I happened upon Kani Releasing with their February Blu-ray release of a lesser-known Lino Brocka film, Cain and Abel (1982), for which the auteur struck another satisfying balance between his work-for-hire and work-for-self styles. Only a month later, Kani released another Filipino title, Dwein Baltazar’s more recent Oda sa Wala [Ode to Nothing] (2018), and just after that, Daisuke Miyazaki’s Videophobia (2019), which Kani describes as a “paranoid techno-thriller.”

Kani’s selections are thrillingly hard to place in terms of tone, genre, and local context. There’s no shortage of “boutique” home video labels and distributors—even ones that claim to specialize in “Asian cinema,” as Kani does—but few operated from a non-Western perspective. The two-person home-video label and distributor has already set itself apart with its first four releases, each with specific milieus that the films don’t attempt to universalize.

Behind Kani are co-founders Ariel Esteban Cayer (a Fantasia programmer) and Pearl Chan (Good Move Media’s sales and acquisitions manager), both based in Hong Kong and with roots in Canada. We spoke about contextualizing films from off the beaten path.

Aaron Hunt: What’s the story behind the name?

Ariel Esteban Cayer: We named the company after kani, the Japanese noun for crab. This is what Yasujiro Ozu called his custom-made crab-leg tripod that he used to shoot his famous tatami level shots that everyone knows and loves. It seemed very fitting because we wanted to release and discuss Asian cinema at a so-called tatami level—from a perspective that would be perhaps more grounded, knowledgeable, less Western, and less from the outside. I think we say in our little description that we want to “level the gaze” on some of these films.

Pearl Chan: The name stuck before we even knew what format it would be.

AEC: Yeah, it was going to be a newsletter at one point.

AH: Your name feeds into the ethos of the company in such a holistic way. I was going to ask you more about that bit of copy, “leveling the gaze . . . ”

PC: When we speak to Japanese people who have seen our upcoming title, Tremble all You Want (2017), a Japanese romcom that subverts the genre, they go, “That’s so local. Will it really work overseas?” For the North American industry, Tremble’s still a risk, even though it’s a pretty big film. Traditionally, only specific genres—like arthouse, and Japanese and Korean horror, etc.—have been brought over for the Western gaze.

AEC: We tend to gravitate toward work that requires some unpacking and explaining—that feels local to us. That’s not to say the films are difficult; so far what we’ve released is fairly approachable, hovering between arthouse and genre. But they all have layers of social politics or cultural specificity that do require explaining, which a Blu-ray package can do. Companies we work with are always surprised when we ask about X, Y, or Z film instead of another Shinya Tsukamoto or Sion Sono film, which—nothing against those.

PC: Even before we’ve asked these companies, they’ve already created a list of films they think would be interesting to people in the West. You end up with these availability lists that are incomplete. You’re like, “Well I thought you had this film?” And they say, “Oh yeah! We just didn’t think you were interested.”

Take Cain and Abel and the subtext of martial law. The poverty, haciendas, and landowning classes. These are things that in one hundred years maybe even people in the Philippines won’t remember. If you’re from the States, even though your country may have perpetuated some of these issues overseas, you’re not aware of them. Even though the films play perfectly well on their own, we may miss some of their original intentions because we’re no longer living or never lived within that context.

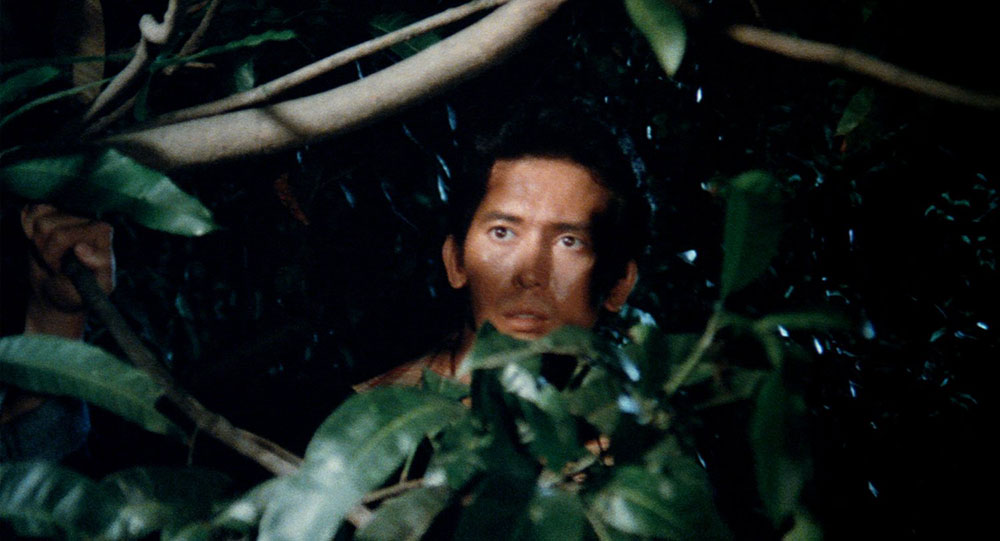

AEC: Cain’s a good example of the work we’re doing in the sense that it has all these sociopolitical dimensions that are well worth exploring packaged within what is arguably a commercial, pulpy melodrama that turns into a kind of revenge-action film, which is a mix very specific to Filipino cinema and the larger context of Lino Brocka’s filmography.

PC: Cain and Abel was a screening print from ABS-CBN from the ’90s. Maybe someday we’ll have nightmares about the OCN [original camera negative] showing up, or maybe someday we’ll scan the OCN and make a better restoration. But what if neither of these happens? The Philippines is incredibly humid, prints deteriorate . . . We didn’t want to wait until somebody else was going to come along and spend $100K to restore it, which I don’t think anyone has ever done for a Filipino film. And Cain and Abel was not a priority [for restoration], nor [were] Brocka’s more minor films or more minor Filipino filmmakers. When Cain and Abel premiered in Venice, it got a pretty scathing review that was racist. It basically said that it was only acceptable to third-world audiences.

AEC: I believe it was something like “third-world palettes”—horrible phrasing.

PC: So of course there’s no camera negative of this film in France or Italy.

AEC: As far as we know.

AH: How do you feel about centering North American audiences? A US release really bolsters films, but because of the unsavory ways the market works.

AEC: If a film comes out in New York and LA it can feel like it’s been released worldwide, which of course is a very Western-centric way of looking at things, but as you said, it’s how the industry works—there’s France and then there’s what’s happening in North America, mostly the US. We do hope and think [North America is] a good audience for these editions and thankfully there are only so many Blu-ray region codes. When contracts allow us to do region-free Blu-rays we do.

PC: Some of the films we’re working on are not going to get another home video release. North America was kind of a no-brainer because that’s where we’re both from, to an extent. The other option would be here in Hong Kong, but there doesn’t seem to be a collector culture around locally produced Blu-rays for various reasons. But we’re also doing a lot of work on OCN’s [Vinegar Syndrome’s “sister company”] Hong Kong films. We did a release of Herman Yau’s Ebola Syndrome [1996], a pretty infamous Category III [18+] film. We spoke to the director and tried to put together a way of presenting it that wasn’t just, “Oh my god! This exotic Oriental film!”

AH: Can you talk about any of your upcoming releases?

PC: We’re releasing two restored films by Masashi Yamamoto—one from 1987, Robinson’s Garden, and [another from] 1990, What’s Up Connection. The former was shot by Tom DiCillo. Yamamoto had met Jim Jarmusch at one point and asked him if his cinematographer was any good. We have them both on Robinson’s Garden [in a video interview] talking about their experiences.

AEC: DiCillo shot it right after Stranger Than Paradise. So Robinson’s Garden has a little of that early-Jarmusch flow and feel, which is exciting to find in a Japanese film from the late ’80s.

PC: Robinson’s Garden premiered in Berlinale Forum, where he also met a bunch of Hong Kong and Taiwanese filmmakers; Hou Hsiao-Hsien was there with Dust in the Wind, Edward Yang was there with The Terrorizers, Shu Kei was there for Soul [all 1986], which Hou Hsiao-Hsien actually acted in. Soul is also Chris Doyle’s first film in Hong Kong. Shu Kei invited Yamamoto to Hong Kong and housed him for a few days, which is where he began plotting What’s Up Connection, a Japanese film shot in Hong Kong.

AH: Was there something specific you weren’t seeing in other home video labels that you wanted Kani to make up for?

PC: I work as a sales agent for East and Southeast Asian films. I see really good films that don’t get picked up for a variety of reasons, Southeast Asian films in particular. I think curation is really important, but it can also restrict things. Festivals tend to have one slot for Southeast Asia. But Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong each get five slots. For Hong Kong, this is partially because it has an ETO [Economic and Trade Office], which funds festivals in a way that requires them to fulfill quotas for the kinds of films screened. A lot of governments don’t have these programs. So we want to support cinema that has fallen through the cracks for reasons beyond quality.

My work is sometimes very lonely, because you talk with a programmer, a distributor, a cinema, etc., before you get to the audience. Making a Blu-ray, it’s exciting to make things for real people—we make an object, the object reaches [a] human. I want to do something so completely direct . . . I don’t want to have to go through what may work according to a programmer for their specific city and community. I just want to make something available so people can get it. I think curation is really important, but it can also restrict things.

Kani Releasing is a new home video label and distributor, in operation since 2021. Tremble All You Want (2017) will be released on July 1 and both Yamamoto films later this year.