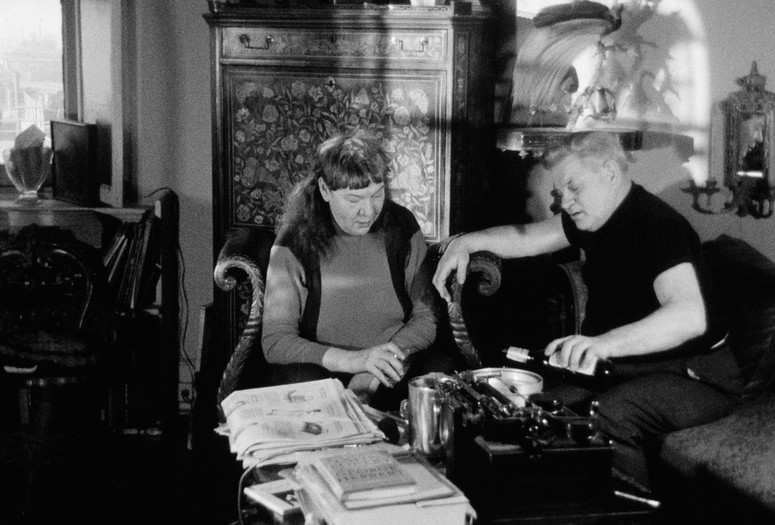

On Sunday, April 4, 1965, Andy Warhol and his crew loaded 16mm equipment into a station wagon and headed down to Brooklyn Heights for the day, to make a movie. They had no screenplay; just a concept that promised cinematic fireworks. They were heading to the Montague Street penthouse apartment of Marie Menken and Willard Maas, the bohemian couple known among friends for their weekend-long drinking bouts, which invariably led to raucous yelling matches between the pair. Kenneth Anger, one of the many filmmakers, poets, artists, and playwrights who regularly hung out at the apartment, said, “watching their arguments was a little like watching Punch and Judy.” Menken and Maas were reportedly the inspiration for George and Martha, the main characters in Edward Albee’s groundbreaking and acclaimed 1962 Broadway debut, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Warhol must have thought that his camera could capture a real-life version of the Albee play.

Just a month earlier, Menken gave a spirited performance as Fidel Castro’s sister in Warhol’s film The Life of Juanita Castro. Warhol was cranking out his feature-length films at a remarkably rapid rate; Juanita Castro was filmed on March 13 or 14, and it premiered on March 22. Warhol’s method was to film two 33-minute reels, with sound recorded directly onto the film. He would splice the reels together without editing, and release a 66-minute feature. This modus operandi drew surprising praise from Andrew Sarris, who wrote, “Warhol’s ideas on direction are simple to the point of idiocy—or genius. He puts the camera on a tripod, and it starts turning, sucking in reality like a vacuum cleaner.”

By the time the camera started rolling that Sunday in Menken and Maas’s cramped living room, both of the stars were clearly drunk. And without a script, they were at a loss as to how they were supposed to perform. Their attempts to argue fizzled into incoherent rambling, and stabs at humor fell flat. Menken seemed bored, and Maas was mainly focused on the drinks he was pouring himself.

After about twenty minutes of continuous filming, Warhol begins to send other people in front of the camera; first is John Hawkins, a young boyfriend of the bisexual Maas. Hawkins starts caressing and kissing Maas; their physical play continues through the film. He is followed by the poet and frequent Warhol collaborator Gerard Malanga, who takes a place on the floor, at Menken’s feet. And then—in her first screen appearance—the incomparable Edie Sedgwick sits next to Malanga. After a break between reels, the playwright Ronald Tavel joins the scene. According to Tavel, “When the second part got off to a wobbly start, Andy bit his upper lip and turned to me and asked, ‘You want to step in?’. I do so and sit on the back of Marie’s chair and hold her hands comfortingly for most of the reel. We whisper together and she kisses me a lot.”

The action becomes cacophonous; multiple conversations are taking place on screen, and the performers are also talking with the off-screen crew. Menken tries a few conversational gambits, first describing a funeral she had just gone to in Flatbush, musing about death, and then sharing a story about pulling a knife on a young man on a subway car who had been threatening her. These stories don’t really lead anywhere; eventually (and humorously), Menken creates some excitement by starting to scream. When the filming ended, Malanga reportedly told Warhol that it “was great.” Warhol, according to Ron Tavel, stared ahead and simply said, “No, it’s not.” Unhappy with the results of his Sunday expedition, Warhol abandoned the film. No prints were ever made, and in the 58 years since it was produced the film has never been shown to the public.

That is, until tonight’s screening at the Museum of Modern Art, as part of a truly mind-boggling program that pairs the Warhol film with a pristine 35mm Academy restoration print of Mike Nichols’s film adaptation of Virginia Woolf, and includes a panel discussion with Malanga, now 80; Philip Gefter, author of a new book about Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?; Mark Harris, Nichols’s biographer; and Greg Pierce, director of film at the Andy Warhol Museum. Here is the world premiere of a film that Warhol never wanted to show publicly.

Warhol’s disdain for the project aside, Bitch is an absorbing film whose energy and interest comes from the multiple layers on which it operates simultaneously. It is a meta-film. Menken’s first line—in what is either mock confusion or genuinely drunk disorientation—is “Where’s Andy; he’s supposed to shoot a film tonight?” There are frequent references to Warhol, to the camera and sound recording equipment, and to the offscreen crew. Both Maas and his boyfriend are constantly urging Menken to perform for the camera, and they joke about whether or not the camera is running.

The film also works as pure cinéma vérité, an intimate and revealing slice of life. We focus not on any superficial scripted drama but on the human interactions; the frame is charged with moments of sexual tension, tenderness, resentment, frustration, shyness, and posturing. Maas goads Menken a few times, asking her aggressively when she’s going to make her next film, and proclaiming, “Marie is famous, only in the Village Voice.” As Menken tolerates Maas’s groping of Jack Hawkins, she also turns her amorous attention to Tavel, who stands behind her. (In a journal, Tavel explains that he was at the apartment just to deliver a script to Warhol: “When the second part got off to a wobbly start, Andy asked me if I wanted to step in.”). Meanwhile, Malanga gets cuddly with Sedgwick, while she divides her attention between him, Chuck Wein (her boyfriend, off screen), and the two sound recordists. There is plenty of drama to observe, and with such a chaotic frame, the viewer is free to scan freely, as in a film by Robert Altman or Jacques Tati.

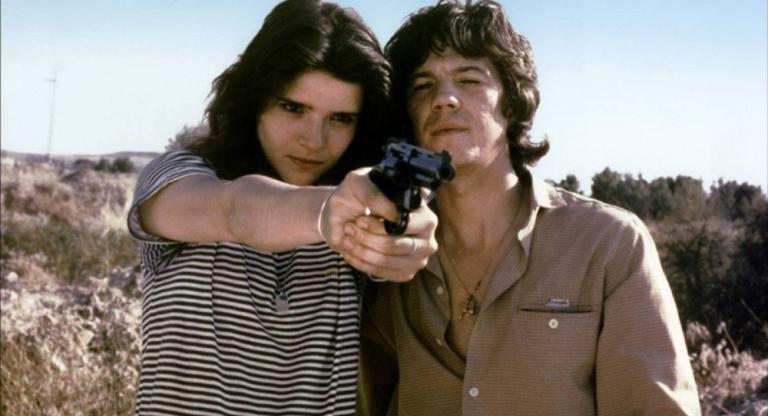

The spontaneity that the film records brings up another fascinating tension: that between the artificial nature of staged theater and the more authentic theater of real life. The most dramatic moment in the film—and the one that gives Bitch its title—comes toward the end and is sparked by Sedgwick, who has by this point taken over the movie. Malanga has been telling the increasingly gregarious Hawkins to calm down and stop talking. Finally, Edie stands up, takes a few steps, and spits on him. In shock, he exclaims “You’re a female dog.”

Edie’s beauty, charisma, and quirky energy are all evident in Bitch, and her rise to Warhol superstardom on the heels of the film was almost instantaneous. Exactly a week after Bitch was filmed, Warhol filmed Poor Little Rich Girl, a solo film of Edie waking up, talking on the phone, and getting dressed. Famously, reel one of the movie is out of focus; Warhol bought a new lens for his camera and filmed another reel, in focus, the following weekend. The film premiered on April 26, to a rave Village Voice review from Jonas Mekas, and Sedgwick starred in nearly all of Warhol’s films that year.

“Andy Warhol’s Bitch and Mike Nichols’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?: A Loaded Conversation takes place this afternoon, January 13, at the Museum of Modern Art, as part of the series “To Save and Project: The 20th MoMA Festival of Film Preservation.”