Jacques Tourneur’s final horror film, Night of the Demon (1957), is also the last of his films to be generally regarded as something of a masterpiece. This reputation stands despite the troubled history of its production, with editorial interference from producers who both added scenes—the shots at the beginning and the end of the film revealing the demon in cartoony close-ups—and, for the U.S. release, retitled “Curse of the Demon,” cut others. It’s likely they hoped Night of the Demon would be part of the ‘50s movie monster revival; the film originally opened in a double bill with one of the British-made Hammer horror films. But that schlock never interested Tourneur, whose earlier horror pictures for RKO were initially celebrated for their sophisticated minimalism.

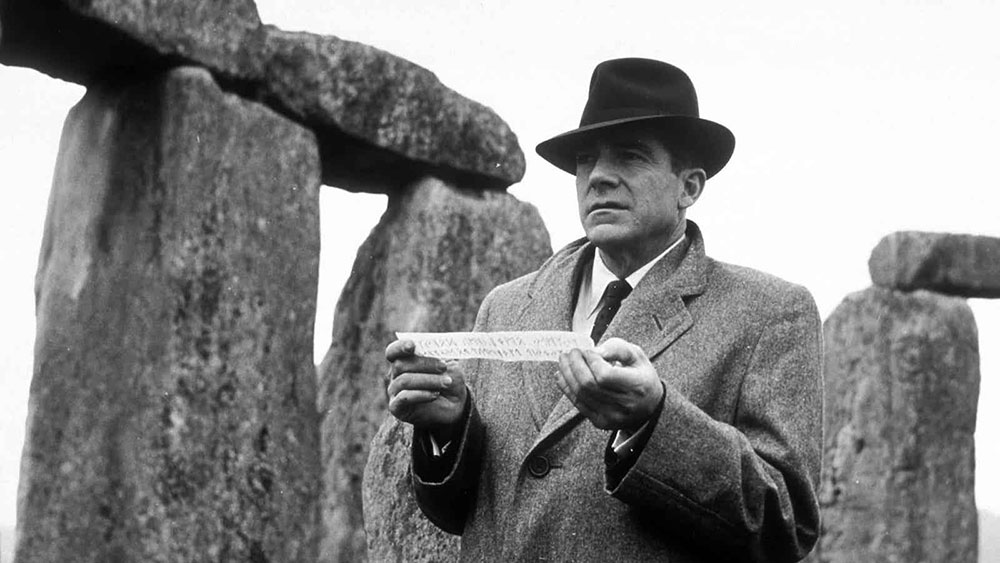

Night of the Demon is exceptionally crafted: the décor is extraordinary, as is the editing. Tourneur’s approach to lighting, and especially the backlighting of scenes, is superb. Certain images will likely be seared into the viewer’s memory: the wind in the trees during the party scene, the close-up of the hand on the stairs, the excellent finale. Star Dana Andrews is amazing here as an American professor who becomes enmeshed in a British cult conspiracy: drunk, disturbed, and easily flustered. There’s a great deal in common between the two films Andrews made for Fritz Lang and Tourneur in the late ‘50s: While the City Sleeps (1956), Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), Night of the Demon, and The Fearmakers (1958). His indifference to the mysteries unfolding in all of those films is key to their charm, especially when their quality is a bit lacking. All four films share a structure that alternates in its convictions from scene to scene, leaving us guessing as to the reality of the situation.

Hollywood produces at least three kinds of actors. There are automatons like John Wayne or, in a different sense, Cary Grant, who reliably churn out instantly likeable and infinitely repeatable performances. There are hams like Emil Jannings, whose task seems to be to make acting look like the hardest profession in the world. And finally, there is a crop of proto-Bressonian actors like Andrews, totally neutral in expression and affect, who seem to make the most honest gesture possible in every scene.

Night of the Demon screens this afternoon, May 11, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of the series “The Lady at 100: Columbia Classics from the Locarno Film Festival.”