By 1978, the New Hollywood revolution was cooling into its brushed aluminum entertainment phase. For some of the so-called “Movie Brats,” this transition would cement their fortune, and leave others in a state of perpetual re-adaptation—or worse. In hindsight, John Milius’s Big Wednesday is an expression, not just of generational growing pains, but of the growing pains in Hollywood itself, that would soon bring the contradictions between authenticity and commerce to a reckoning point.

Milius polishes his loosely autobiographical surf film with nostalgia like so much paraffin wax. It’s populated with uncomplicated, pretty young people; their lives structured around bonfires and beer toasts and the kinds of set-pieces designed to keep a viewer’s own memories company. Milius’s portrait of an early ‘60s beach community modeled on his own Malibu youth is also pocked with eruptions of melancholy and violence that strain for an emotional truth, one told not through realism, but through the contesting forces of melodrama.

From the moment his central trio first descends through the ruined beachside stairway, Milius is forging connections between their rising and falling fortunes and the eternal seesaw current of the Pacific Ocean. For Matt, Jack, and Leroy (a.k.a. “The Masochist”), surfing is a social wellspring and an allegory of their roots—to their “spot” on the beach, as well as to their sleepy, working-class suburban home. That home is itself oddly precarious, a sort of socio-economic cove both for and against the flow of external currents, with a conspicuous absence of paternal forces to hold things in place.

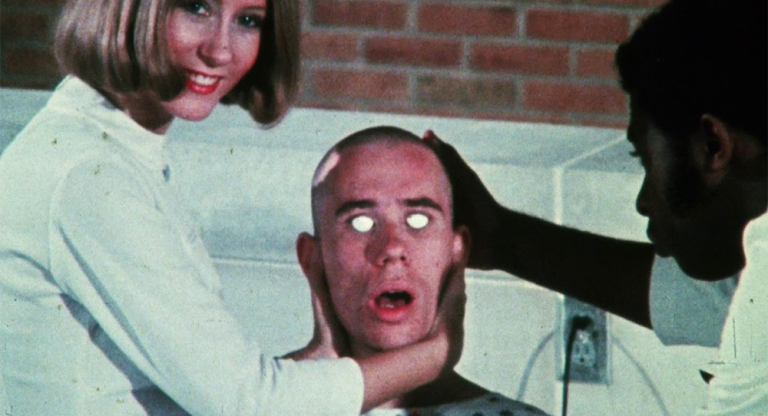

The trio’s dynamic tensions send them spinning apart at the emergence of the draft. In an intake sequence that rivals the one in Full Metal Jacket (1987) for its sheer tonal weirdness, Leroy and Matt play their phony injuries and insanity for laughs, while Jack embraces the forces of change and accepts the responsibilities of a world beyond the beach. Chronic asthma kept Milius himself from enlisting as a Marine, but despite his infamous political conservatism (manifest here as a kind of white libertarian chauvinism) his treatment of the war is as another event in the disintegration of the community’s idyll, one which scatters and extinguishes young lives, and leaves its larger meaning unclear.

We may question at length whether these characters merit the Wagnerian aura that clings to them—intermittently, though, Big Wednesday has the nimbleness to turn this question back on us. Is heroism anything more or less than an instant caught in the curl? As the trio carry their wounded brother out of the water again after the final catharsis—and, presumably, the impending onset of andropause—one inevitably thinks of Milius’s two real-life friends, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. At the peak of their productive friendship, the three directors traded percentage points from each of the films they released over this 12-month stretch: the other two films were Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Star Wars (1977). Meanwhile, per Quentin Tarantino, Big Wednesday’s fate would be as one of the most requested rentals on Manhattan Beach for which no video release existed. Big Wednesday’s commercial failure was another harbinger of New Hollywood’s closing frontier, but Milius got the message: his next effort would be Conan the Barbarian (1982).

Big Wednesday screens tomorrow afternoon, June 1, at Anthology Film Archives on 35mm as part of the series “Foreman’s Favorites.”