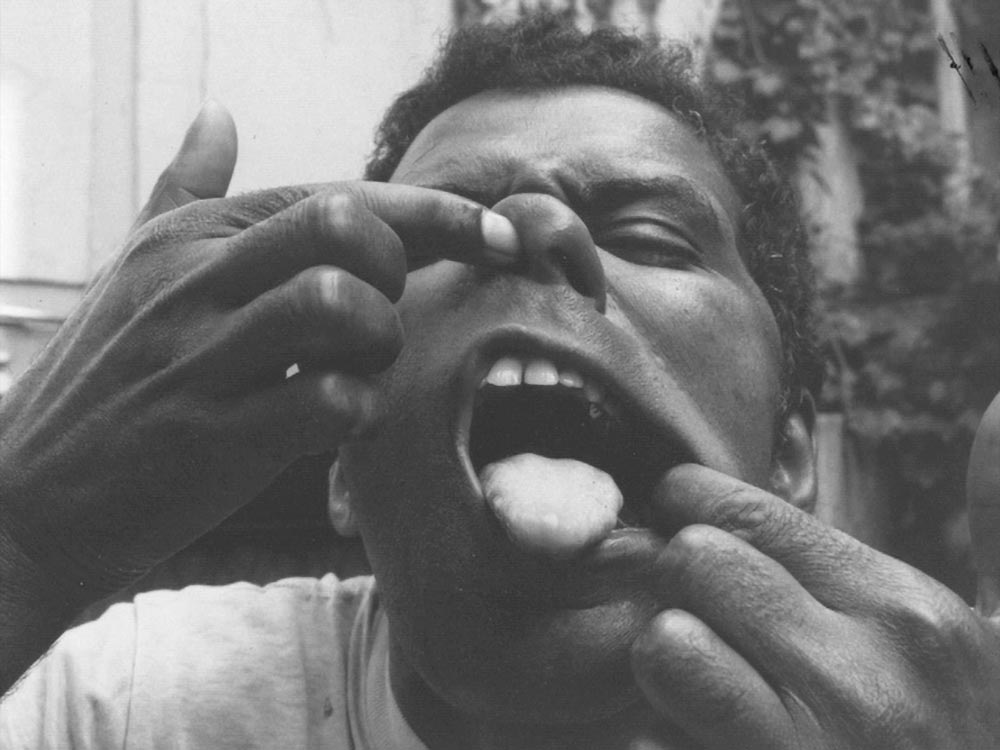

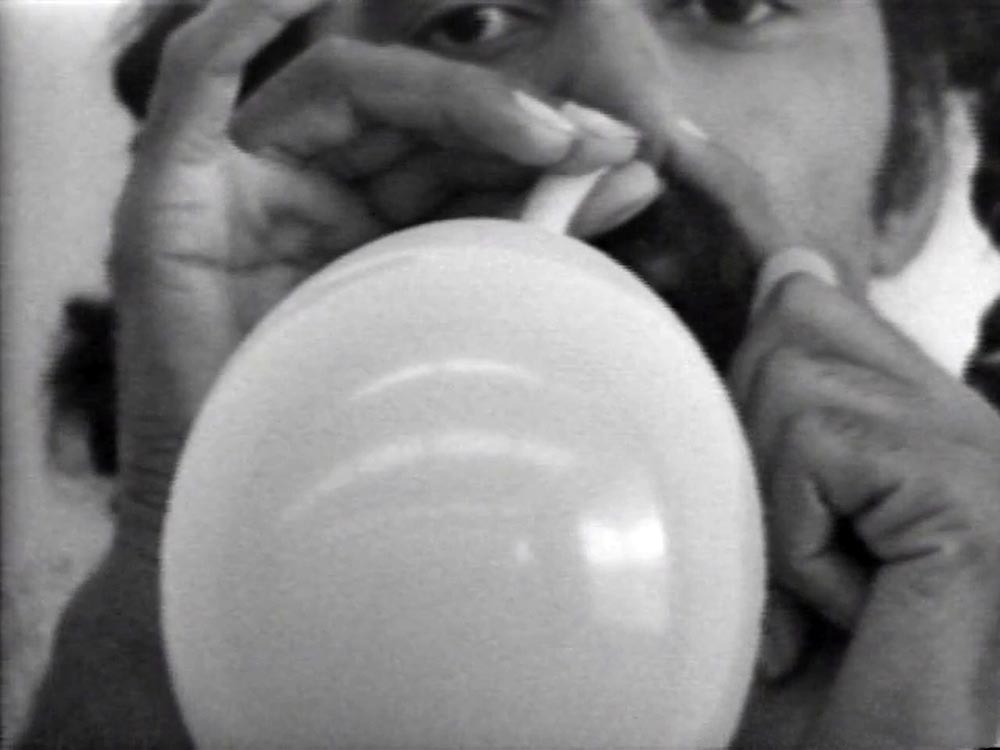

RC: In one of your earliest videos, Balloon Nose Blow-Up (1971-72), your face is tightly framed as you stare directly into the camera, blowing up a “Happy Birthday” balloon with one nostril until it blows up in your—and the viewer’s—face. It’s pretty uncomfortable.

AR: That was exactly the idea! Tak[ing] such a simple gesture and mak[ing] people very, very, very uncomfortable. That was exactly the idea. [Those] were uncomfortable times. These are still uncomfortable times!

RC: It also seems to be a deliberate unseating of the televisual “talking head”—in those days, almost always a stone-faced white man in a suit. You seem to be interested in disrupting, or literally blowing up, this particular dynamic, between the passive viewer and the network authority figure. I’m thinking of course about how dominant television was at the time. It was the main communication platform—the conduit through which most news and entertainment was delivered into the home.

AR: It was like radio [had been] for Hitler and Mussolini and Roosevelt. The television took over from that [and everybody was] really glued to the TV—for the information, for their entertainment, etc. But there were only three [networks]: NBC, ABC, CBS. Yeah, that was the news. You know, and then you had Howdy Doody, and all of that kind of stuff. You know, the Vietnam War was going on. The Civil Rights Movement was still going on. Black Panthers, women's rights, gay rights: it was all going on. And we had this machine that could address those issues without the middleman of ABC, NBC, CBS. And although our audience was very, very limited, it was out there.

RC: The 1960s is a decade that really saw the so-called apotheosis of television—a lot of major media events, good and bad, happened that decade. Presidential debates, JFK’s funeral, which was broadcast live on video, the Vietnam War, street protests, the moon landing of 1969. I think you were in prison during the moon landing? That was the largest television audience yet.

AR: Yes, I missed it. But I did get to see 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968]. It was the only movie that I went to go see in jail.

RC: Right. So out of jail, you arrive into the warm embrace of sunny Los Angeles. And you’re part of the inaugural class at CalArts. You’re there with Nam June Paik, John Baldessari, so many other artists. Who all was there? What were your impressions of L.A.?

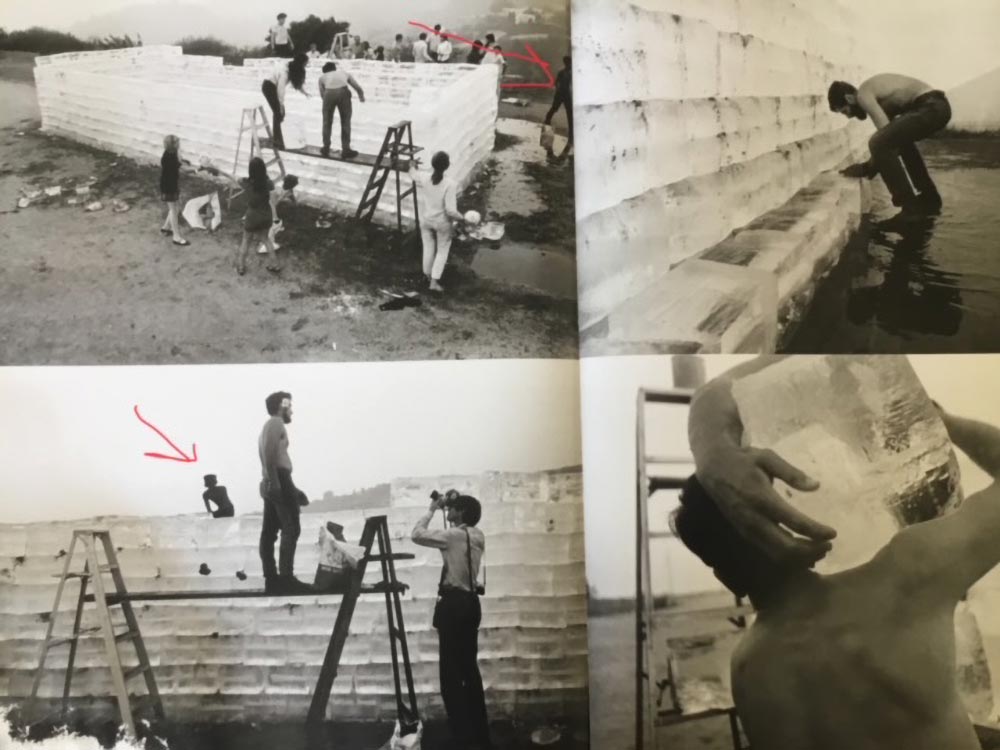

AR: I had been in L.A. before, because I had gone off to do this happening with with Allan [Fluids (1968)]. It was like 110 degrees, and he built all these incredible ice structures all over the city.

But CalArts . . . It was really the Bauhaus of its time. Let's see, who was there that I knew personally? John Baldessari. Ross Bleckner. Barbara Bloom. Sheila de Bretteville! Judy Chicago was there. Simone Forti, there was a fabulous human being. Eric Fischl. Charlemagne Palestine was great, he was really something. Jack Goldstein. Stephan von Huene. Alison Knowles. Suzanne Lacy . . . I mean it was a who’s who. And those were just the ones I knew! There was Greg Edwards, who was Mel Edwards’s brother, who was a great artist. And Joe Ray, one of the guys in Plastic Bag Tie-Up, was an absolutely fantastic artist.

RC: And Lowell Darling as well.

AR: Lowell, definitely. But Lowell was not CalArts. He was part of the art movement in Los Angeles. He’s another great unsung hero, Lowell Darling, [who] sew[ed] the San Andreas Fault together. He had an amazing sense of humor. He ran for governor and got [more than 60 thousand] votes!

RC: It’s great to hear about your connection to Darling because what you’re admiring in his art is what I’d observe in yours too: your humor, and how you use that to stage powerful and incisive critiques that undermine governmental, or commercial, power structures.

AR: There was a lot of that going on. Like Abbie Hoffman going into Wall Street and throwing money onto the floor. Now there's somebody that understood media.

RC: Was Hoffman an influence on you?

AR: Not necessarily, but he was in the air. You know, he's like the Black Panthers, like Angela Davis. They were major parts of the media presentation of the time, but they weren't “official” people. They were people fighting the power, if you will.

RC: You made a series of amazing performance videos at CalArts, including State of the Union (1974), another obvious televisual scenario, and Watermelon Heaven (1972).

AR: The whole idea [with Watermelon Heaven] was the gluttony and the hypocrisy. And again, it's like Balloon Nose Blow-Up. I'm trying to drink all the wine that I can and eat all the watermelon that I can. Now can you think of any[thing] more disgusting? And that was the bottom line for it. It was the radio in the background that was more important to me than the image. I'm just sitting like a stupid idiot, drinking wine and eating watermelon, listening to the radio on Easter Sunday.

RC: This set-up, the direct-camera performance, is very different from later more narrative, essayistic videos, such as Mao Meets Muddy (1989), or Nor Was This All By Any Means (1978). In Watermelon Heaven, it’s very simple. Just the camera focused on you eating watermelon.

AR: They're stagnant. There's the camera, it doesn't move, it's on me. In Plastic Bag Tie-Up, the camera does not move. It’s about the television image and controlling that television image. Those others are more narrative, more movie-making. I wasn’t trying to make movies, but I was trying to tell a personal story. [Those were] my attempt to tell a story the way that I wanted it told, rather than told by the major media.

RC: And then there’s Plastic Bag Tie-Up (1972), and Water Plastic Bag (1972). Both very uncomfortable videos in which you and a collaborator seal yourselves, bound, in plastic bags, from which you try to escape for the duration of the video. In Plastic Bag Tie-Up, you’re staging this in a studio at CalArts, but in Water Plastic Bag you’re on the beach. You’re wearing costumes salvaged from some space-themed B-movie . . .

AR: They came from Hollywood. In Hollywood, you can rent all kinds of things. One of [the stores] was going out of business and they had those costumes, obviously from some Buck Rogers 1930s movie. But wow, what an opportunity to get them! So we used those costumes, Lowell [Darling] and Joe Ray and I. We would go around and do all kinds of crazy things, happenings, you know—we would jump out and do a little thing and jump back in the car. No records,no video of it, no photographs of it. Just show up, do a thing, and disappear.

We did one at the Green Hotel [in Pasadena] where Marcel Duchamp used to like to stay. There was a performance there, and we had researched the place before. We figured out where we could come into a window and get up above the stage and drop a rope down and shimmy down the rope. The people there were like, “What’s this?” I stood in the center, and Joe and Lowell covered me with shaving cream. It smelled like hell. I was like this white snowman on the stage. And then we just ran out the back and disappeared. People booed, and some cheered. We would do things like that all the time. And again, there was no record.

Part of the Allan Kaprow happening thing was very Buddhist. Buddhist sand paintings . . . these things are not important. You do them, and then you get rid of them. But now that I'm an older person, I realize that Allan documented everything. I go to the museum in Germany, and they've got all these tires in the center [from Kaprow’s 1961 happening Yard], and I'm thinking, Oh, yeah?

RC: Thinking of you covered in white shaving cream, I've also been interested in your use of the gesture of painting your face or applying face paint, which is something that you use in the two-channel installation Black and White (1973–75).

AR: Black and White was deliberately done that way—two-channel pieces were not something that everybody did. It was my wife, Ann. She was a Scotch Irish girl. And so much was happening around race and civil rights—and there still is. Just one of the reasons why I live in Europe is because I get tired of hearing about race all the time in America. Anyway, we did this piece where I turned myself white, and she turned herself black. That's the whole deal. But it was meant to be like a dance between the two., The way that we [go about painting ourselves] is very different: I'm doing this real masculine, going-to-be-the-warrior thing, and she's doing it like it's makeup, going-to-be-pretty thing. She puts on the Afro wig and I put on the straight wig and the chain around my hands.

RC: So what happened after you graduated from CalArts in 1973?

AR: Well, I'd gotten out and I [no longer had access to the video] equipment. I wanted to go to Cape Verde and find out what my ancestry was. That was the beginning of Black Power, and people were trying to find out who, where, what, and why. Well, fortunately for me, I don't have to look too far. I know where my ancestors are from in Africa and the Cape Verde Islands. But I didn't know anything about it. Nothing. I knew a few words, and there was the Cape Verdean club down the street [in Providence, Rhode Island,] that my grandmother had co-founded, but we were American kids. I decided that I would go back to Rhode Island, where people knew who Cape Verde Islands were, and I could probably raise money to go to Cape Verde. And I did! I got a grant from the Rhode Island Committee for the Humanities, as it was called at that time, thanks to a number of good people who backed me—this was expensive stuff in those days. I got [new] video equipment and went to Cape Verde.

I [went first to] Senegal, and [the airline had] sent my equipment down to South Africa. I had to wait for a month in Senegal. While I was there, it was Easter Sunday, and I was walking past the cathedral. I [thought], Let me go in here and see what Easter Sunday is in a Muslim country. I go and see all these Cape Verdeans. And it was family! It was quite something. And I ended up going to Guinea Bissau, and the revolution was still going on with the Portuguese. I ended up in Cape Verde. It was quite an adventure. And I've got 90 hours of videotape of those years of that whole thing.

RC: Soon after Cape Verde, you arrived in New York City, where you started up your own video-equipment business in a big loft in Chelsea.

AR: It was on 27th Street, right around the corner from Juan Downey's. We did commercials! In fact, I invented the business of [courtroom videography], of Judge Judy and all of that. We had no money, and were trying to pay this rent of $800 a month—which, I know, you laugh at it now. This was a huge, huge loft with three elevators that came into it. I decided I'd call up the New York District Attorney's office, and I said to the guy, you know, you guys [still use these old-fashioned stenographers and typists]. Why don't you do video? And we set up six different [recording stations] around Manhattan for homicide [interrogations]. The camera was in another room [behind] a two-way mirror. And the microphone was a radio on the table. These people would have to be told, “We are videotaping you,” [and] they [would get] all excited! They would turn the chair so that they could be recorded confessing about how they just murdered a baby. And meanwhile, we're in this other room [where] you can just look through the window and see all of this, and everybody in the room was looking at the monitor. Taught me a lot about the way people look at images and the power of television.

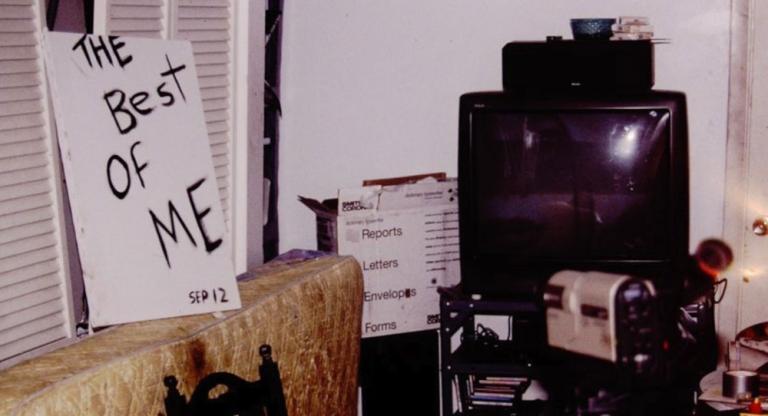

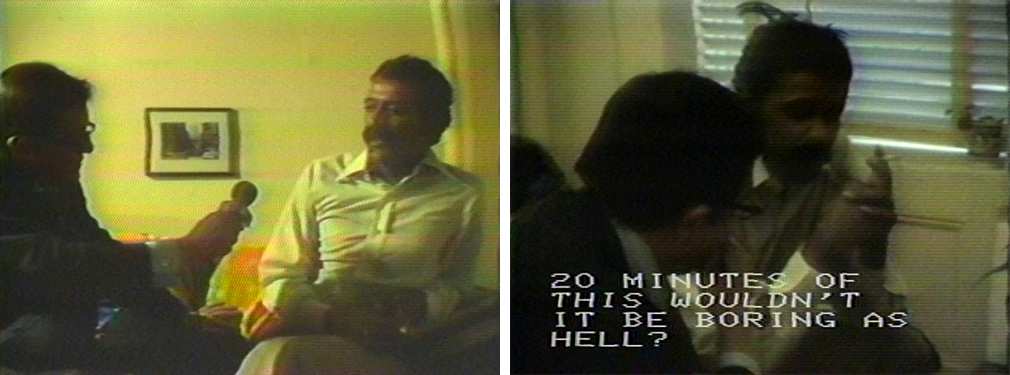

RC: And then, you became the subject of broadcast television yourself, when in 1977 President Carter officially pardoned the conscientious objectors. A local news crew was dispatched to interview you—the iconic broadcaster Gabe Pressman, for those who remember. Gabe arrived with his crew and their film equipment. You were ready with your own video equipment, which became the basis for your video About Media (1977), in which you tape, and later deconstruct, your experience as a broadcast-news interviewee.

AR: I'm sorry I never got to show [Gabe Pressman] that tape. He was a really good guy. And if you notice [in About Media], his two helpers were real assholes. Gabe was the only one who really understood what's going on. He would try to admonish them and they’d be back there sighing, so I wrote “sigh” underneath the picture. We were in control, we didn't miss anything. They had to stop filming and move the lights, and [meanwhile] my partner Mike Frenchmen is recording all of this stuff. At one point, the guy says, “Aw, we missed it,” and Frenchmen says, “We didn't.”

There's the news, and then there's the reality of things. I suspect that that's what all those MAGA people are talking about. They're getting it, but they don't get it. There's the reality of things, and then there's the public media [account] of things, you know, and the public media [account] doesn't really tell the truth. It has an agenda, and that agenda is to make money for the corporation.

RC: Your last video-art piece, before you fully turned your attention to painting, was Mao Meets Muddy (1989). You documented your trip to China with your good friend, the painter Frederick J. Brown. He was having a major retrospective there, at the National Museum of China.This was in 1988, and of course the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were the next summer.

AR: I made it after the 60 Minutes [reporting on Frederick Brown’s exhibition]. They did their little piece; It was a nice little piece, but I did the piece about what we were doing. It was more than just about showing off art to the Chinese. It was a real cultural exchange.

RC: At the conclusion of your tape, you show yourself crying on camera, hearing news of the protests and killings in Tiananmen Square. It brings it back to Balloon Nose Blow-Up, in a way. Your face tightly framed by the camera, looking directly into it.

AR: I was crying for that man. You could see how hurt he was. He's crying, you know? Wow. How can you not empathize with him?

RC: Why did you stop making video art?

AR: Couldn’t make any money! I always wanted to be a painter as a child. I liked the idea of painting, even though Allan Kaprow thought it was really weird. Dear Allan, when he was dying I was in Los Angeles, and I went down to see him. I got there, and his wife said, “I don't know if he'll see you, Tony.” He was on his last legs. I went in there, and he held my hand, and we talked. He would go in and out. He said, “What are you doing now?” And I said, “Well, I’m kind of a successful painter.” He damn near sat up in this death-bed hospital bed and “Yeah? Well, you deserve it.” Now many years later, I was in Germany with his wife, and I told that story around the table. She said, “Well, how do you think he meant that?” And then I reflected, Hm, maybe Allan thought it was a curse.

RC: But I can see a continuum in your video and painting, especially your most recent series.

AR: Well, you know, [initially] I was doing mostly abstract stuff, but always with the political message in it. Like slave laws written around the sides, and African motifs, and so on. Then I thought I would like to do some portraits. And then they killed George Floyd. That really . . . it was the arrogance of it, the cold-bloodedness of it. You're sitting there, you've got witnesses and you don't give a damn. “I'm just killing this nigga and I don’t give a damn.” So I started doing a series. The latest one I finished was of Tyre Nichols. But I'm continuing. I'm doing a self-portrait right now where I'm screaming. I’m still screaming. All these years later, I’m still screaming.

“Nor Was This All By Any Means: A Career-Spanning Series with Anthony Ramos” runs April 20–28, including programs at Electronic Arts Intermix, DCTV Firehouse Cinema, and the Colloquium for Unpopular Culture at New York University with Anthony Ramos appearing in person, as well as a showcase of Ramos’s early video-performances, free to stream online at eai.org.