CONTOURS is a column by Saffron Maeve examining films that thematize the world of visual art: heists, biopics, documentaries, and experimental fare. Maeve also programs a screening series of the same name and premise at Paradise Theatre in Toronto.

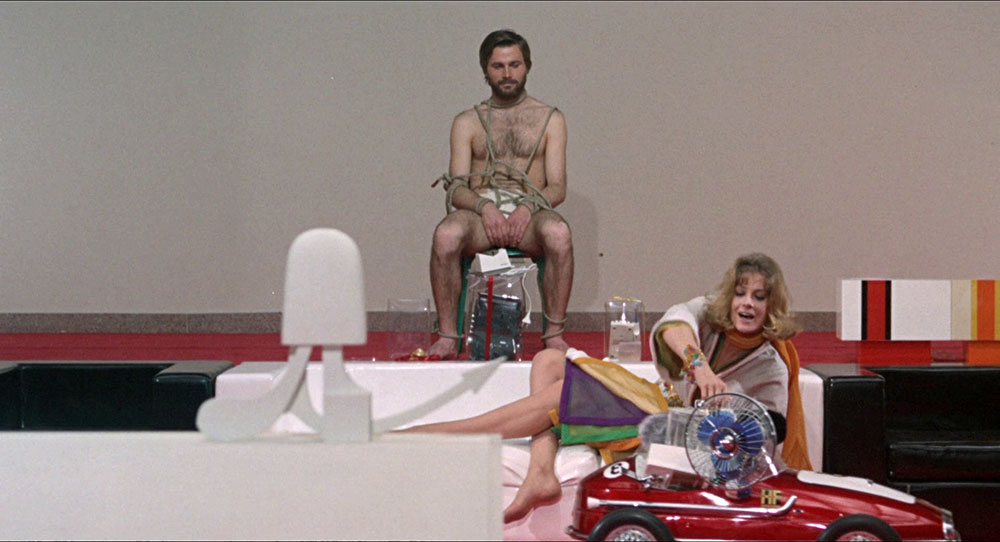

One of the stronger opening credit arrangements—a strobing series of paintings from varyious art movements: tonalist landscapes, fauvist portraiture, sacred scenes of the pre-Raphaelites, and newly commissioned works by pop artist Jim Dine; in them, portrayals of the pastoral, sensuality, torture, and worship. These high-speed figurations cut to a nightmare of a couple engaging in a sadomasochistic exercise: a man is tied to a chair, nearly nude, while a woman plugs in a host of electrical appliances at his feet. He wriggles as she describes them: toothbrush, “underwater television,” transistor refrigerator, knife sharpener, coffee grinder, juicer, shoe buffer, water pick, and toy car. The collective whirring sounds like screaming. He abruptly unknots himself and follows the woman into the bathroom with a knife, where she stabs his chest repeatedly.

Elio Petri’s slow-burning giallo A Quiet Place in the Country (1968) lays bare its artistic and theoretical aims in this early sequence: artistry as fetish, with the potential to haunt, pleasure, and penetrate, and as compulsion, a muscle to be flexed at any cost. The film is a loose adaptation of The Beckoning Fair One, a novella by Oliver Onions, in which a novelist retreats to an abandoned house in London to alleviate his writer’s block, but develops an obsession with an 18th-century spirit loitering around the property. In A Quiet Place in the Country, this locale is swapped for the Italian countryside and the central careerist is a painter, aptly called Leonardo (Franco Nero). Leonardo awakens from his nightmare to his girlfriend/agent Flavia (Vanessa Redgrave)—the woman from his dream—who encourages him to shake off his artistic slump.

Petri’s decision to change the central character from a writer to an artist is perhaps the film’s most intriguing gesture. Where the torment of the writer is relegated to the page or the mind, the plight of the painter is more visible, extending to the entire body. Leonardo is suffering from the bustle of central Milan; we see it in his restlessness, running around the city and acting on his every sexual compulsion. At home, he clicks through slides of misshapen breasts and war-torn cities, staring so intensely as though to force contrivance. He assaults a large canvas at first with brushes and paint rollers, then his bare hands in a frustrated attempt to knead significance into the work.

Even more absorbing than his failed paintings, though, is the host of bizarre, confrontational art objects scattered around Leonardo’s home at the film’s beginning: a steely, space-age chair featuring a replica of a human hand gripping a pistol between the legs; a towering, cubic enclosure caged with chicken wire and a white refrigerator at its center. Petri, also a prominent theater director, stages these objects as ancillary setpieces, which augment the film with context of Leonardo’s lack of consistent style and possible hackery.

A Quiet Place in the Country takes its first grand turn when Leonardo and Flavia retreat to the countryside, where he takes interest in fixing up a sprawling, dilapidated villa. Flavia is put off by the caving roof and shoddy flooring, but Leonardo becomes engulfed in the story of a girl, Wanda, who died on the property during an airstrike in the Second World War. The film takes its second turn as he shirks his artistic journey and collects information from locals, learning of Wanda’s reputation as a nymphomaniac, and begins to sense her spirit inhabiting the villa.

I am unfortunately susceptible to describing the tail-end of films as TÁR-esque in their last-gasp punishments. Though Todd Field did not originate this mode of stern scriptwriting, his depiction of an esteemed narcissist’s fall from grace seems to communicate a renunciation of celebrity and, in turn, a loss of imagined artfulness. And Petri’s comical wind-down of Leonardo as a limp De Sade figure is just that, 54 years prior.

A Quiet Place in the Country screens tonight at the Museum of Modern Art as part of their Ennio Morricone retrospective.