It’s easy to drown in superlatives about Noriaki Tsuchimoto’s documentaries—how they convey the force and scale of injustice and suffering. It is far more challenging to discuss how they remain, even if only in brief moments, buoyant and joyous in the face of such hardship. Still fairly obscure outside Asia, Tsuchimoto is most widely known for the films he made in Minamata, a city in Japan’s Kumamoto Prefecture that experienced an outbreak of severe mercury poisoning, discovered in 1956. This poisoning came to be known as Minamata disease, and the culprit was the Chisso Corporation, which had discharged polluted wastewater into the ocean for decades. These films tackle, with excruciating directness, the protracted fight by Minamata victims to receive compensation from Chisso, the disabling effects of the poisoning on their bodies, the ostracism they experience as a result of their disabilities, and the ecological destruction wrought upon the neighboring inland Shiranui Sea.

Films like Minamata: The Victims and Their World (1971), an urgent plea to raise awareness of the issues in Minamata, are unmistakably the work of an incensed director. But, by the time Tsuchimoto makes The Minamata Mural (1981), which follows a husband-and-wife team of painters, Iri and Toshi Maruki, as they create large murals of the victims, the grief and rage simmers down into a recognition that those with Minamata disease were, in the end, simply going on with their lives. It was Tsuchimoto’s ability to find “paradise in the sea of sorrow”, to borrow the title of Michiko Ishimure’s 1972 book about Minamata, that perhaps explains why he was able to maintain such a long commitment to documenting the people, landscapes, and seascapes of this community without succumbing to despair.

Tsuchimoto also saw the importance of film as a way of building relationships. As an independent filmmaker, distributing his films often meant literally trekking across the country with them, hosting screenings wherever he was able to: in town halls, community centers, even outdoors. He traveled to remote islands in Japan to show the Minamata films, and when Minamata disease broke out in First Nations communities in Canada, he brought the films there too in hopes of sharing what they’d learned about holding corporations and the government responsible. In an oeuvre that can initially seem to be focused almost exclusively on Japan-specific issues, there are myriad moments that connect Japan to the rest of the world. The Minamata Mural explicates Chisso’s involvement in Japanese imperialism in Korea, Exchange Student Chua Swee-Lin (1965) advocates on behalf of foreign nationals in Japan, and films abroad like The World of the Siberians (1968) and Afghan Spring (1989) consider where the boundaries of so-called “Asia” lie.

A retrospective of Tsuchimoto’s films—the first in the US—at the Museum of the Moving Image allows viewers to survey the full sweep of his career. It extends from his subversive early works at the PR firm Iwanami Productions, to late masterpieces like Umitori: Robbing the Sea at Shimokita Peninsula (1985), which chronicles a different coastal community fractured by the expanding nuclear power industry. I conversed via email with its programmer, Max Carpenter, about the work of bringing this retrospective to the US, what it can tell us about its director, and about documentary filmmaking as an act of experimentation, solidarity, and perseverance.

Emerson Goo: I think anyone passionate about Noriaki Tsuchimoto has gone on their own circuitous journey of discovering his work, since he’s so underseen outside of Japan.

For myself, it must have been at the end of high school when I first heard about him. I had been looking through lists of top documentaries, and saw that John Gianvito listed The Shiranui Sea (1975) as one of his all-time favorites. [Gianvito will be at MoMI to introduce Prehistory of the Partisans tomorrow afternoon, 11/13. –Ed.] I remember being intrigued by the descriptions of the films he made, and how they spoke to similar environmental justice struggles in Hawaiʻi. But it would be a while before I saw anything by Tsuchimoto—the first film I saw was Minamata: The Victims and their World, a few years ago.

What was the first movie by him you saw? And when and where did you see it?

Max Carpenter: I can't say for certain the first time I heard about Tsuchimoto. Without watching Victims, I absorbed basic info about it through cinephile culture osmosis many years ago. It seemed like an “important” film that I wanted to get around to sometime, but the humorless gravity of the endeavor did not make for an urgent selling point. When I watched it for the first time in 2019, I was blown away by the range of emotional depth. Yes, it's devastating, but that's the surface—that's the price of admission. The real magic happens when you let Tsuchimoto, his crew, and the victims guide you through lives lived under the too-safely compartmentalized banner of "TRAGEDY."

My first of his films, however, was The Minamata Mural, a rare title that I encountered through tenuous connections to the library systems of NYU and Columbia. NYU had this giant CD collection of Toru Takemitsu's film score work, and as a huge Takemitsu fan I worked to hunt down the [film] titles I didn't know. Columbia had some huge DVD collection which included an unsubtitled transfer of The Minamata Mural [which Takemitsu scored]. The film was so beautiful that I made it a personal project to get it translated on the cheap and see if anyone wanted to show it. Tom Vick at the Smithsonian's Freer Gallery was into the idea, and we showed the film in 2019 there and then at UnionDocs on a 16mm print. (Thanks to Kelly Li for that translation!)

I had by then seen Victims, but I focus on this experience with Minamata Mural because it revealed to me that Tsuchimoto was a major talent whose deep cuts were potentially as exceptional as his renowned works.

EG: How did this experience lead to you programming this significant retrospective?

MC: After delving further into Tsuchimoto's filmography, and after a year-plus of talks with curator Ricardo Matos Cabo [of Open City Documentary Festival] and Sakiko Yamagami of Siglo Films (the Tokyo company that holds most of the rights and prints of Tsuchimoto's work), I felt encouraged and steadfast about screening these films in the US. It's an expensive retrospective, given the amount of translations needed and the high percentage of works screening on film. Only one feature will not be on film, though even that will show as an entirely new print scan. It is invaluable that we at the Museum have been able to share some of the shipping costs with the Open City Documentary Festival in London, who just screened their version of this retrospective this September.

EG: It’s interesting that you saw a deep cut like Minamata Mural first. Tsuchimoto films Iri and Toshi Maruki, and how their art is changed by the experience of depicting the victims. It might be the first of the Minamata films where he puts himself directly in dialogue with other artists who represented the victims, not just the Marukis but also the writer Michiko Ishimure, whose poems and essays about Minamata helped bring national attention to it.

MC: As you shrewdly pick up on, The Minamata Mural functions, in a way, as two films. The first film documents the painting and presentation of the murals, the second shows the Marukis interacting with the children of Minamata and reflecting on the power and limitations of their artistic gestures. Tsuchimoto saw this as a prime opportunity to dialogue with his own career as an artist working in the shadow of tragedy. That said, The Minamata Mural, during the painting segments, gives itself completely to the Marukis' lives and their creative process.

EG: He maps out his own trajectory toward filming the Minamata community through the Marukis—going from a confrontational style, wading into the middle of direct-action protests in Victims, to the later movies where he focuses less on people’s indignity and suffering and more on how they simply continue to live their lives.

MC: Tsuchimoto was in a contemplative mood in the 1980s, which bears out just as strongly in Umitori, [which would seem like] a small film on paper, whose subjects are given room to breathe it into a work of major heft. I was recently talking to Ricardo about how Minamata Mural and Umitori are the keys to understanding Tsuchimoto's whole M.O. as a filmmaker. Neither is particularly demanding, and you can choose to let each one wash over you or engage a bit with how Tsuchimoto and his collaborators take in their surroundings and interact with people. In [the latter] case, both films sing a song of quiet immensity that feels rare and inspiring.

The original title for this series was going to be "Noriaki Tsuchimoto and the Original Sin of Documentary Cinema," and I had cribbed this “original sin” talk directly from Kazuhiro Soda's translation of Tsuchimoto's writings on The Minamata Mural. The original sin of documentary, so to speak, is that filmmakers almost always benefit more from films than their subjects do. Perhaps the main reason we ditched this title is that reminding audiences of this fact isn't necessarily the best marketing angle for a series about a markedly humanistic director. But that's Tsuchimoto for you: he's unflashy and he interrogates the limitations of his own project, and he made an incredible body of work that's tough to market for these same reasons.

EG: There’s this remarkable, very long extended sequence in the middle of Mural where the camera moves around the finished murals, reframing different parts of them. It reminded me of the ending of Andrei Rublev (1966). What do you think compelled Tsuchimoto to shoot that sequence, which is quite distinguished in style and content from scenes in the other Minamata features?

MC: The mural close-up sequence is extraordinary, and definitely Rublev-esque. I would be surprised if Tsuchimoto had not seen the Tarkovsky. It's more than twice as long as the sequence in Rublev. It's smack-dab in the middle of a film whose title and narrative momentum would seem to be building to finish on this detailed display of the completed murals, rather than have it serve as a half-way bookend.

It's a curious product of Tsuchimoto coming into a project with greater-than-normal resources: for The Minamata Mural, Tsuchimoto was working with color 35mm stock, more expensive than his usual 16mm, and was collaborating for the only time with Takemitsu, who scores the mural sequence with a tone-cluster-stuffed ocean of strings. Due to the expense of the production, Tsuchimoto and his crew ended up using a very high percentage of what they shot, which makes it all the more compelling that he chose to stitch together twenty minutes of zooms and pans and textural close-ups of a primarily black-and-white mural shot on color film stock.

EG: The retrospective title you originally proposed is a good segue into talking about how Tsuchimoto interacted with his subjects. He’s filming people with severe disabilities who can't speak for themselves, and in situations where consent can’t be clearly secured. In contrast to Tsuchimoto is someone like Frederick Wiseman, who in films like Hospital (1970), Blind (1987), and Deaf (1986), tends to take the position of someone who is “just looking.” But Tsuchimoto gets into territory that most filmmakers wouldn’t go out of fear of causing harm. He’s not thinking solely in terms of helping or harming one’s subjects, which is already a paternalistic stance. Instead, he’s trying to construct relationships with the camera which give these “victims” the space to express their own agency.

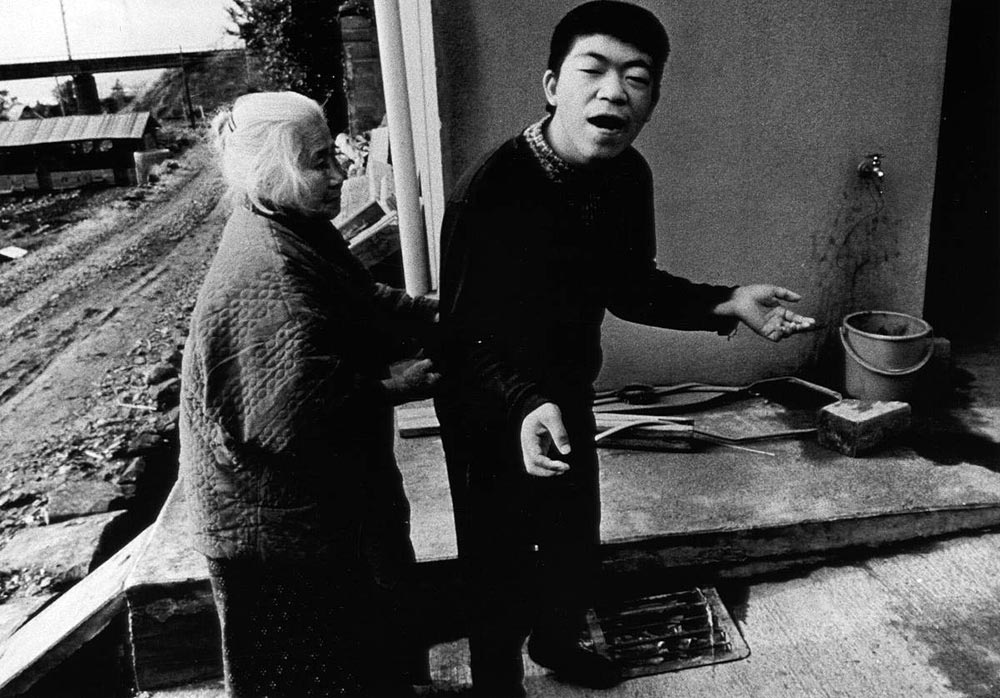

In The Shiranui Sea, there’s this scene of an older Minamata victim showing a teenaged victim the modified car he’s learned to drive. In this film where most of the interactions disabled people have are with their abled caretakers, it’s a moment where a group of disabled people are in community with each other. It shows the spectrum of severity of the disease, how differently it can manifest. It destroys the monolithic image of Minamata sufferers the public had at the time. And it’s a small moment of freedom, or even just the promise of freedom, within this very institutionalized structure of a rehabilitation center. Is there another scene that stands out to you where Tsuchimoto shows this process of building relationships through film?

MC: The Shiranui Sea is chock-full of incredible moments. You've already mentioned the hand-operated car scene, but two other scenes stand out to me as particularly poignant. There is the in-home interview with Tamotsu Watanabe, who is home-bound by a relatively mild—though still debilitating—case of Minamata disease and has used his payout from Chisso to build a beautiful house and buy himself cameras and toys. It's a predicament that briefly flips the film on its head. Here's a man who seemingly has everything people would want, and yet what he longs for is to be able to work with joy as a fisherman again. Tsuchimoto allows him ample space to remark on the peculiarity of life as a whole—life's essence made clearer by disability.

The other scene involves a neurologist, Dr. Harada, discussing with a well-spoken Minamata patient her not-great prognosis. At one point, after he asks "Any other questions?," she breaks down sobbing and exclaims, "I don't know what to do!" It's absolutely heartrending, but also eminently real, and Tsuchimoto keeps on the scene and the conversation long enough that some radical kernels of wisdom about life come sharply into focus. In specific cases, disability combined with government support creates an existence that on the one hand feels undignified and invisible, and on the other hand persists uniquely outside normal paradigms of lived experience.

EG: I wonder if you think that Tsuchimoto succeeded in expressing the subjectivity of the people he was filming, or if he was still projecting his own thoughts onto them. Certainly the distinction between the two is not clear-cut.

MC: I don't think I can answer the question without falling into a feedback loop: Tsuchimoto was certainly always aware of the dichotomy between being conscious of what he himself was bringing to a film, versus giving said film over to its subjects. He was doing his best to asymptotically gesture at that unreachable ideal of giving a film fully to its subjects. His films aren't far from being simply well-done vérité cinema, by someone with a big heart.

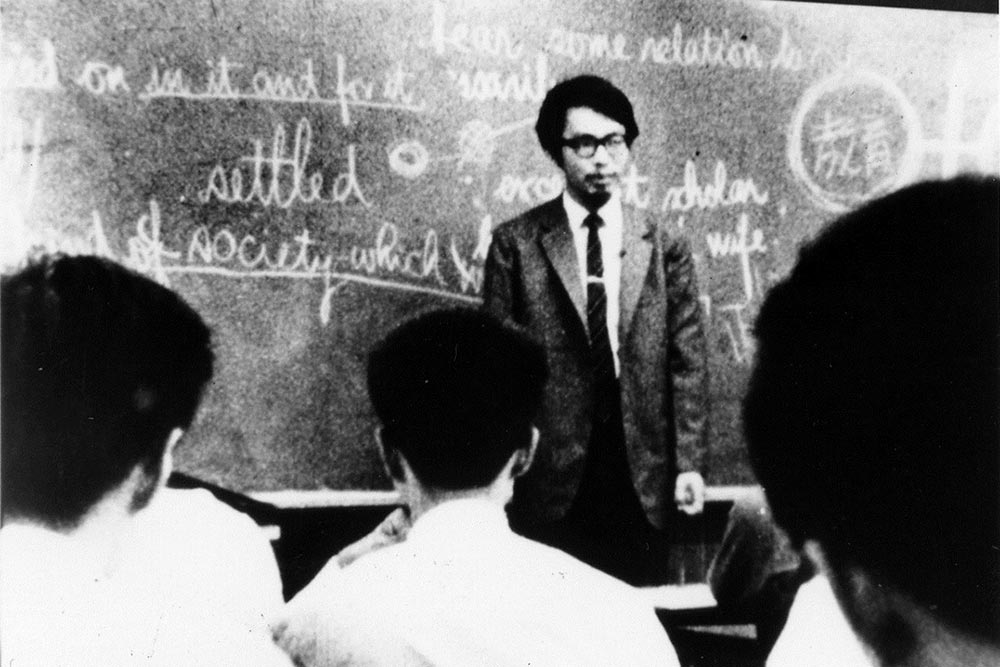

The development of vérité—or something similar to it—in Japanese documentary cinema is a fascinating and underexplored historical parallel to its "start" in the Western Hemisphere. I can't pretend that I'm an expert on this, but I know that Tsuchimoto gained his chops at the industrial film production company Iwanami, under the tutelage of such mentors as Susumu Hani and [alongside] peers like Shinsuke Ogawa.

EG: It is fittingly ironic that Tsuchimoto started out making films at a PR firm like Iwanami, designed to communicate to stockholders on behalf of these large corporations, and then began a career where he did the exact opposite, using what he learned to attack those systems. You have a few selections from that period in the program: On The Road (1964) and Tokyo Metropolis (1962). The latter film was made for a TV program, Discovering Japan. Why are these commissioned films included in a Tsuchimoto retrospective?

MC: The early films of Tsuchimoto, especially those funded by Iwanami and commissions [like] Tokyo Metropolis and On the Road, are glimpses into a subversive young filmmaker. On the Road is one of Tsuchimoto's most staggering accomplishments. There is always a critical energy of political engagement in Tsuchimoto's work, even if his means of expressing this and his aims shifted over time.

The simple answer [as to why they’re included] is because they are great. But it seems what you're really asking is whether I can speak to any stylistic or ethical threads across his filmography. I can certainly make connections between [cinematographer] Tatsuo Suzuki's exploratory panning shots in On the Road and Koshiro Otsu's panning shots that are used to establish a sense of place in films like The Shiranui Sea. And I can certainly make connections between the subversion of the TV program Discovering Japan, [through] showing that Tokyo youth cannot afford basic necessities, or the subversion of the Tokyo Police and, say, the demonization of the Chisso Corporation in the Minamata films.

EG: You are also screening Prehistory of the Partisans (1969), which was made with Shinsuke Ogawa’s production company, Ogawa Pro. Though they both made films together, Tsuchimoto drifted away from Ogawa’s very devoted and militant approach to living in the reality of his subjects, which caused a lot of internal strife in the company. As you’ve pointed out, the fact that Tsuchimoto was aware he had no first-hand experience of living with Minamata disease certainly contributed to this reevaluation.

There’s an interview with Koshiro Otsu, who worked as cinematographer for them both, where he mentions the differences in their styles. For example, Ogawa would use narration to insert himself into the film whereas Tsuchimoto would go in front of the camera more often. Though he was never “in the weeds” in the way Ogawa was, it strikes me as a different kind of immersion in the world—in the space created by a film production more so than daily life.

MC: When Tsuchimoto made Prehistory of the Partisans and Minamata: The Victims and Their World, he was working much more like Ogawa insofar as he was fully enmeshing himself in the communities of those films. The intense Ogawa way of doing things is pretty aligned with Tsuchimoto in the beginning, and both directors are further connected by being forced to carve independent film lives outside of mainstream funding streams. I think Tsuchimoto took a path of less resistance down the line by simply embracing a frankness about the taintedness of being an intrusive outsider.

EG: Tsuchimoto is so multifaceted, yet most discussions of his films rarely extend beyond the Minamata series. Is there anything you’d want people to know about Tsuchimoto that we haven’t already covered, here or in your program notes?

MC: Sure, I have lots. A director like Tsuchimoto is bound to always be wrapped in a context of solemnity and achingly-earnest discourses about “doc ethics”. It's unavoidable; that's just how historicizing and marketing work. I feel this does a disservice to one of the things that attracted me to Tsuchimoto in the first place: his great and adventurous taste in music and musical collaborators. [There’s] his use of jazz, especially Thelonious Monk, in Tokyo Metropolis, his really incredible scores from Takemitsu in The Minamata Mural, from Teizo Matsumura in The Shiranui Sea (which also features guitar work from the relatively obscure composer Takayuki Oguri), Riichiro Manabe in Minamata Revolt: A People’s Quest for Life (1973), Minoru Miki in On the Road and The World of the Siberians, and Midori Takada in Afghan Spring. There’s also the fact that My Town, My Youth (1978) is built around [young Minamata victims] organizing a Sayuri Ishikawa benefit concert. I am immediately ten times more endeared to any filmmaker whose musical or aural sensibilities speak to me, and so it was with Tsuchimoto in a big way.

The other thing that I don't think will ever properly receive much notice is Tsuchimoto's wry sense of humor. It creeps in more and more through his career. I'm thinking of the workers chanting a song about wives' farting holes in Shiranui Sea; I'm thinking of the curious man who held out and never sold away his fishing rights in Umitori. It's not that he's got as many silly sequences as, say, Wiseman, but Tsuchimoto still subverts what one would expect from his solemn and serious reputation in a way that feels light, wise, and always adventurous.

Taken as a whole, his filmography makes manifest that he was tirelessly bumping up against the limits of what one can do with art and communication. None of this would be interesting to point out if I didn't feel that his films reveal and bend these “art limits” in unpredictable ways. The journey that takes Tsuchimoto from making On the Road to making Umitori is no less radical and full of mysterious revelation than the journey that took Jarman from Sebastiane (1976) to Blue (1993). I can't succinctly put this sense of revelation into writing, but I can say that it has heretofore been a rarefied circle that has experienced it through Tsuchimoto's work. I'd like to see that circle ripple outward through international film culture.

The Noriaki Tsuchimoto retrospective runs November 12–27 at the Museum of the Moving Image, with most films screening on rare archival prints.