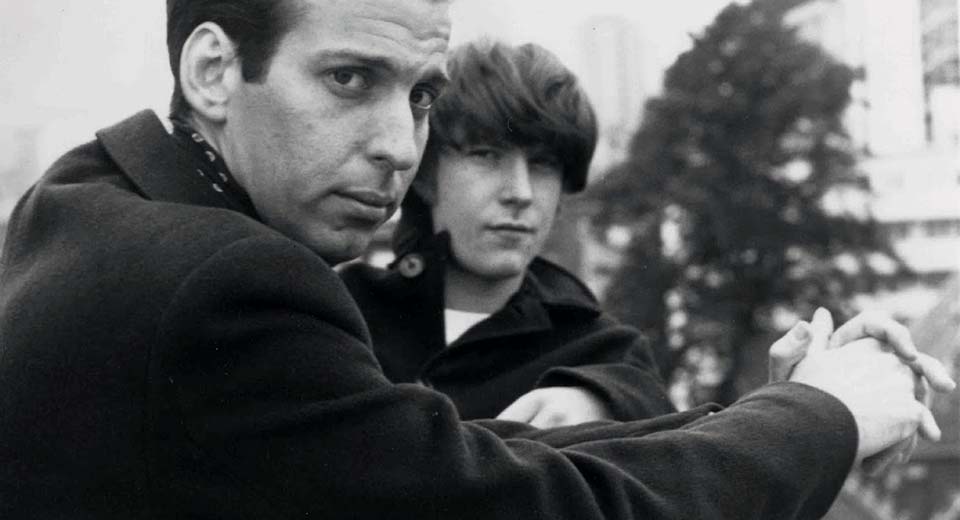

In the spring of 1963, between "Love Me Do" and Ed Sullivan, The Beatles' manager Brian Epstein invited John Lennon on holiday in Spain. Rumors hounded Lennon for years afterward that he had enjoyed a fling with the half-closeted Epstein during the trip. He would later invite speculation and dismiss the gossip while always delighting in jokes at the expense of Epstein's sexual orientation. It seemed he genuinely loved the man in some deep way, but couldn't square his self-reflexive feelings towards Epstein's queerness. Christopher Munch masterfully captures the psychosexual tension between the two in his dramatization of the Spain trip, The Hours and Times (1991). The film is easily the most engaging fiction film made about The Beatles, though the field couldn't accurately be called competitive.

Perhaps the most deserving recipient of the "Fifth Beatle" designation, Epstein saw with supernatural clarity the group's immense commercial and cultural potential. The son of music shop owners, Epstein took the group from beer halls to America and then around the world in less than five years, before dying of a suspected suicide in 1967, an event which Lennon claimed hastened the group's unraveling. But as he reshaped the world by shaping its greatest musical phenomenon, Epstein was blackmailed and beaten more than once while seeking rough trade in an era when homosexuality was still outlawed in the UK.

David Angus plays Epstein as a soulful aesthete simultaneously processing his lust and awe for Ian Hart's brash Lennon while the latter belittles and seduces him during capricious outbursts. In Munch's telling, the two speak frankly about Epstein's homosexuality, with Lennon claiming curiosity about the anatomical details of gay sex before lapsing into angry jokes. Epstein attempts to save face while awaiting the right time to act upon his desire. Angus is patient, all eyes, while Hart is mostly mouth. Munch wrings an incredible amount of visual intrigue from two characters who spend most of their time talking in hotel rooms. By emphasizing closeups filled with longing, Munch avoids the pitfall of two-hand films that feel like recorded theater.

Munch's speculative fiction deepens our collective fascination with the Beatles by calling for the turning over of ossified pop mythos. We'll never know what happened in Spain, and it doesn't matter. What matters is the intersection of commerce, art and sex trafficked by pop stars, upon whom we project our deepest fantasies.