New German Cinema legend, social theorist, and Theodor Adorno's former legal advisor Alexander Kluge was in town for a busy weekend, reading poetry at the Goethe Institute and introducing several screenings at Anthology Film Archives. Tonight is your last chance to catch him before he flies back to Germany, as he'll be at MoMA to guide us through a thematically arranged program of short films. Yesterday his packed schedule had a half-hour blank in it, so I sat down with him at the Goethe Institute for the following conversation.

The misfortune of Doge Foscari. I DUE FOSCARI, Giuseppe Verdi, after a libretto by Lord Byron. “That I have to kill that which I most love” (2016)

Cosmo Bjorkenheim: You’ve said that cinema is where realistic and anti-realistic attitudes meet, a clash of facts and dreams, of the way things are and the way things could be. Nowadays, when millions of people are using cameras primarily to document, archive, and broadcast their lives, has the utopian dimension of cinema started to vanish?

Alexander Kluge: It’s a difficult question. First, it’s not a capacity of cinema alone to be antagonistic and to have “antirealism” and realism. Every human being functions like a camera to some extent. You have wishes, you have hopes—you have, at the origin, libido, and libido is constituted by a disappointment. The baby thinks only of lust: “Everything belongs to me.” Nothing but my lust, my body, my senses, and so on, and this is disappointed, of course, by the reality principle. Reality educates the child. The primary trauma produces two separate kinds of perception, of mind, of the senses, and of libido—two constitutions of the subject. This subject is always divided in two. Auden says, for instance, “Denn Nichts kann eins und alles sein, Ein Riss hat es getrennt.” Socialist Realism for instance does not see this constitution of subjectivity. It’s not my will to be antagonistic, it’s my constitution, I function like this. And if I deny it, the partisans within me will denounce what I do. So lust invented art—like cinema—and made a technical addition to this general constitution of the human mind.

Now, I admire the Internet. Everybody can be a radio station. This is the idol of Bert Brecht’s “radio theory.” And I think this is something new, revolutionary, and rich. On one hand, it seduces. It's the “new sirens”: the media, advertisements, the world of commodities. Every commodity is propaganda for itself—it’s a conjuror, a sorcerer—and all this is persuading the libido to come over. It’s not that you take something in from the media; rather, they pull something out of you. The government does, Google does, Amazon does. All people are capable of documenting, but they don’t document. On Facebook, for instance, they don’t give the whole of their soul.

CB: Do they make a commodity out of a part of their soul, to sell?

AK: To some extent. Not a commodity you can buy for money, but that you can buy for acknowledgement.

CB: Is acknowledgement a new form of currency?

AK: Right. It always has been. In love, rivalry between males has always been a currency, but now it’s a generalized, global currency, and a very important one. To be proud of oneself one needs the acknowledgement of others, and therefore you notice that most people put onto the Internet—into the social media—what they think would be a virtue in the eyes of others. I am the actor of my idols, not my identity. You have to concentrate on yourself to form an identity, and then you need discussion with a certain other to have an identity.

CB: Instead of with a generalized other?

AK: You could, but you cannot talk with a generalized other because you are not a generalized me. You’re a personal me, and therefore you need a personal other first, to form and stabilize your identity. Afterwards you can communicate with a globalized other, but it’s very difficult. To put it briefly: from the first moment, this inflation of silicon created a desert. But oases are possible. The desert, as we know, is very vivid, but one should study the vivid parts of the desert and not the barren parts. So you have a new antagonism: not the antagonism of “antirealism” in cinema fighting with reality, with documentary, but something else which cannot distinguish between what is a document and what is fiction. You get lots of hybrids.

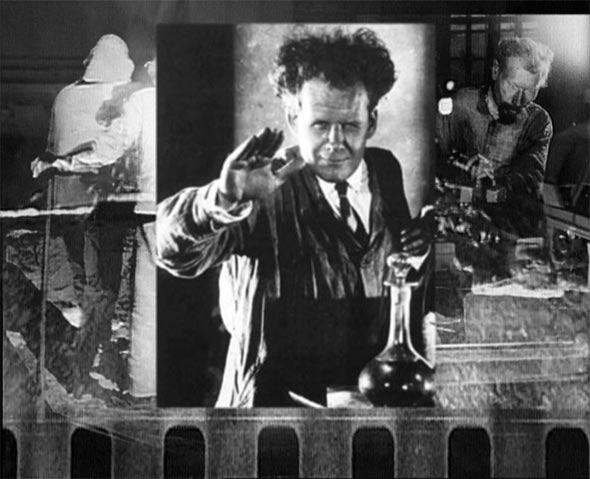

Sergei Eisenstein in Nachrichten aus der ideologischen Antike (2008)

CB: When you made Nachrichten aus der ideologischen Antike (2008), were you tempted to make Eisenstein's film adaptation of Capital yourself, basing your version on his notes? Why did you decide to make a documentary about it instead?

AK: I would love to, yes. But you see, he’s really a master. He also has a naïveté that I don’t have. I would be very cautious. To some extent what he made were masterpieces, and to some extent it was propaganda. Some parts of October and Battleship Potemkin I would do in a different way. You would see in this film, for instance, Tristan and Isolde with the sailors of the battleship Potemkin: revolutionaries and love in one net of narration. Schroeter invented that. I would try to find a kaleidoscope, a prism, the eye of a dragonfly instead of a homogeneous film. So I would give hints. I would not make a film about a laborer couple, a man and a woman, and pretend that the whole history of mankind can be contained in one day between two people. Even James Joyce, who was supposed to write the script, would have denied that this is possible. He never said that you can understand the world. This is the Russian Revolution, you see—I admire it, but this is utopian. I love heterotopias, but not utopias.

We're making a ten-hour film next year about the centennial of the Russian Revolution and covering only the first five years. It's like a fly in amber. We archaeologists, as narrators, we try to find this fly, and with the Russian Revolution you can find it. You find, for instance, the homo novus , the new type of child. They wrote children's books. Osip Mandelstam, Khlebnikov, Kharms, Mayakovsky—they all made beautiful poems for the New Child, to bring literacy to Siberia. And while they were introducing electricity, they looked at the stars from the beginning onwards. Alexander Bogdanov for instance, the hero who led the Proletkult movement, he wrote a book about Mars already before the Revolution. Marx the planet: it’s a very interesting subject. I would like to make a film, “Marx the Planet.” Might be possible, you see? If they had conquered a planet they would have, perhaps, called it “Marx.”

CB: And this would have been a site to build a socialist utopia ex nihilo?

AK: Ex nihilo , but the nihilo is a vacuum, and the vacuum has a potency. To form a new Mankind is, of course, possible, but it needs five hundred years, or perhaps a thousand years. But capitalism also needed four hundred years to establish. The agrarian revolution took four thousand years. We have to be patient. Utopia becomes better and better the longer we wait for it.

CB: Is the new man, the homo novus, more perceptive? Do they pay closer attention to the world? There’s a Wallace Stevens quote that you mention in Nachrichten aus der ideologischen Antike: “Communism is an instrument to improve men’s attention.”

AK: Yes, according to the early Marx. It’s not the opinion of the Party. The Communist Party would deny that. But in reality, if ever something like communism would exist, solidarity could exist, a homo novus could be developed. Then attention, Aufmerksamkeit , would be one of the capacities. But this Aufmerksamkeit is a focus of great variations, a plurality of senses, feelings. We have five senses by nature and 66 by society. If you are single-minded, your whole will fixed on one point, then you are a good Nazi. If you push the power of your will down, then you have polyphonic structures.

CB: Polyophonic attention?

AK: This polyphonic attention is the eye of the dragonfly.

CB: Is it an openness to distraction?

AK: Of course! Benjamin describes it as an openness to distraction, which is concentrated. Both. As you are capable of being distracted, you are capable of concentration. It’s practical dialectics.

CB: Concentrated distraction is practical dialectics?

AK: Yes. If you concentrate you are not distracted, and therefore you cannot be concentrated. You have only a pure will. And this pure will is blind.

CB: This is a question I’ve wanted to ask you for a long time: what were people’s dreams like before movies? Did they follow verbal associations, like poetry? Were they theatrical? Were they more like novels?

AK: I think they're under the lava of the pictures of mass industry, like a volcano that produces lava onto Herculaneum and Pompeii and down below there’s a city. I think we lost dreams by cinema.

The Eiffel Tower, King Kong, and the White Woman (1988)

CB: Cinema replaced dreams?

AK: Mainly commercial cinema, intentional cinema. It tries to organize reality to a certain scheme. Very seductive. If you take Hitchcock, a master—you see, I admire his technique—but he’s a criminal as an artist because he subdues everything to the main interest. And the main interest, the rhythm of suspense, destroys everything beside it, the way an Autobahn destroys all small roads or paths in the woods. This has nothing to do with cinema. Cinema makes the senses more rich, but commercial cinema concentrates them in the capitalist sense. The generalized interest is the dictatorship of the probable. A good Hitchcock film has meaning, but never observation. You don’t find real people in danger who do with their faces what actors do in a Hitchcock film.

CB: Until they’ve seen a Hitchcock film.

AK: If somebody has never seen a Hitchcock film, he will have the face of a human being. It’s very improbable the way it looks when something happens. If a lion jumps onto a young lady in Ethiopia, she will have something on her face. But it does not look like in film, I’m sure.

CB: So Hitchcock’s cinema is a cinema of efficiency?

AK: That’s right, efficiency. Look, I’m not against Hitchcock, I took an example I admired. I myself am seduced by his films, and therefore he’s a master. I’m completely at the other end from Critical Theory, which would say, “No, it’s seductive.” But the sirens are also seductive, and we have to do something like what Odysseus did, but not bind ourselves. That’s our question. I’m interested in all improbabilities. The path to utopia, or to heterotopia, to auto-emancipation, goes improbable ways. Like the way we were formed. You sitting there: improbability an und für sich . The matter you are made of and that I’m made of and our earth is made of—just improbable. And that we’ve survived in evolution is completely improbable, that mankind did not perish and did not kill each other. Improbable. This is the contrary of films of the film industry. ■