The Museum of Modern Art’s celebration of the uniquely charismatic actor, filmmaker, and writer Pierre Clémenti continues with his onscreen tour de force, Bernardo Bertolucci’s Partner (1968). For the decadent auteur’s third feature, he turned to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1846 novella, The Double, for his source material. Bertolucci uses the writer’s biting portrait of a young man tortured by class rejection, anger, and, perhaps, schizophrenia—a literary rebuttal of Gogol in much the same way Notes From Underground (1864) would take Lermontov to task for his angsty nihilism—to tell a story of emerging political consciousness that takes the form of a seductive doppelganger.

Giacobbe (Clémenti) is a frustrated college student who is saved from suicide by a man who looks exactly like him. This other Giacobbe is suave and capable of action; qualities Giacobbe I lacks. As the line between the two men begins to erode, Giacobbe II and his revolutionary ideas take over. He builds a guillotine, teaches his fellow students how to make molotov cocktails, and sets loose a type of theatrical anarchy on the streets of Rome.

Following La Commare Secca (1962) and Bertolucci’s breakthrough Before the Revolution (1964), Partner is a playful, cinematic rendering of the highly charged political atmosphere in Europe in 1968. In the director’s first color film, he uses large swaths of monochromatic paint (particularly the reds and blues of the Viet Cong’s flag) in pop art fashion. The mise en scène bounces between Bertolucci’s sumptuously dark photographic grace and sequences of a more performative and silly nature. These latter sequences are like documents of experimental theater unleashed on an unexpecting bourgeois world—most memorably among them, a young man walking blindfolded into oncoming traffic.

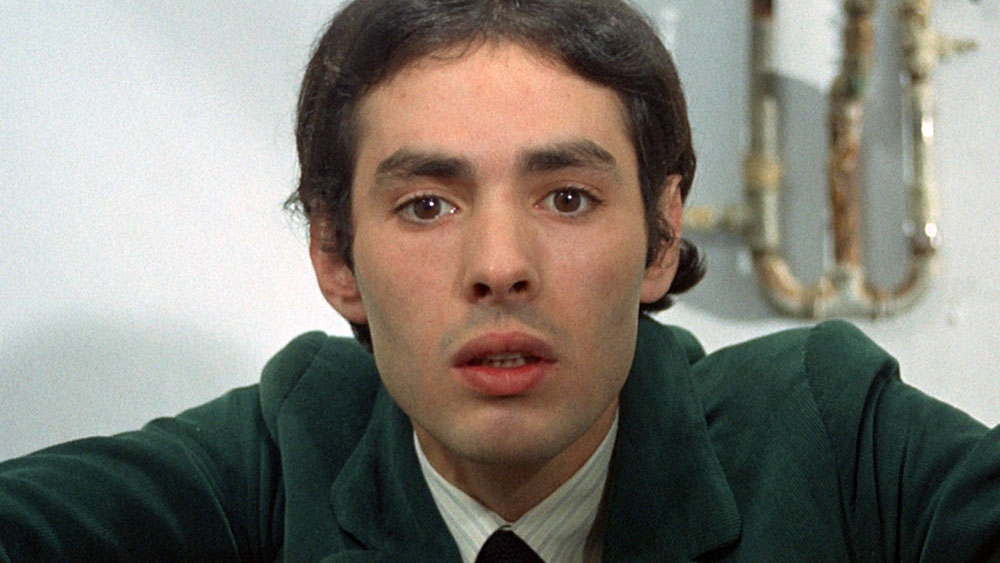

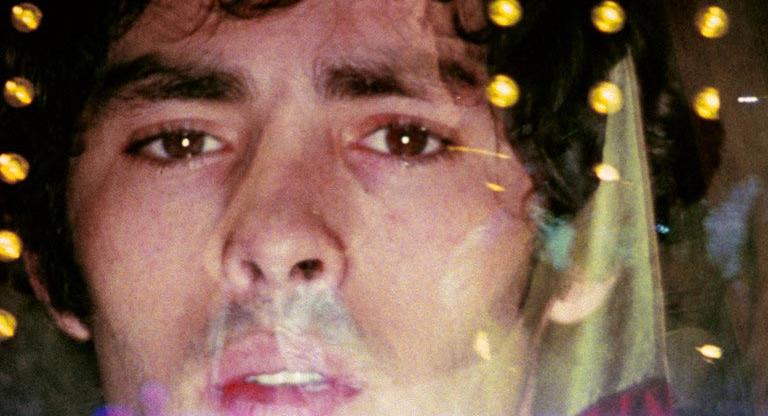

Partner is a film of imaginative vignettes and dazzling choreography, but its greatest achievement is its ability to propel its narrative through a series of purely cinematic digressions. Holding it all together is the magnetic presence of Clémenti. The actor, who was imprisoned in Rome in the early ’70s, is able to effortlessly shift from languid to ferocious without warning. Often he faces himself on screen, and the subtle differences he achieves to differentiate his personas are impressive. In The Double, Dostoevksy writes, “The door from the next room suddenly opened with a timid, quiet creak, as if thus announcing the entrance of a very insignificant person . . . ” and this is the first Giacobbe we meet: a guppy-mouthed, buttoned-up, listless intellectual loafer, whose flailing rage is both comical and pathetic. For his revolutionary counterpart, though, Clémenti’s hair is slightly mussed, there is a sly tension in his gloriously cadaverous cheekbones, and his eyes smolder with mocking scorn; his electric presence anything but “insignificant.”

Partner screens this evening, October 25, on 35mm at the Museum of Modern Art as part of their Pierre Clémenti retrospective.