For the past week, Anthology Film Archives has hosted El Cine Quema: The Films of Raymundo Gleyzer, a near complete traveling retrospective of the militant Argentine filmmaker programmed by Steve Macfarlane. With brand new restorations, audiences have been able to view the work of a filmmaker seldom spoken of when discussing the major figures in Latin American "Third Cinema." Through Gleyzer's films, one witnesses his native Argentina's descent into fascism and political repression. His films are direct, serving as a call to action and resistance against those in power. Throughout the retrospective one can see the transformation in Gleyzer's work that eventually leads to films such as Mexico: The Frozen Revolution and The Traitors, both extremely critical of their subjects and subsequently banned by government censors. Along the way he become a member of the PRT, a Marxist-Leninist party in Argentina, and also formed Cine de la Base, a collective that weaponized filmmaking in the fight against inequality.

Following her husband's "disappearance" in 1976 by the military junta, Juana Sapire fled her native Argentina, escaped to Peru, and eventually settled in New York City with her son Diego. A filmmaker herself and frequent collaborator in Gleyzer's films, Sapire has dedicated herself to not only spread awareness of her husband's work but continue the cause her husband had been so passionate about. With a cultural center, a high school that offers a free education in Argentina, and his films receiving recognition throughout the world, his legacy continues, ensuring he will never completely disappear.

I met with Sapire ahead of the series' conclusion on February 28 to discuss how she met her husband, his early work, his gradual transition into more militant filmmaking, and her role in his films and subsequent escape from the dictatorship.

AC: I was hoping we could start with the early films that are included in this retrospective, such as The Land Burns, It Happened in Hualfin, Pottery Makers, and Quilino. What made Gleyzer want to venture out into these rural areas to document the people that live there and have their stories heard?

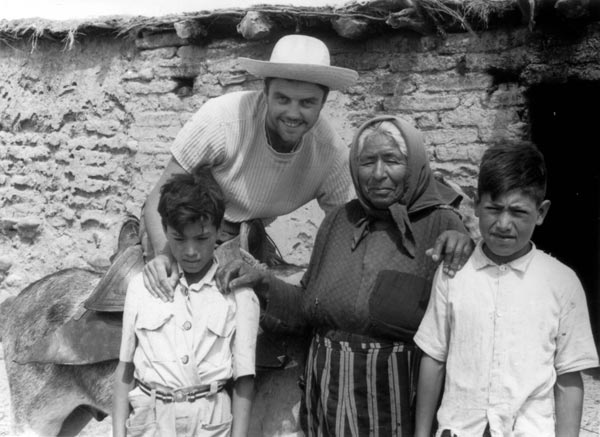

JS: Because your sensibility tells you so, that's what you love to do, that's what comes from your heart and spirit. When Raymundo went to shoot The Land Burns, he was 21 and studying filmmaking in the city of La Plata because Buenos Aires didn't have a film school at that time. He was a very pragmatic person. His classmates noticed immediately that while they were studying theory, Raymundo was already out shooting films. He had a 16mm camera, and his idea was to go hitchhiking with a friend, where they eventually reached Brazil. It was hard, they had no money, and Raymundo was asking consulates and embassies to give him film to shoot with. One day, he woke up and saw that his friend had left with all the money, but he didn't quit — he continued by himself despite having no money. To answer your question: you go to those areas, where they eat tortillas with nothing in them, and Raymundo would eat what they ate, he would take his time, and he would be one of them. He was a very sensitive person, he didn't just go to shoot film and leave, he would live with them because he loved it. He wanted to be with real people and was asking them to learn from them, that's what he liked.

When we got together as a couple, I joined him because I found it very interesting. I was also studying film at a different school.

So did you meet in film school?

No, we met in high school when I went on a double date with a friend. I think she liked Raymundo, and he brought a friend that I didn't like at all, so that didn't prosper. We met again on a street in Buenos Aires that was filled with theaters. He was always carrying a camera, and I found him more interesting than anyone else. Raymundo came from a very poor independent theater family. They didn't have much, but they were very cultured people, always reading and performing works by playwrights such as Chekhov. They had no money for a babysitter, so he would go to the theater with them, and he was fascinating. We would talk for hours with nothing to do, and it was the most wonderful thing.

You mentioned before that he was a very friendly guy, and I wanted to talk to you about that because you can see that in his movies. His subjects are not afraid of telling him how they feel about their living situation, they aren't shy.

When you live and get to know Raymundo, he had that charm and light of sincerity in his eyes, he was very trustworthy. I am still in touch with the little girl in It Happened in Hualfin, Elinda. She says "I always remember Mr. Raymundo because he let me sit on his lap." While her mother was weaving, Raymundo and his partner at the time Jorge Prelorán would just sit there and do nothing. In the countryside, you don't talk as much as you do in urban areas. If someone needs to tell you something, they will, but there is no small talk. He would get to know them, ask them about their lives, just let them talk, and although sometimes they would get difficult, what can you do about it? Going back to Elinda though, we've stayed in touch, and she's become a world-renowned artisan, and she remembers Raymundo bringing her a pack of cookies with all the love in the world. It's incredible that she still remembers him and became famous for her own work.

Did you watch They Kill Me If I Work, And If I Don't Work, They Kill Me?

I did, yes.

One day, the bell rings at Ernesto Ardito and Virna Molina's (directors of the documentary Raymundo) house and to make it short, a woman appears and says she's so and so's granddaughter and that her grandfather was in a film but had passed away before she was able to meet him. We show her They Kill Me If I Work, and her grandfather is one of the protestors shown in the film, and she began to cry. People call me from all parts and get inspired when I show Raymundo's films. No one in Mexico had ever seen Mexico: The Frozen Revolution because Luis Echeverría (President of Mexico at the time of shooting) had considered Raymundo persona non grata.

What did they say in Mexico when they finally saw the film?

There were huge lines, we screened it as part of the Ambulante Documentary Film Festival. Gael Garcia Bernal said on television that if there was one film you needed to see during the festival it was Mexico: The Frozen Revolution, which is great when you don't have the means for publicity. So many young people came that knew what had happened in the Tlatelolco massacre but hadn't seen it on film. When the film ends with the music and the photos of the students the crowd stayed silent. I don't remember what year it screened but it had been banned for 40 years.

Some of those images were new to me as well.

You see? Raymundo was always direct, even at the beginning with The Land Burns, with the child turning the Christ portrait away. We've been criticized since then! Mexico: The Frozen Revolution was only shown once in Argentina because on that day Mexican officials were in Argentina, said to take it down, and the Argentine government obliged. This must have been in 1972 when I was pregnant with my son. We went to the newspapers to ask why and they responded that the Mexican consul saw the film and stated that while everything in the film is true they didn't want to be shown in a negative light. I remember asking how it was possible for Mexican officials to have that type of power in Argentina! When it was finally shown 40 years later it felt vindicating, no one is going to stop me just like that.

What made Gelyzer decide to go to Mexico to film The Frozen Revolution, and how was it able to be produced without tipping off PRI officials?

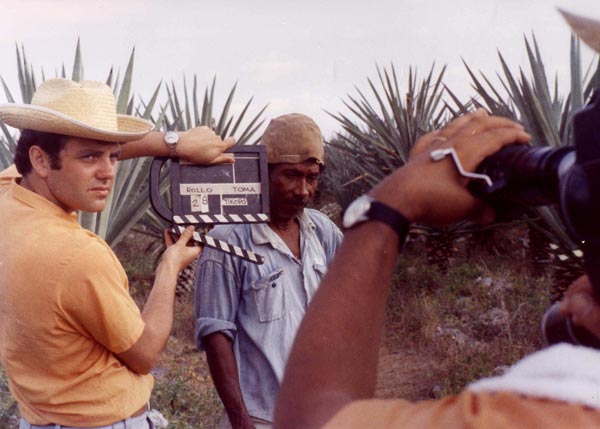

You sound so innocent asking this question! We did our work no matter what obstacles we could potentially face and had planned to make a film in each Latin American country. Raymundo would say that he is Argentine but also belonged to all of Latin America. Obviously, it did not come to fruition, he was captured when he 34 years old. We were in Mexico for two months researching with Bolivian filmmaker Humberto Ríos and his wife, she a historian and Humberto, being one of Raymundo's former professors, operated the camera. We were supposed to be shooting for German television, and that's how we were able to gain access to certain figures in the film.

We began shooting in Chiapas, and the idea was to film without asking permissions, we had everything we needed. The Mexican authorities told us that there were two ways to shoot a film there: either someone accompanies you and oversees the production, or you show them everything you filmed before leaving the country. We didn't have space in the car for another person, so we lied and said we would show the film before leaving. We drove throughout the country and it was a wonderful time. Paul Leduc joined us because we wanted a Mexican perspective and he shows up in the film as well. Back then, we didn't know if what we were shooting was any good and hauling that equipment in the Mexican sun was difficult. With the help of a flight attendant friend of ours we would transport the film to New York and hand it to Bill Sussman, who was vice president of a developing lab, that he would say did the best fucking job in the world. We would call him and he would tell us that we were getting good footage and should continue and in return he would send us new equipment with the same flight attendant.

One day, Ríos set the camera up on the tripod and it crashed to the ground. Rios was mortified, apologized to Raymundo, and said he was going back to Argentina. The sun in Mexico is brutal, especially if you're shooting for eight hours, but Raymundo was a trooper. We went back to where we were staying, Raymundo sat down in the sun and tried to fix the camera. He made a visual note of where every part was supposed to go, started hitting it with a hammer, and later put it back together. With that, we marched on and finished the film.

You mentioned that the film was only shown once in Argentina, what happened afterwards?

JS: We started showing it clandestinely at factories and schools. Legally, we couldn't show it but who gives a damn about that?

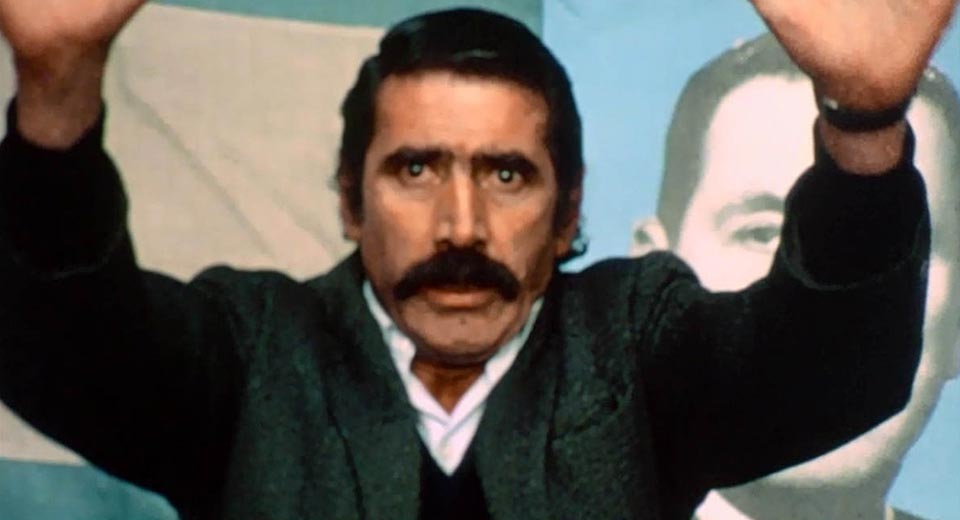

Regarding The Traitors: it's Gleyzer's first and only fiction feature. Why did he decide to pivot from non-fiction filmmaking on this occasion? The events depicted in the film are based on real events.

We had a friend named Victor Proncet who wrote a short story about a corrupt politician that had kidnapped himself in order to be with his mistress. Raymundo gained his permission to use the story and transform it into the story of a corrupt union leader, among other things. He collaborated with Álvaro Melián, who recently passed away, to create this type of docufiction. Anything said by someone in uniform in the film is taken from newspaper articles, so they couldn't deny anything. For example, the burial scene that takes a surreal tone was taken from someone's accounts. Raymundo started going deeper and deeper into this story of these corrupt leaders, which at the time was extremely dangerous and still is in Argentina. These union bureaucrats would announce a strike months in advance without solving the issue and toyed with people's lives. Just crazy things that were all true and for that reason they still show The Traitors and I'm more than happy to share Raymundo's work with any cultural institution in Argentina that asks for it.

One thing I noticed watching Raymundo's earlier work in comparison to his later work is that it's not as radical or militant. What marked that changed in Gleyzer's filmmaking?

It Happened in Hualfin and Quilino were done in collaboration with the aforementioned Jorge Prelorán, an old classmate. Jorge was a good filmmaker and a good person but was never as politically involved. He was content filming these communities and getting a great shot. Since Raymundo was interested in speaking to these people as well as filming them it was considered a more political gesture. So, Quilino was finished by Prelorán and It Happened in Hualfin was finished by Raymundo.

And that's something that you notice if you put them side by side. There is a stark political difference between the two despite their similarities.

Back in those days we also used to collaborate with Ana Montes de Gonzalez who was a catholic anthropologist. Raymundo was a Marxist-Leninist and so they would have their differences while editing the films. However, they both admired each other greatly.

The later films like Swift, Don't Forgive, Don't Forget, and They Kill Me If I Work, And If I Don't Work They Kill Me are much more Marxist.

It was an evolution. We aligned ourselves with the PRT (Workers Revolutionary Party) in Argentina as well as the ERP (People's Revolutionary Army) and you start shaping your ideology. The PRT would buy notebooks or milk and distribute it to schoolchildren or others that didn't have any and would be beaten for it by the police. We were so innocent at that time. The PRT would normally make flyers to describe their actions but eventually Raymundo suggested to make films about the party. Some of those early shorts are what became Swift for example. Don't Forgive, Don't Forget came from our disgust over the events of the Trelew Massacre and we knew we had to make a film and we filmed it in our house. Why wait for funding from an institution when you can just go out and do it? You have to make sure you have a clear idea of what you want to say in your film, you can't just have footage of protesters in the streets, there needs to be a message! It's difficult, but you must make something that will stay in your heart, remain in your mind.

I haven't asked you, but I wanted to know what your specific role was in these films.

I was mainly the sound mixer but I was also a camera operator and impromptu storyboard artist at times. I remember when we were in Greece and Raymundo gave me this complicated direction for the camera but I was the sound person! I would do it anyway and say it came out perfect. At that time, we were working for a news program in Argentina, we'd send footage back to them, and that's how we were able to live in Europe for two years. My main title was sound person but I did everything back then.

Could you talk more about Cine de la Base? How did the collective work?

When we were in production for The Traitors was when Cine de la Base really began to come to fruition. The core group was about 8 people. In The Traitors, there were 110 characters and we had no money so the actors were mostly people affiliated with the PRT. Raymundo wanted to film in settings we would never get permits for and try to get what we could! We didn't have money so we would pay the actors and crew in meals. Everyone was compensated the same and no one complained. Unfortunately, the police also had a copy of the film and were able to track some of the actors due to their role in The Traitors. They also had been tracking Raymundo for years at that point.

Why do you think it's taken so long for Raymundo Gleyzer's films to have a retrospective such as this one in the United States? There are filmmakers from other countries in the region with similar politics that seem to be recognized more.

Good question. I've shown his films in various colleges around the country, but this is the first time he's having a series in New York. I'm not good at self-promoting though and don't feel it graceful if I were to say that my husband was this grand figure. When you escape death in Argentina with a 4-year-old, only 100 dollars, you have to be strong and you can't cry in front of your son... that stayed with me for a long time. I didn't want to be found and it was also just a painful experience at that time. It was painful to explain to people what a desaparecido was back then. I remember having to go to the immigration office to stay in the country, trying to explain it with my child by my side. I had to go to the Argentine consulate every month to prove that I was alive to them and one day a woman working there asked me how did I know Raymundo wasn't just traveling. I was going to tell her off but my son simply told me, "Mom, don't worry, she doesn't know her head from her ass." With what is happening in the world now it all just feels like a cycle of what happened then.